If a bid by Utah's most prominent family to purchase The Salt Lake Tribune is officially consecrated on May 1, it will register as a meaningful cosmic slap up the side of the head for any Tribune reporter or editor who had a hand in writing the book, Mormon Rivals: The Romneys, the Huntsmans and the Pursuit of Power.

That book, characterized in a subsequent letter to the Tribune editor written by family matriarch Karen Huntsman as "nothing short of supermarket tabloid trash," was published May 1, 2015.

While Utahns who still read newspapers digested the news on April 20 that the Tribune, Utah's most widely distributed and prominent daily paper of record, was being bought by the Huntsman family, the above facts, and any slivers of potential meaning gouged beneath the surface, were swiftly communicated in the following day's paper without near so many words as has been necessary here.

On Page A16 of the Tribune's Thursday, April 21, edition, Pat Bagley, the Tribune's editorial page cartoonist, sketched a photo of a trim Huntsman boy—probably Paul Huntsman, one of Jon Huntsman Sr.'s nine children, and the one whose name was listed as the buyer—arm wrapped around a hefty Tribune reporter. While Huntsman is beaming a white smile, outstretched arm clutching a smartphone in selfie mode, the Tribune reporter, eyes peering over spectacles, has his back turned as he takes notes, a copy of Mormon Rivals protruding from a coat pocket.

This intrigue—how the Huntsmans will behave as newspaper owners and caretakers of an institution that many view as being about as important to the survival of democracy in Utah as a temple marriage is to a celestial-bound Mormon—made quick material for debate when the purchase became public.

But those who counseled Huntsman on the wisdom of buying the paper say the family's desires for the Tribune are pure, cemented upon the principle that preserving an independent voice—a counterweight to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints-owned Deseret News—is well worth their money.

This is also the tone that came from Paul Huntsman, who in a news release announcing the sale, said: "We are honored to be stewards of The Salt Lake Tribune. It is important that The Salt Lake Tribune continues in its indispensable role for our community and to be locally owned. We hope to ensure the Tribune's independent voice for future generations and are thrilled to own a business of this quality and stature."

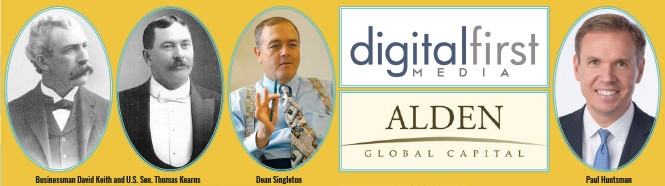

One of the newspaper insiders who the news release says advised the Huntsmans on the purchase is Dean Singleton, who owned the Tribune for a decade, roughly between 2000 and 2010.

Singleton says he's been close friends with Jon Huntsman Sr. for three decades and that—as a lover of newspapers in general, and The Salt Lake Tribune, in particular—he has complete confidence that the Huntsmans will be every bit the proud, local caretakers of the paper that they claim to be.

"They are a very important family in Utah and to have them own the Tribune, in my opinion, is one of the best things that has ever happened to the Tribune," Singleton says.

Full Circle

With shrinking circulation, falling revenue and years of deep budget cuts and newsroom layoffs, purchasing a newspaper might not rank high on an investment banker's to-do list.

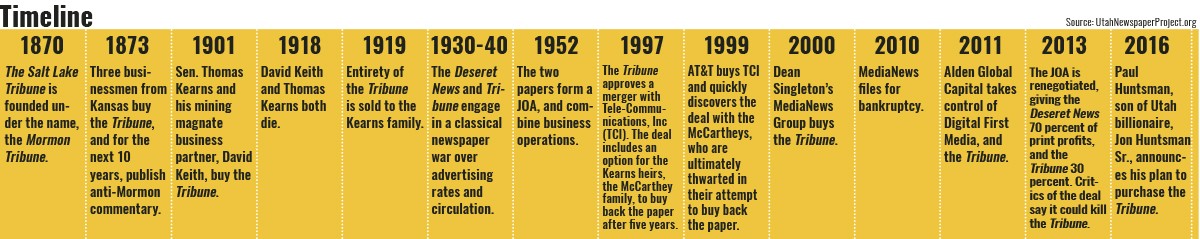

But then again, starting a newspaper in 1870, when The Salt Lake Tribune was founded as the Mormon Tribune, probably wasn't advisable, at least not if money was all one cared about. Like many newspapers across the country, the Tribune took its turn as a rag used for communicating the opinions of its owners. In 1873, a trio of Kansas businessmen bought the Tribune and turned it into an anti-Mormon newspaper.

