Support the Free Press | Facts matter. Truth matters. Journalism matters

Salt Lake City Weekly has been Utah's source of independent news and in-depth journalism since 1984. Donate today to ensure the legacy continues.

Buzz Blog

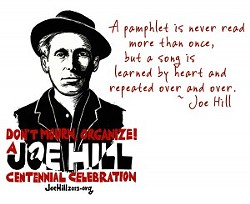

Executed a Century Ago by a Utah Firing Squad, Joe Hill to be Recognized

Free concerts, speeches and a request for a pardon

But it is in Utah where, this Saturday, Joe Hill will be remembered. For the past two years, the Joe Hill Organizing Committee has been hammering out the details of a celebration to recognize the 100-year mark of Joe Hill’s execution.

Musical acts including Judy Collins, Joe Jencks, and Anne Feeney will perform, as well as many others, in Sugar House Park, once the site of the Utah State Penitentiary where Hill was killed.

“There’s so much going on Saturday, I don’t know how we’ll survive it all,” says Ken Sanders, owner of Ken Sanders Rare Books, who helped organize the event. “I think it’s going to be really exciting.”

In addition to the performances, memorabilia and merchandise will be for sale, which Sanders concedes would be somewhat capitalistic if the proceeds weren’t going to cover the costs of paying the performers. The event, true to the spirit of Hill and the One Big Union he sang and organized for, is free.

Although efforts have been afoot for years to mark the anniversary, publicity surrounding Hill, who was convicted of murdering the grocer John Morrison and his son, Arling, reached a crescendo this week when The Salt Lake Tribune unleashed a comprehensive website detailing the murders, Hill’s legacy and the man’s sweeping impact on the labor movement.

All of the interest in Hill stems from two main veins: the first is that his execution propelled him to the upper echelon of the labor movement as its most revered martyr. The second flows from the belief by many 100 years ago, and far more today, that Hill was stone-cold innocent.

On the night of the murders, Hill arrived at a doctor’s office with a gunshot wound. Prior to being killed, Arling Morrison shot one of the people who robbed the family’s store, which was located at 778 S. West Temple.

Hill was swiftly arrested, tried and eventually executed despite pleas from world leaders, including American President Woodrow Wilson, to halt the killing.

It is a convenient, and perhaps true but nevertheless disputed narrative, that Hill, a Swedish emigrant who gained fame as a songwriter for the IWW, was pegged for the crime partly out of convenience and partly because of his union organizing efforts.

Hill maintained his innocence throughout the trial, but declined—for reasons that may never be fully known—to disclose his alibi. This alibi, according to historians like William M. Adler, who penned the most recent, and likely the most comprehensive account of Hill’s life and death, “The Man Who Never Died,” believe Hill was shot in a tussle over a woman.

During preparations for his book, Adler uncovered a letter from a woman, Hilda Erickson, who wrote that one of Hill’s friends, Otto Applequist, shot Hill in a fit of anger.

On the other hand, the Pulitzer Prize winning author and western historian, Wallace Stegner, believed Hill was guilty—a case he made in the biographical novel, “Joe Hill.”

Guilty or innocent, what occurred afterwards is not in dispute.

“It was the shot heard round the world,” Sanders says. “It set off labor riots in Moscow, Paris, Seattle.”

Hill’s songs, including “Casey Jones—the Union Scab,” “The Preacher and the Slave (Pie in the Sky),” and “There is Power in a Union,” have been sung, and continue be crooned, by some of the world’s most famous folk musicians.

For Sanders, it’s tough to talk about Hill, the IWW and the friction in the early 20th century between labor and capital as industrial modes of production enriched a ruling class, without talking about today.

Even though capitalism was the path America took forward, Sanders says the vast divide that continues to grow between the rich and poor in America makes Hill’s legacy all the more potent.

“If we thought the inequality of the gilded age was bad, let’s look at the 1 percent today and it’s far beyond that,” Sanders says, noting that Hill’s story and what he and the IWW stood for is “More vital. If we were at a crossroads then, we’re at a crisis now.”

In an effort to at last receive some state-sponsored recognition of Hill’s possible innocence, local attorney Clayton Simms on Wednesday filed a petition with the Utah Board of Pardons and Parole to Pardon Joe Hill.

Simms says a pardon, or any acknowledgement that Utah may have executed an innocent man, is a stretch, but a worthwhile endeavor.

“It does put the government in an uncomfortable position of having to admit it executed someone who was innocent,” Simms says.

Sanders says he tries to be cautious about speaking for what Hill may have been thinking a century ago, and for what the man might want said today. But he suspects a pardon—which acknowledges that prisoner is rehabilitated, not necessarily innocent—would not have placated Hill.

“He went to his grave, to his execution, without giving up the woman or whatever happened that night,” Sanders says. “If he wouldn’t do that, would he have accepted a pardon for something he didn’t do?”

In the lead up to, and during his trial, Hill’s refusal to testify in his defense was interpreted by some as guilt, and by others as the man’s belief that the justice system would surely not convict an innocent man.

“I think it’s pretty clear from evidence now that he had this alibi that he didn’t use and he just sort of relied on the fact that if you’re innocent, you’ll be proven not guilty, which has been proven not the right way to go about things,” Simms says.

Simms says he should hear back from the state in the next 40 to 60 days on a pardon, which would coincide with the actual date, Nov. 19, 1915, of Hill’s execution by firing squad.

And whether Hill would have wanted a pardon, a commutation, an admission by police that they were wrong or to be thrust into legend through martyrdom, no one can be sure. Simms, though, says a pardon, or acknowledgement by the state that it made a mistake, would be a good place to start.

“It’s a way to recognize that a mistake was made and it’s an attempt to correct it,” Simms says of a pardon. “Just because more needs to be done doesn’t mean you don’t take that step of pardoning him.”

More information about Joe Hill Day festivities is available here.