John Baxter did everything he could to get into the fight.

He volunteered for the Marines after high school. He signed on with a unit that was headed to Vietnam. He asked to go to the front. But the Corps had other plans for the 19-year-old West High School graduate from Rose Park.

“The technical term for it is REMF,” Baxter says with an amused snort. “A Rear-Echelon Mother—well, you know … I did what I could to get into harm’s way, but I spent my whole time in Saigon. I never got a Silver Star, and I never saved anyone’s life.”

He did get shot at. Mortars, rockets. Deadly things, though nothing landed too close. Still, you never know, so Baxter was a bit on edge when he returned home to Camp Pendleton in 1973. Walking past the artillery range one day, a short burst of gunfire sent him to his belly.

“Everybody else was just walking around, and I was down there on my stomach,” Baxter says. “It was a reflex, you know? In Vietnam, you do that because if you don’t do it, you could end up dead, but I still felt really silly lying there on the ground.”

That was the worst of it, though. The young Marine ended his military service pissed off that he hadn’t seen more action, but he’s since come to appreciate his good fortune.

“I’m not trying to recover from post-traumatic stress disorder,” he says. “I’m not suffering from the effects of Agent Orange.”

But every week he looks into the eyes of men who are. And it’s hard not to be humble.

Even in a judge’s robe.I Can Do That

Baxter may not have been wounded in the war, but he didn’t have a lot of direction in his life when he returned. He worked warehouses, unloaded hogs from railroad cars, spent time on an oil-exploration crew and lugged bricks as a mason’s assistant.

None of it paid well—and neither did his wife’s job as a teacher’s aid in the suburbs. When her Volkswagen broke down, they didn’t have the money to fix it, so she got a job as a receptionist at a downtown law firm, one she could walk to from their small apartment on Salt Lake City’s Capitol Hill.

That was the wake-up call.

As Baxter began to associate with the lawyers at his wife’s firm, he noticed something: They weren’t any smarter than he was—and they sure as hell didn’t work any harder. “And so, I thought, ‘I can do that,’” Baxter recalls. “I figured that I might as well do something that would make a bigger contribution and maybe be a bit more lucrative, too.”

He completed his undergraduate work at the University of Utah in 1989. Two years later, he began his studies at the Golden Gate University School of Law in San Francisco. When he graduated in 1994, he returned to Utah, where he found work as a public defender.

His clients were often alcoholics or drug abusers. Some were mentally ill.

And many, it stung to see, had also served in Vietnam.

In 2002, Baxter was appointed to the Salt Lake City Justice Court. Today, as part of his duties—and in no small part because of his dedication to his brothers and sisters in arms—he presides over the city’s veterans-court program.

It’s a role that has given Baxter plenty of opportunities for self-reflection. If the deck had been cut differently, the judge has often thought, he might be the one on the skids, and one of these men could be holding the gavel.

He considers this often as he tries to find the best kind of justice for his fellow vets. And he’s proud of what he’s been able to do for them.

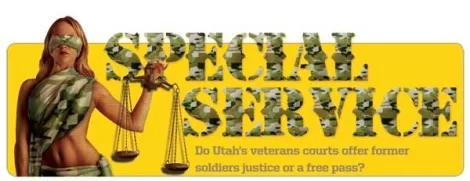

Still, some question whether the preferential treatment vets receive in courts like Baxter’s might amount to an unconstitutional inequality in the justice system.

And there is some evidence that the kid-glove treatment some defendants receive in veterans court only allows these troubled souls to continue offending—to the detriment of some and to the death of others.

Treatment Instead of Incarceration

The first court specifically for military veterans opened in Buffalo, N.Y., in 2008. Three years later, there are dozens spread across the country, at every level of the judicial system. Salt Lake City appears to be the only place in the nation, though, with vet courts at the municipal, district and federal levels. At each level, veterans carrying criminal charges—mostly nonviolent misdemeanors and lower felonies—are getting the opportunity for treatment instead of incarceration.

No one disputes that Baxter’s history in uniform was a key reason he was tapped to preside over the city court, but the truth is that he likely would have been the best candidate anyway. His specialty is specialty courts, which take cases in which defendants suffer from an underlying problem and in which there is reason to believe that they—and the community as a whole—would benefit from services directed toward solving that problem.

Salt Lake City has a handful of such courts, and Baxter is the man with the gavel in most of them, having presided over domestic-violence court, drug court and homeless court.

When he takes the bench at veterans court, Baxter doesn’t often ask the defendants about their experiences in uniform. If they wish to talk about the military-related factors that led them to his courtroom, he’s more than willing to listen. But the judge says he doesn’t like to pick at scabs, and he resists any temptation to put his undergraduate degree in psychology to any sort of diagnostic use.

“There are other people—better qualified people—to do that,” he says.

Baxter and his staff, along with the city prosecutor and public defenders, handle the criminal side of the house. Representatives from the Department of Veterans Affairs advise on the therapeutic progress of the defendants, carting in boxes of medical records and counseling reports that the judge can then use to make his decisions.

Among the program’s earliest customers was a chisel-jawed Marine named Jacob Hoard. He counts the court as one of the few lucky breaks he’s gotten since returning home from two combat tours of duty in Iraq.

"I'm Used to Being the Authority Figure"

It was well past midnight on New Year’s Day when Hoard realized that he’d screwed up. He and a few buddies had spent the past few hours at Trails Men’s Club in an alcohol-induced oblivion of the ticking clock.

Now they were sobering up—and realizing what trouble they were in.

“We weren’t supposed to be there,” Hoard says. “We were supposed to be at home, kissing our wives at midnight, and we needed to get our asses back to our houses.”

The Utah Highway Patrol had other ideas about where Hoard’s ass needed to be. The 27-year-old West Valley City resident hadn’t made it far from the club when the flashing lights of a trooper’s cruiser lit up the cab of the Kia Sportage he was driving.

The UHP was, of course, out in full force that night. In fact, a grant from the New Car Dealers of Utah had allowed the state to put more than 20 extra troopers on the road for the holiday. By the time the sun rose, UHP troopers had brought in 60 men and women for driving under the influence. It was still relatively early in the night when Hoard was pulled over, and, with apparently little else to do at the moment, several additional police cars were quick to arrive.

As Hoard recalls, it wasn’t long before a police helicopter was hovering overhead, too.

His heart was thumping. His hands were sweaty. His jaw tightened.

“I’m used to being in control,” he says. “I’m used to being the authority figure. Then I wasn’t, and I just lost my mind. I mean, all of a sudden there were 12 officers surrounding my car. Twelve officers? Why the fuck are there 12 of them?”

“That’s right, motherfuckers!” Hoard screamed. “Bring it all out for the veterans!”