- "Pissing in the Wind"

Recently named Executive Director of the Salt Lake Art Center, Adam Price has made it part of his mission to take what can appear difficult—modern art—and make it more accessible to the public. What better way to do that than an exhibit of miniature golf holes designed by local and national artists? Eighteen submissions were selected for the “Contemporary Masters” exhibit, creating a playable full course of miniature golf in the space of the gallery.

Many of the artists used a theme to govern the design of their hole, a number of which were unlikely, like Los Angeles-based Spencer Douglass’ 17th hole, “After the Summit,” with mementos of the 1978 Camp David Peace Summit led by President Jimmy Carter between Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin and Egyptian President Anwar Sadat. Peter Everett’s 13th hole, “Donkey Kong,” somehow manages to suggest Tibetan Buddhist themes in its recordings of monks chanting—perhaps including reincarnation as you make attempt after attempt—combined with playing video games. Andrew Callis’ “Pi Hole” takes the number as its theme, dissecting a spherical playing area into segments according to the intervals in the numerical process that can continue endlessly.

“I tend to work a lot with spirals, as they are a passageway into infinity,” Callis explains. “For this, I was looking for a didactic element—looking into pi, and how it charts a spiral, beginning from the middle, with steps. So it’s really about how there is this circle widening out. It gave me a solid structure to work with, and made it easier to make decisions.”

Loggins Merrill’s hole, titled “Industry,” requires a different physical exercise than ordinary golf: After you’ve introduced the ball to the playing surface, you must ride a bicycle to move parallel wooden slats back and forth to advance the ball through the middle section toward the hole. It’s a metaphor for not only physical exertion, but also capitalist economy: its found materials, like weathered-metal plating for the tee area, create an industrial atmosphere.

“Most of my sculpture pieces have to do with taking different industrial types of materials like the cement and plywood and metal, finding them in their natural shape, and then bringing them together into a piece of art. So I’ve taken parts of different art pieces and combined them into a playable art piece,” Merrill says.

Merrill’s work is about a strange kind of functionality, in that every piece in the puzzle serves to guide you—albeit with difficulty—to the end result: “If your friend is playing, you can really mess them up riding the bicycle on that one, you can be a little devious. I think artists should be a little devious.”

Tiffini Widlansky, a trustee for the art center and 337 Project, explains that even more so than most sculpture, the experience of the show depends on the viewer’s perspective, which “changes as you make your way around the course to play the different holes. It’s really interactive.” The show has been made available to local groups for benefits and other events, and has already seen a lot of school groups come through. Each hole is like a brief view inside the artist’s mind of what their imagination conjured up within the strictures of the game. It’s not only a lot of fun, but also leads to intriguing questions about the nature of art.

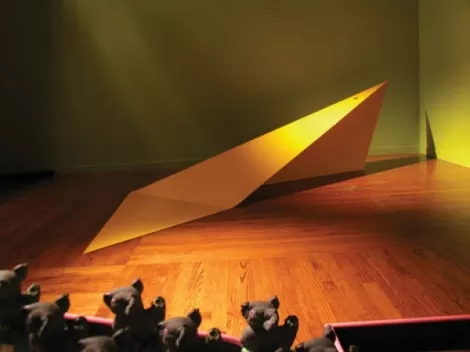

John Bell makes a comment about golf and life with the 9th hole, “Pissing in the Wind.” “It was a little jab at the futility and pointlessness of a game like golf,” Bell explains. The painstaking work involved in making the piece is belied by the smooth, angular surface of the aluminum sheeting with powder coating, leading up a “slippery slope” to the hole at its apex. “Minimalism is supposed to look tossed off, but it’s one of the most difficult forms of art … to get it just right, you’ve got to work and work and pare things down until you get an elegant shape like that.” Unlike most of the other works in the show, it’s designed to be a stand-alone sculpture outside the golf context.

“I believe [the hole is] ‘par infinity,’” says Bell, “but it’s also like, nothing in life comes easy. There’s also being the big cosmic winner when you realize the futility of it, and you’re OK with that.” It also answers the question: What artistic style makes the most difficult golf hole?

CONTEMPORARY MASTERS: ART-INSPIRED MINIATURE GOLF

Salt Lake Art Center

20 S. West Temple

801-322-4323

Through Sept. 16

SLArtCenter.org

Free