Page 2 of 5

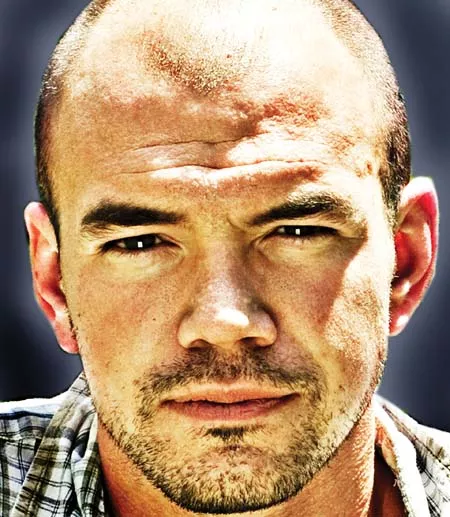

Louis Godfrey: You’ve said that you went down to BLM office without the intention of registering for the auction, and that the action was spontaneous. At the auction, did you just notice that the security was lax, that anyone could sign up? How did you realize, that, yeah, this could be done?

LG: So, in a sense, you were able to do this because you had a lack of knowledge about the process?

TDC: Yeah. I suppose somebody who had more familiarity with the process would have thought, “There are normal procedures that are supposed to make sure that bidders are bonded ahead of time, so you figure there is no way to do that.” But, of course, they weren’t following those procedures.

LG: You registered under your own name?

TDC: Yeah.

LG: Was it nerve-racking at all?

TDC: The part that was nerve-racking was before I made a firm commitment to go all the way and start winning every parcel, when I was just driving up the cost. I had to pay attention to how the other bidders were acting and to their body language when I bid.

LG: What were your general impressions of the auction?

TDC: It was almost thoughtless and mechanical. There was a very cold feeling to it. There was another woman sitting across the room, another activist who I know, and she actually started crying. Later, she told me it was because the whole thing was just so inhuman …

LG: … Seeing the natural world reduced to plots on a map?

TDC: Yeah. And there was no acknowledgement of the land or of any of the consequences of the actions. It was just this many acres in this county, and that was it, and then a price was assigned.

LG: You have said before that, when you made the decision to win every parcel, a sort of calm came over you, and you gained a level of confidence, almost like you were having a spiritual experience. Can you explain that?

TDC: I think that was because I had firmly chosen my path, and I knew that I was doing as much as I possibly could, and I knew that my actions were in line with my sentiment about how severe this crisis is. Up to that point, I had always felt on some level that this crisis was so huge, and I wasn’t doing enough. That riding my bike and saving energy and writing letters—that I wasn’t really doing enough. And so, at that point, I knew I wasn’t holding anything back. I think that that is where the calm came from.

During a break in the auction, DeChristopher was escorted out of the auction room by BLM officers and taken to an empty office somewhere in the back of the building. DeChristopher was very forthright about his purpose at the auction, and he says the tone of the officers’ questioning was exceedingly polite. He even detected a hint of sympathy from the officers, who were all about his age and who had probably joined the BLM out of a desire to help preserve public lands.

But mostly, the officers seemed confused. Not just about what to do with DeChristopher (they spent a good deal of time that afternoon on the phone with the U.S. Attorney’s Office trying to figure that out), but why a straight-A student with no criminal record would do something like that.

Legitimacy

For Henry David Thoreau, the natural world is only properly understood when men do not impose their own purposes upon it.

Thoreau was jailed in Concord Massachusetts on July 23, 1846, for refusing to pay a poll tax. He had refused to pay such a tax for years, objecting to the state of Massachusetts’ passive support of Southern slavery and the Mexican-American war. Thoreau spent one night in jail until, to his chagrin, a relative paid the tax, and he was released.

Recounting the experience in his seminal essay “Resistance to Civil Government” (later re-titled with a phrase Thoreau had coined, “Civil Disobedience”), Thoreau wrote, “If [an injustice] is of such a nature that it requires you to be the agent of injustice to another, then, I say, break the law. Let your life be a counter friction to stop the machine. What I have to do is to see, at any rate, that I do not lend myself to the wrong which I condemn.”