In 1901, U.S. Sen. Thomas Kearns and local businessman David Keith—both mining magnates—purchased the Tribune. Presumably, the aim in the early era of the paper wasn't so much to make fortunes through newspapering, but to own the state's crown jewel of information and influence. Money is one thing that both men, and their successive generations, including the McCarthey family, were never short on.

Newspapers, though, did end up making vaults of money for their owners, turning annual profit gains of 7 percent between 1950 and 1999, according to the Pew Research Center on Journalism and Media. And, importantly, even as the digital revolution began to herd classified advertising and other revenues onto the Internet, newspapers posted annual profit jumps of 0.5 percent through 2006.

Nestled somewhere in these numbers was Singleton, 65, who bought his first newspaper in Texas at 21, and went on to start MediaNews Group Inc. in 1983, growing the company into the second-largest newspaper chain in America.

The fat times for newspapers, Singleton says, made them ideal for consolidation. Wall Street, Singleton remembers, was eager to throw money at acquiring newspapers—often owned by local families—that were routinely posting robust profits.

"The newspaper business of 30 years ago was the perfect business to consolidate," Singleton says.

While Singleton, who retired as the head of MediaNews Group in 2013, says that if he could do it all over again and be alive and kicking 40 years ago, he wouldn't change much about the way his company came to own more than 50 daily newspapers, including The Denver Post, The Detroit News, the Los Angeles Daily News and the St. Paul Pioneer Press in Minnesota.

But as he looks back on a life as a newspaper magnate, Singleton says two of his newspapers may have fared slightly better than the rest: The Denver Post and The Salt Lake Tribune.

In 1984, Singleton bought a home in Utah. And in 1986, he purchased the Park Record newspaper in Park City. While splitting his time between Utah and Colorado, Singleton says he came to appreciate the unique position the Tribune plays in keeping tabs on the state's power brokers. And in Utah, hovering someplace near the tippy-top of the power tree, is the LDS Church.

"The Tribune has always been what [former Tribune publisher] Jack Gallivan once described as the 'balancing wheel,'" Singleton says. "With the church owning the Deseret News and one of the largest TV stations in the market, it's crucially important that there be an independent voice for news coverage and for editorial comment."

And for the better part of a decade, as the Tribune changed hands, and dozens and dozens of newsroom employees have been purged, the future of this voice grew increasingly uncertain.

It is at about this point—in fact, right at this very moment for The Salt Lake Tribune—where the business model of Singleton and his newspaper-collecting peers has at last shattered to pieces, sending the Tribune, The Boston Globe and other hobbled metropolitan daily newspapers back into the hands of locals with bulging bank accounts.

Singleton doesn't disagree, and says the Tribune—like many other daily newspapers—has come full circle.

In a keynote speech at a newspaper conference in 2009, Singleton says he gave an abridged history of newspapers, saying that "newspapers were originally owned by the people in a local community who had a stake in their community, and money wasn't the big issue, it was serving their community," he recalls.

"I think we are going full circle, where a newspaper is best owned by a local person who cares about the community and the newspaper and how they affect each other," Singleton says.

Dark Business

As much as the Tribune and other newspapers tout the power and reach of the Internet and other digital forms of delivery, few of these newfangled modes of news delivery have been kind to the paper business.

A mere decade ago, if a Utahn were looking for work, he or she turned to the robust classified advertising pages of the Tribune, Deseret News or City Weekly. But seemingly overnight—or about as quickly as the iPhone became a defacto anatomical extension of the human hand—Craigslist and other free classified advertising platforms gutted this important source of newspaper revenue.

Then, as newspapers promoted their free products on the Internet, while simultaneously relying on paid print subscriptions to sell print advertising, most anyone with a basic understanding of economics asked then, and continues to ask themselves, why they should pay money for a product that pulsates for free on their smartphone screens?

