At 7 a.m. on Dec. 20, 2012, I walked downstairs in my usual morning daze to feed our cat, Hussy. Turning to go back upstairs, I saw that my son David, visiting for the holidays, had fallen asleep at his computer in the adjacent, still-darkened family room. He sat on the couch, his computer open on the coffee table in front of him, head resting on the computer top, arms dangling to the floor. I spoke to him from the stair landing loudly enough to wake him: “David, go to bed and get some sleep.” But he did not answer.

Just three days into his 30th year, David was dead.

While my husband, Rick, called 911, I sat next to David, put my arms around him, and rubbed his broad shoulders and back, as if I could warm him back to life. I tried to comprehend what it could possibly mean that my son, for whom I would gladly have given my own life—what mother wouldn’t?—was dead. I glanced around and saw his notebook with a long to-do list lying next to the computer: “Recruit help for Saturday/Look for car/Buy Final Cut Pro/Research Scriptshare ...” And then I saw the bottle of Percocet.

The autopsy report showed he had the equivalent of two glasses of wine and 0.58 ug/ml of oxycodone (the main ingredient in Percocet) in his system. Just enough.

When you think about someone dying unexpectedly, you think of a car accident, an illness. But, according to Utah’s Department of Heath, more Utahns die accidentally from prescription-painkiller overdoses than just about anything else.

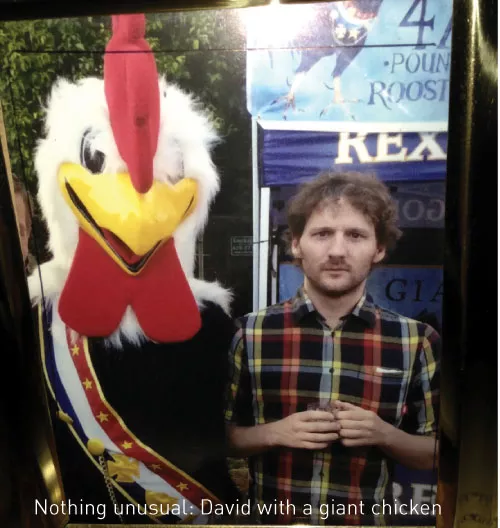

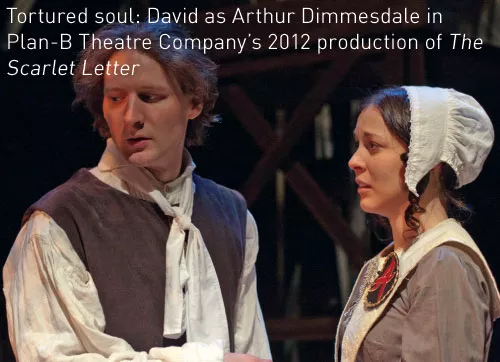

As I write this, I’m looking at a photo of David standing next to a man in a chicken costume at what might be a state fair. David looks straight into the camera with a serious face, as though all is normal, as though he is not being photographed with, well, a fowl. I laugh, because it is so David: so unpretentiously, quietly funny. Someone who lifted others all the time because of, at least in part, his willingness to make himself silly. At the time of David’s death, Jerry Rapier, directing producer of Salt Lake City’s Plan-B Theatre Company, with whom David had worked, described him as being “the light of the room, every room he entered, every time he entered it.”

The laughter, when it comes, however, is always in short spurts, and is often followed by anger and varying degrees of despair. David did not want to die. David should not have died.

A CITY OF ADDICTS

The Centers for Disease Control & Prevention reported recently that the number of accidental prescription-drug overdoses in the United States has reached 16,500 per year—a small city of deaths—claiming more lives than illegal heroin and cocaine overdoses combined. In Utah, there are approximately 400 accidental drug-overdose deaths per year, according to Utah State Medical Examiner Todd Grey—almost 20 percent more than the national average.

When I met with Grey to discuss David’s death, he put my own grief into some context, stating, “If we do not have at least one prescription-drug death a day, it is a surprise.”