DeChristopher first read Thoreau when he was 17. And, as we discuss it, he concedes that, far from being a selfless act, civil disobedience is derived from a selfish impulse—to extricate one’s self from complicity in corruption. This is true whether it is Thoreau refusing to pay a poll tax or Leo Tolstoy counseling war resisters. At its best, though, civil disobedience can reflect that disobeyer’s aspirations for society as a whole, and can serve as a bond between the individual and society.

When DeChristopher was 18, he read Edward Abbey’s The Monkey Wrench Gang. The novel, published in 1975, tells the wild tale of four eco-avenging misfits sabotaging development projects throughout the Western United States, with the law not far behind. If there were a particular genius to DeChristopher’s actions at the auction, it was that, like Abbey’s writings, multiple generations of environmental activists were able to recognize their own idealism in it.

But, DeChristopher has a complicated relationship with the legacy of Edward Abbey. In March, he was invited to take part in a commemoration of Abbey at Ken Sanders Rare Books (Sanders himself was a close friend of Abbey, who died in 1989). DeChristopher talked about the meaning that works like The Fool’s Progress and Beyond The Wall hold for him, but he mostly focused on the differences he has with Abbey.

“There is never really that happy of an ending with Abbey,” he says. “And I think that that is in part because that style of monkey wrenching isn’t very effective at doing anything. And I think that’s part of the point that Abbey was making with his books, that people take this action to make themselves feel better, rather than to really effect change.

“And, actually Ken Sleight [who inspired the character Seldom Seen Smith] talked about some of the monkey wrenching that he and Abbey would do, and it was mainly because they were angry and they needed a way to express that.”

The local media has thoughtlessly branded DeChristopher as a “monkey wrencher” but, according to both Sanders and Sleight, what DeChristopher did at the auction does not fit the definition. Monkey wrenching is pranksterish, destructive, and its goals are limited, none of which fairly describe DeChristopher’s civil disobedience. But, more importantly, monkey wrenching is supposed to be anonymous—the whole point is to not get caught. DeChristopher never tried to evade responsibility for his actions. His very intention was to personally confront authorities by getting arrested.

DeChristopher’s formative years were also spent studying American social movements, some of which included radical action. Of particular interest was the civil rights movement with its lunch-counter sit-ins and interstate Freedom Rides (Martin Luther King Jr. wrote in his “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” “The purpose of our direct-action program is to create a situation so crisis-packed that it will inevitably open the door for negotiation”). The women’s suffrage movement was similarly significant; women picketing at the U.S. Capitol—while commonplace today—was radical enough at the time that police on horseback beat and drove the women away.

There is, however, a fundamental difference between civil disobedience employed by past social movements and civil disobedience regarding climate change. With past movements—whether they were in opposition to Jim Crow laws in the American South, colonial rule in India, or apartheid in South Africa—the civil disobedience reflected a greater opposition by members of an oppressed community. This opposition stemmed from what the political theorist Hannah Arendt called, “The simple and frightening fact that [the people engaged in disobedience] had never been in included in the original consensus universalis—the tacit social compact—of [their respective governments].” Because of this initial exclusion, individuals felt that they had the right to deny the validity of the compact, to essentially withdraw from it, and force society to amend it.

With climate change, the civil disobeyers do not deny the validity of the social compact. But they see that action, or lack of action, by the state threatens the long-term survival of that compact, and of society itself. This model of civil disobedience, rather than being a withdrawal, is actually an engagement—a plea for more and different intervention by the state.

This is not to say that climate-change-related civil disobedience is less morally legitimate than past civil-disobedience movements, because assessing the legitimacy of any act of civil disobedience is necessarily a retroactive process.

Eminent legal scholars such as John Rawls and Ronald Dworkin have tried to formulate what preconditions must be met to justify the use of civil disobedience—the action must “defend the principles of justice,” or it must be in defiance of a law that “wrongly invades upon one’s rights against the government” (respectively). But none of that can erase the fact that when someone breaks the law, they forfeit an assumed legitimacy and the morality of their actions becomes relative. Animal-rights activists freeing minks from a fur farm, ATV enthusiasts riding en masse on restricted federal lands—one person’s civil disobedience is another person’s criminal activity.