As the Tribune weathered these dilemmas—decreasing circulation, fleeing advertising revenue and owners eager for profits—a shadowy deal unfolded in the autumn of 2013 that many believed would at long last bring The Salt Lake Tribune to its knees.

Earlier in 2013, Singleton retired. And, after a 2010 bankruptcy that allowed MediaNews Group to shed hundreds of millions in debt in exchange for a takeover by investors, the company—by name, at least—wasn't really around, at least on paper. The Tribune and many of Singleton's papers were now being managed by Digital First Media, which was controlled by a New York City hedge fund, Alden Global Capital.

The hedge fund proceeded to do what hedge funds do: make money, or at least try. And the quickest way to see cash spew from the Tribune was to hock its assets, including its stake in the printing presses it co-owned with the Deseret News.

Shedding brick-and-mortar assets to satisfy immediate cash needs is one thing. But Digital First also offered the Deseret News the lion's share of the Tribune's future print profits—a move that was either the ballsiest bet ever dreamed up on the yet-to-be-realized fortunes from advertising allegedly available on the Internet, or a very purposeful execution.

Since 1952, the Tribune and Deseret News have been business partners, sharing a controlled interest in the printing presses and the advertising and sales departments. This relationship is known as a Joint Operating Agreement (JOA). A JOA gives a pair of newspapers in the same town the ability to join forces, collude and create an advertising monopoly that, without permission from the government, would be a violation of antitrust laws.

Sen. Jim Dabakis, D-Salt Lake City, has been a vocal opponent of the renegotiated JOA, a loud proponent for the Tribune's survival and, in mid April, said he and a group of multi-millionaires wanted to buy the paper.

The JOA, Dabakis says, and the repercussions of any retooling of the deal, are important for the community to understand and support because at its simplest, the deal has allowed the Tribune and Deseret News to monopolize advertising, often at the expense of other media outlets.

"They have enjoyed that; it has made a huge amount of money for the newspapers," Dabakis says. "This community has sacrificed mightily over the years to keep those two papers alive. It has stifled competition, it has hurt other people in the newspaper business."

Under the Tribune and the Deseret News' JOA, the two papers also shared advertising profits, which in 2013, had the Tribune receiving 58 percent of the profits and the Deseret News grabbing 42 percent. This balance had always favored the Tribune, since it had historically commanded the widest circulation, a statistic that would indicate that it also wrangled the most revenue.

In 2012, the Alliance for Audited Media had the Tribune's daily circulation pegged at 106,619 to the Deseret News' 75,750.

But in 2013, Digital First Media, led at the time by John Paton, executed a deal that seemingly no one wearing a Salt Lake Tribune badge had a clue about: Paton renegotiated the JOA, selling the Tribune's interest in the printing presses, a majority stake on the MediaOne board (the agency that oversees the business and advertising operations of the two newspapers) and flipping the scale on the print advertising profits, halving the Tribune's share to 30 percent and dishing the remaining 70 percent to the Deseret News, for an undisclosed heap of cash.

On Oct. 1, 2013, Terry Orme, who started as a copyboy at the Tribune in 1977, took the reins as editor and publisher. His first duty was to lay off 19 newsroom employees—an otherworldly shitty day for all involved. It wasn't until 18 days later, when some Tribune employees received a cryptic handwritten note indicating that the JOA had been fundamentally retooled, that Orme became aware of the invisible hands that were juking his and the paper's future.

While Orme says he has no problem with his present boss at Digital First, he says he does have "beef with John Paton, the former CEO, who along with [former Deseret News CEO] Clark Gilbert, made this deal happen." Neither Paton nor Gilbert responded to a request for comment.

"At best," Orme says, the JOA is, "extremely short-sighted and poorly thought-out. And that's at best. At worst, I think it was purposely injurious to us. I don't know what their motives were here—only they can address their motives—but I think that was a very bad, shortsighted move."

Just as Orme was taking the helm of the paper, its future seemed less certain than it ever had. Even with 58 percent of the print advertising profits, which still represent the majority of revenues at newspapers across the country, the Tribune had cut, slashed and gutted its staff from a high of 178 in 2006 to 87. Orme says the newsroom is currently 85 strong, and he hasn't had to make a layoff since April 2014. After this layoff, Orme said he would rather resign than hand out another pink slip.

