Dave: How could this have not happened?

Andy: It just never happened. When I was young, tried, and it didn’t happen. And then I got older, and I got more and more nervous, because it hadn’t happened yet. And I got kind of weirded out about it. Then it really didn’t happen, and then … I don’t know, I just kind of stopped trying. —The 40 Year Old Virgin, by Judd Apatow

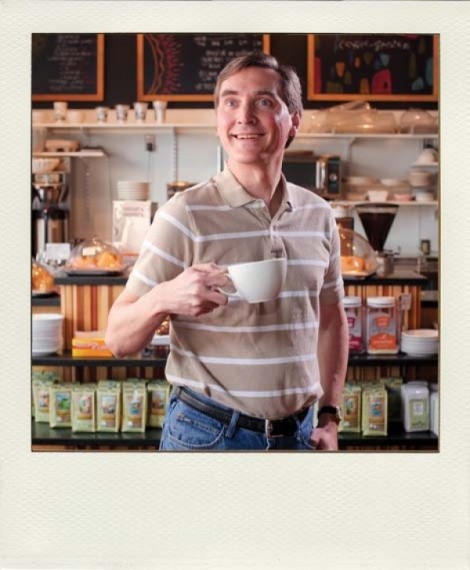

Four years of college. Graduate school. Early mornings. Occasional late nights. A time spent living in Seattle in the early ’90s, for God’s sake. Moving to a state where one’s consumption habits tend to serve as tribal markers. Fifteen years of marriage to a coffee drinker. All of this, over more than 40 years of my life, and somehow I never, ever, not once, drank a single sip of coffee.

There’s a societal presumption built into any kind of teetotaling, that it must be some kind of political, ethical or moral statement. But I neither adhere to the Word of Wisdom, nor have I staked out a position opposed to the impact on rain forests of coffee-bean farming. I don’t drink coffee because I never have drunk coffee. And I never have drunk coffee because … well, maybe it’s not all that complicated.

The easiest answer is that the circumstances that turn someone into a coffee-drinker never coalesced early in my life. I grew up in a household of non-coffee-drinking parents, so the habit was never one I assumed I’d follow. As a life-long “morning person,” I never required any particular chemical kick-start to allow me to function before noon. Hot drinks in general, including tea or cocoa, didn’t really appeal to me. My sheer general stubbornness made it something of a point of pride not to be doing what everyone around me tended to do—video games, skiing, tattoos, heroin—just because they tended to do it. And as I got older, it seemed to be one of those “acquired tastes” that would be more trouble—and expense—than it was worth to acquire.

I started to think that maybe I’d been missing something all these years. Coffee seemed to inspire cult-like devotion, and I was forever surrounded by folks for whom coffee defined communal interaction. It wasn’t just a beverage; it was a way of life. And I wondered if I could share that enthusiasm.

I would need guidance on such a perilous journey, a gentle hand to help me break my Cherry Mocha. Thus I would turn to baristas and purveyors of the rich, dark liquid to answer the question: Was there something out there that would change my perspective forever? Like a java-jazzed spin on Olivia Newton-John in Grease, maybe this coffee virgin could be turned into a coffee slut.

Historical Java

Certainly in Utah, coffee was a topic loaded with religious and cultural significance. The “Word of Wisdom” delivered by Joseph Smith in 1833—which stated, among other things, that “hot drinks are not for the body or the belly”—was originally a recommendation rather than a commandment. Smith’s brother, Hyrum, specifically clarified in 1842 that “hot drinks” included coffee, while Brigham Young in 1851 added the admonition “those who will not keep the Word of Wisdom, I will cut off from the Church.” Yet only a few years earlier, the westward-bound Mormon pioneers of the 1840s followed provisions guidelines commonly used at the time that recommended packing coffee for the journey. And it may have just been common sense, as worries about contaminated water supplies made a boiled-water beverage a wise choice—though the pioneers often allowed it to cool in an attempt to stay within the letter of the law.

Curiously, tainted water supplies also played a role in one of the most intriguing historical footnotes about coffee. Before coffee was introduced in Europe in the 17th century, the most common beverage with which an individual started his or her day would have been one that included alcohol. With plain water a breeding ground for contaminants and a general menace to public health, people often consumed weak beer or wine for breakfast, lunch and dinner. According to historian Tom Standage, quoted in the Joseph Priestly biography The Invention of Air, “Those who drank coffee instead of alcohol began the day alert and stimulated, rather than relaxed and mildly inebriated, and the quality and quantity of their work improved.” With thinkers beginning to meet in coffee houses to share ideas, the Enlightenment was born on the back of the coffee bean—which made it little wonder that European monarchs tended to shut down coffee houses whenever seditious or anti-authoritarian ideas began to percolate.

In colonial America, coffee became even more symbolic of the fight for freedom. In his coffee history Uncommon Grounds, journalist Mark Pendergrast describes how the colonial tea tax that gave rise to the 1773 Boston Tea Party also inspired “a patriotic American duty to avoid tea, and the coffeehouses profited as a result.” That included Boston’s Green Dragon coffeehouse and tavern, descried by Daniel Webster as “the headquarters of the Revolution.” Without coffee, we all might still be bowing to the Queen and calling elevators “lifts.”

But then there were the ethical and socio-political matters that gave a progressive-minded person pause. Coffee monoculture in Brazil, after all, played a significant role in the depletion of rain forest, as the developed world’s insatiable demand for coffee—and the coffee shrub’s three-year journey to maturity and tendency to deplete soil when grown in full sunlight—inspired more and more cutting to allow more and more planting. Activists fretted over how little of that $4 cup of coffee ended up in the pockets of the people in Central America, South American and Africa who grew and harvested it. Terms like “shade-grown” and “fair trade” began to turn coffee purchases into political statements. Our unquenchable thirst for the dark liquid—approximately a $5 billion annual market in 2010, according to the coffee industry’s own figures—had at times financed iron-fisted regimes in coffee-growing countries.

Was it really worth nurturing a habit that could give my conscience jitters in addition to my central nervous system?