Then 12-years-old Ruiz rode in front of a parked van and onto Redwood without seeing a white car approaching him at 45 mph. Upon impact, he flew 40 feet and landed on his head in the street. His skull fractured in five places, a portion of his brain extruding from his left ear.

By the time a comatose Ruiz was flown by medical helicopter from the blood-drenched street corner in West Jordan to Primary Children’s Medical Center on March 25, 2004, he was bleeding from every opening in his body. Doctors gave him a 2 percent chance of survival. His mother, Brooke Gonzalez, told them that was unacceptable. While the doctors removed a piece of his skull to let his brain swell, 50 relatives and friends of the family gathered in the intensive care unit’s waiting room area.

Over the next few days, Ruiz’ head swelled to three times its normal size. It touched the ends of his pillow, leaving him unrecognizable.

Gradually, the swelling came down, and nine days after the accident he was taken off of the ventilator and began breathing on his own. As the days wore on, he opened his eyes, grunted and moaned. He whispered nonsensically and would get mad when no one understood him.

Doctors predicted that Ruiz, whom Gonzalez calls “my medical-miracle boy,” wouldn’t know any language and would have a mental age of 1. Three weeks after he was admitted, the doctors reattached the left side of his skull. One of his first words was “Fuck,” spoken angrily to a nurse, his mother recalls. The obscenity had the nursing staff cheering because the first part of the brain to wake up is typically the uninhibited part.

A few days later, the doctors told Brooke Gonzalez they thought Ruiz could go home. When she questioned whether their decision-making was related to her not having insurance, they told her she would receive help at home “to give me time to apply for financial assistance.” On April 20, Ruiz was discharged.

Two weeks after Ruiz had gone home, the therapists and home-health-care nurse stopped coming. The Gonzalezes were alone with a child who needed 24-hour supervision, incoming bills totaling $376,000 in just the first two months, and monthly therapist costs of more than $5,000. Subsequently, medical bills forced the Gonzalezes to sell their home and declare bankruptcy. They’ve had to move to rental properties several times to keep Ruiz’s medical benefits.

“Not having any help for him was hard,” Pablo Gonzalez says. He took unpaid time off from his tire-delivery job to help with his son. “We had no idea how to care for him.”

ON YOUR OWN

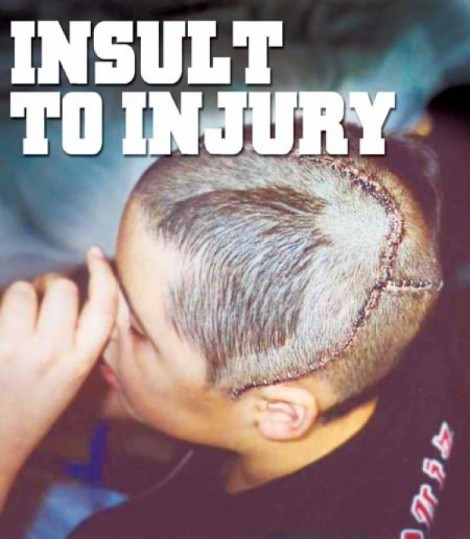

In the six years since Ruiz’s accident, he and his family have struggled with the repercussions of his traumatic brain injury. In particular, he and his parents have felt increasingly betrayed. The hospital administration betrayed them by sending Ruiz home less than a month after he was admitted with horrendous cranial damage. Family and friends betrayed them by drifting away, tired of the never-ending drama of Ruiz’ medical and emotional needs. The Jordan School District betrayed them by failing to protect their vulnerable son from vicious bullying.

Ironically, the family had as good a chance to adapt as anyone, because Ruiz’s mother, Brooke Gonzalez—her son carries her maiden name—was Utah’s Brain Injury Association [BIA]’s administrative assistant for two years after Ruiz was born. She knew more than most the lifelong struggles her family and son faced after his accident. Unlike many families who, unable to cope, seek to institutionalize their brain-damaged relative or put them into a nursing home, she has fought relentlessly for financial and medical assistance for her first-born. “She is a very exceptional mother,” BIA’s director Ron Roskos says.

Started in 1984, nonprofit BIA provides resources, help and a willing ear for victims and families struggling with brain injuries. BIA is in a dilapidated, half-empty building in South Salt Lake with chimes on its front door to alert the two full-time staff to visitors.

Brooke Gonzalez and Lynda Valerio have been best friends since they were 8. When Gonzalez left the BIA in 2001, Valerio took over her position. A brain injury, Valerio says, isn’t just blunt trauma to the head. “It’s strokes, concussions, tumors—anything that happens within the brain, that affects it, on a mild-to-severe level.” A brain-injury survivor’s future is often bleak, with 50 percent of those suffering brain injuries developing Alzheimer’s, according to BIA statistics. Every week, six more Utahns join the 44,000 state residents already living with brain injuries.

One of the BIA’s on-and-off clients, Margaret Burke, died on Feb. 27, 2009, at the age of 60. On the surface, Burke and Ruiz had little in common. Unlike Ruiz’ car accident, Burke’s Wisconsin-based sister Betty Henningfeld attributes Burke’s first brain injury to a 1997 stroke, complicated by paranoid schizophrenia. BIA’s Roskos believes domestic violence and several falls may also have injured her brain.

Burke drifted from job to job, from one abusive relationship to another, and endured at least one period of homelessness. If Burke “could have had some other help” beyond what the financially strapped BIA could do for her, “she’d still be with us today,” Roskos says. “Her body just kind of wore out.”

Yet, Ruiz and Burke are two ends of the same spectrum. One has a close knit family, the other was alone. One has a home, the other searched for one much of her adult life. One is young, the other, in her final years, was old before her time. What unites them is that they both fought to re-enter a society indifferent to the devastating long-term impact of brain injuries. “If Nathan didn’t have the support he has, he’d become a Margaret,” Roskos says. With or without family and state support, Ruiz and Burke experienced violence, marginalization, neglect and abandonment. In Burke’s case these had fatal consequences.

A cruel irony of brain injuries is that victims aren’t eligible for help from federal- and state-funded Valley Mental Health, itself cutting back on services for its mentally ill clients. That places all the more emphasis on the underfunded BIA.

Roskos and Valerio dream of a place where people like Burke and Ruiz can go for medical treatment, services, guidance and a roof over their heads. “We don’t want to be just a hand-out place, a last resort,” Roskos says. But, after 25 years, it’s still just a dream. One legislator, Roskos says, told him that treating brain injuries “is like pouring sand out of a boot. It never ends.”

The once-gregarious and popular Ruiz, who ran with a tough crowd before his accident, knows his brain “is never going to be better.” But, he wants to get the best out of the hand life has dealt him.

“The what-ifs list is off the charts,” he says. “The what-I-have list is very simple but can be made better.”