Shock from the new JOA prompted a lawsuit by a nonprofit, Citizens for Two Voices, the leader of which, Joan O'Brien, a former Tribune reporter and daughter of former Tribune publisher, Jerry O'Brien, helped petition the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) to investigate the circumstances behind the new JOA.

O'Brien says the purpose of the lawsuit has always been to prove that the 2013 JOA agreement was entered into illegally because it would hobble the Tribune until the newspaper limped into the grave. And, according to O'Brien, her attorneys have been told that a condition of the Tribune's sale by Digital First to the Huntsmans is contingent on the lawsuit being dropped and the DOJ halting its investigation.

So long as the JOA is renegotiated to give the Tribune a fair share of the print profits, O'Brien says she'll drop her suit.

"You could achieve the aim through a lawsuit, or you could achieve it through a negotiated JOA, so we'll be satisfied, presuming there is a JOA," O'Brien says. "We really don't want to do anything to stand in the way of a transaction that lands the Tribune in the hands of a benevolent local owner."

Though Orme says he knows few details surrounding the terms of the sale, he says he'd put good money on the fact that the Huntsmans have found a way to renegotiate the JOA.

"I'm going to assume that the JOA is being renegotiated and that that's part of it," Orme says. "The JOA is fundamentally bad and wrong and it seems like that's the starting point of creating a viable future for The Salt Lake Tribune. That's kind of Job 1."

A Two-Paper Town

At the height of their popularity, 26 JOAs were entered into between newspapers in two-newspaper towns. Now, according to Rick Edmonds at the Poynter Institute for Media Studies, only five remain; one of which enjoins the Tribune to the Deseret News.

Singleton knows a bit about JOAs. In addition to the Tribune's JOA, the crown jewel of Singleton's former newspaper empire, The Denver Post, had a long-running JOA with the Rocky Mountain News, which folded in 2009.

As it stands, two-newspaper towns have become increasingly rare. And while conventional wisdom holds that more newspapers equal more journalism, which spawns more information, more checks and balances, more well-told stories, better informed citizens and just better stuff all around, newspapers are businesses, susceptible to the whims of markets and the fiscal appetites of shareholders and executive titans.

And, let's be honest, with a phone in your pocket that knows more about you than your spouse, it's hard to imagine the ever-important Millennial generation—or Wall Street, for that matter—entering a state of mourning each time a city loses a newspaper. This is especially true if that city still has another paper.

Over the past two-and-a-half years, as Utahns like O'Brien have bemoaned the fact that the Tribune could disappear, she says she struggled to garner national attention. O'Brien says this could well be due to the fact that, from outside of Utah, anyone could gauge the situation and realize that, while the Tribune might die, remaining would be a newspaper just as old, just as storied and damned near as big as the Tribune.

But the Deseret News is a far cry from an independent voice. Owned by the Mormon church, its website states that its "mission is to be a leading news brand for faith- and family-oriented audiences in Utah and around the world."

Any Utahn who still reads newspapers knows, and has witnessed, the marked difference between the Deseret News and the Tribune—a fact that struck Singleton when he began spending time in Utah in the 1980s.

And, Singleton says, this dynamic makes the JOA in Salt Lake City vastly different from all the others. It also means that for the sake of Utah, Utahns and life here, The Salt Lake Tribune cannot wither away like the Rocky Mountain News.

"I don't know of any newspaper in America that is as important to its local community as The Salt Lake Tribune is to Utah," Singleton says.

On Denver's JOA, Singleton says it was good for Colorado to have two different voices, but "while there were two different voices, it wasn't as critical to have two different voices in Denver as it was in Salt Lake City. It's important that there be two in Salt Lake City for cultural reasons and because the two newspapers have very, very separate readerships."

Had Singleton been calling the shots when the JOA was renegotiated in 2013, he says he would not have made the deal. But he says it was not his place to criticize the business moves made by Digital First Media, and adds that he has confidence that the company was doing what its hedge-fund owner wanted.

"I'm sure they looked at what was the best financial situation for Digital First and they probably made the right financial move, but it certainly weakened the Tribune," Singleton says, emphasizing that nothing can act as a substitute for knowing what the Tribune means to Utah until a person has lived in Utah. "If you've never been to Salt Lake City, you might not know that."

Orme, too, says he has long realized that it's difficult for a newspaper conglomerate, owning as Digital First once boasted 800 "multi-platform" media products, to consider all of the nuances of those myriad products.

"When you're one of 70 some-odd newspapers owned by a chain, they kind of treat you all the same; they kind of treat you as a formula," Orme says. "They don't really ever acknowledge your unique importance to a community. They don't want to understand that. When you have a consolidation of a bunch of newspapers across the country, you're in it for one reason, and that's the bottom line. You don't care about journalism, and I think that was the situation we were in."

Local Control

Orme says the newsroom greeted the prospect of Huntsman purchasing the Tribune "positively," and that the newsroom's reaction was "very optimistic."

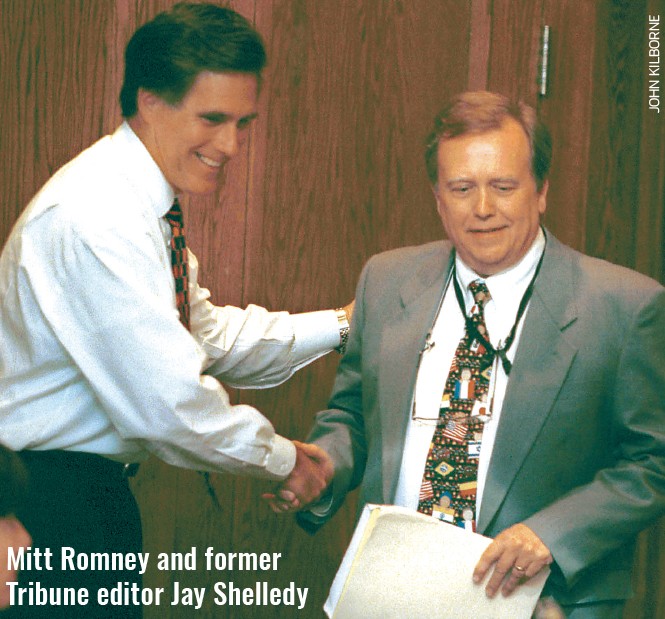

This general air of optimism was reflected by O'Brien, Singleton and former Tribune editor Jay Shelledy, who, along with Singleton, was named as having advised the Huntsmans on the purchase.

For Orme and his stable of reporters, editors, copy editors and page designers, the past couple of years, operating under the knowledge that half of the profits that once filled the paper's coffers are now flowing to the competition, and that the owner is a cash-hungry hedge fund, have been riddled with uncertainty.

While any devoted newspaper lover in Utah could speculate for days about what the Huntsmans might do with their time-tested new toy, there are a few facts surrounding the sale that have Orme resting easy.

The first involves what the Tribune is, what it has been and what he hopes it will long continue to be: an independent voice for Utah. "I do think they are buying something not because they want to mold it into something else," Orme says. "They bought the Tribune because they like what it is and what it stands for. I'm feeling good, and I'm getting a sense that their motives are in our best interest and are genuine."

The second is the reality that the newspaper business, while not so profitable as it was during the bulk of the 20th century, is nevertheless still profitable. Orme cites the business pedigree of the Huntsman family, saying he imagines that they have realistic expectations about the newspaper business.

A Huntsman spokesperson says the only comment from the family is the news release announcing the sale.

From the day in 2013 that it became public that the JOA had been renegotiated, Tribune supporters trumpeted the importance for the newspaper to fall back into the hands of a local owner.

Just one week before it was announced that Paul Huntsman, president and CEO of Huntsman Family Investments, a private equity fund, had entered into a "definitive agreement" to buy the paper, as the news release announcing the sale noted, Dabakis appeared on the Tribune's web chat show, TribTalk, and said he was part of a group that was preparing to buy the Tribune.

Dabakis says his group was, and is, "willing, able—even anxious—to buy The Salt Lake Tribune."

Dabakis, a gay, unapologetically liberal politician who never seems too worried to stick his fingers in the eyes of the church, also says that maybe his threat of buying the Tribune forced the church to take a long, hard look at Huntsman's proposal.

"We were able to make Deseret News publishing look at it and say 'We have to choose between Dabakis and his group, and Huntsman? Let's go back to Huntsman and see what we can do,'" Dabakis says.

While Dabakis is optimistic that the Huntsmans will be solid owners of the Tribune, he says a part of him is nervous about having a historically staunch Republican, and Mormon, family running the paper.

"It's important that the Huntsmans make a pledge that this is going to continue, [editorially], to be a progressive newspaper and a counterweight to our community, along with City Weekly, and that they make that announcement," Dabakis says.

If history has indeed swung full circle, and the Huntsmans are the perfect caretakers of their local paper partly because they aren't starved for riches, then it's hard to imagine that they won't put their stamp on the paper like every other owner has.

While Orme says he has no reason to believe the Huntsmans intend to lay their hands on the newsroom and begin manipulating coverage to suit their desires, he imagines the editorial pages will become the pages of those to whom they belong: Paul Huntsman.

During his 40 years at the Tribune, Orme has had a front seat for the good times and bad, rising from among the lowliest positions at pre-Internet newspapers, to his current perch as editor and publisher, the highest position at the paper, squared.

Having seen the paper in local hands before, Orme says it's inevitable that conflicts of interest and fiery debates will arise as the Huntsmans, newsmakers in their own right, grapple with a newsroom that, in order to be a newsroom, must operate separately from the machinations of its owner.

"This is a family that makes news, no question about it, and we're going to have to cover them and that's always a challenge," Orme says. "There's always some very hard discussions and negotiations that take place, and I think we'll just take them as they occur and do our best to be as transparent to our readers and let them know when there is some potential conflict in what we're doing and just be up front. I think the Huntsman family and Paul Huntsman would agree with that."

And then there is that matter of the "tabloid trash," as Karen Huntsman called it, and the veteran political reporters, Thomas Burr and Matt Canham, who penned it. Orme points out that the publication of Mormon Rivals wasn't the first time that the Huntsmans have taken issue with the Tribune's coverage of them.

And in the book's case, Orme says he handled the situation just as he does with any reader, source or subject of a news story that takes issue with the newspaper's coverage. "Mrs. Huntsman wrote a pretty strongly worded letter to the editor about Mormon Rivals," Orme says. "We published it. I think we've moved on."

As all of this takes shape, though, it's important to keep an eye on what Orme says local ownership, and deep pockets, can provide to make the Tribune a better paper: investment.

During the Digital First era, Orme says there was only one message emanating from the company's New York City headquarters: "Reduce, reduce, reduce."

Even as Digital First mandated its stated goals, implicit in its name, to harp on the importance of this magic digital revolution, Orme says there was no digital investment. The Tribune, Orme says, has created digital apps, retooled its website, created new platforms for iPhones and other digital devices, without a single penny of added funds. "No encouragement," Orme says. "And we've had no investment, which is really needed."

"We have scraped those innovations we have had, we've had to scrape them within our own newsroom budget and resources with employees we have," he continues. "It's just been an added job for our people."

Singleton, who, if not the greatest consolidator of newspapers in American history, ranks high among them, realizes that he might sound like a hypocrite for espousing the beauty in local control of newspapers.

Even as his company gobbled up papers from coast to coast, he says the robust financial realities for newspapers at the time allowed him and his lieutenants to operate the papers in a local manner, by ensuring that locals were running the shops. And in hindsight, Singleton says his close ties to Utah and to Colorado left both The Denver Post and the Tribune faring better than the other papers in his care.

"Now that I can look back and I'm not involved anymore, the two newspapers that were in MediaNews that were local to me were probably better newspapers than some of the other group because we were making decisions based on local information and not just metrics," Singleton says.

As for any concern over what Paul Huntsman, or any member of his family, will do with their newspaper, Singleton says there isn't a worried bone in his body. Sure, he says, the Huntsmans are Mormon. Sure, Jon Huntsman Jr. was the Republican governor of Utah. But what the Tribune needs more than anything else, and appears to be getting, is an owner that gives a damn about its survival, and its place within the local landscape. And Singleton says he can't think of a better champion than Paul Huntsman and the Huntsman family.

"To me, it was important to find that unique owner, who would be there to be the steward," Singleton says. "Somebody that cares about that community needs to own the Tribune and that will happen now." CW

Correction: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated that the last layoff to occur at The Salt Lake Tribune took place in October 2013. The last time a layoff occurred at the Tribune was in April 2014.