Of the most commonly abused prescription drugs, opioids—used for pain relief—are the stars. Federal statistics now show nearly 2 million individuals struggling with addiction to the opioid-based painkillers Percocet, Lortab, Vicodin and morphine. Opioids are dangerously addictive because of the euphoric effect they produce in the brain. That effect lessens over time, however—and as it does, more of the opioid must be introduced to obtain the same effect.

The addictive nature of opioids is not selective. They do not affect only the weak, the homeless or the mentally ill. They affect everyday people, who begin taking them believing they are an acceptable treatment for pain, and then find they cannot live without them.

In an interview with Dr. Sanjay Gupta in November 2012 on CNN, former President Bill Clinton, after suffering with two close friends who lost their sons to accidental overdoses, emphasized that these deaths are happening to people who “are your friends and neighbors—and you don’t know about it.”

You don’t know because of the stigma and shame associated with the word “addiction.” To what extent was I ashamed, and did that shame, in some way, play into David’s death?

This tale is in part my search for that answer, if not my penance.

AN ACTOR IS BORN

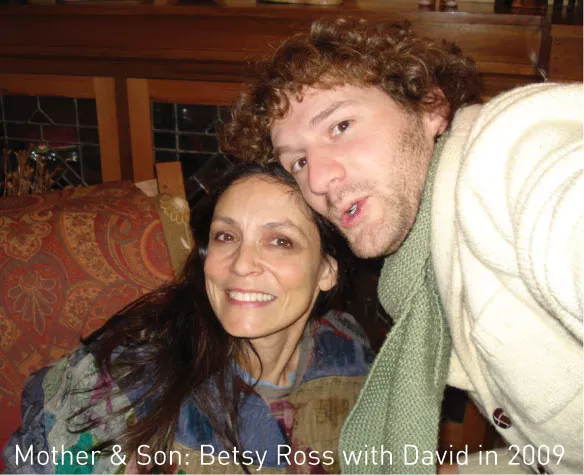

David had a knack for entrances; his eventual choice of acting should have been no surprise to us. He was born 10 days early, on Dec. 17, 1982, in Bloomington, Ind., an hour after I had driven his father to the airport, 90 minutes away, to fly to Salt Lake City for the funeral of his own father.

David was born with a full head of black hair that turned white-blond only a few months later. The congenital back issues that would become his second-most challenging opponent were hidden within a beautiful shell.

David was the second of four children. When I look through early photographs of Scott, David, Jessica and Carly, it is obvious that David was the mischievous one. I have to giggle at the one taken when David was 2 years old, covered in his father’s shaving cream. He looks up at the camera with no fear at all, as proud of the mess he had just made as if it were a beautiful work of art.

David was drawn to the performing arts at a young age, acting at the Utah Children’s Theatre, the University of Utah’s Theatre School for Youth, Pioneer Memorial Theatre and Salt Lake Acting Company, all before reaching high school.

It was during his first year at East High that he convinced us that he wanted to go to a boarding school for the performing arts in Michigan. Accepted into the prestigious Interlochen Arts Academy, David alternately flourished and faltered as he took the necessary steps to grow into himself and his huge talents. It was at Interlochen that he began pushing the boundaries, directing for his senior project a mixed-media performance of film and theatre that won him praise from some and opposition from others. Challenging boundaries was an approach to art and life that would remain with him to the end.

Even while David’s creative talents blossomed far away, he remained loyal to the longtime friendships with his SLC buddies, including best friend Pat Fugit. David and Pat had been friends since grade school. Pat says they met when he saw David pretending to slip on a banana peel on the grade-school playground. They spent too much time thereafter seeing who could stage the most convincing falls. They never outgrew the competition; each visit to our home was punctuated with the “bam” “crash” “pow” comic-book sounds of the boys seeing who could fall down the stairs most convincingly. As they progressed from 5-foot-nothing 10-year-olds to 6-foot 20-somethings, those crashes became more impressive.

David’s friendship with Pat grew even while Pat went on to acclaim with his debut role in Cameron Crowe’s film Almost Famous. Pat would rely on David to read the scripts Pat’s agent sent, always looking to David’s sense of what was good and what was bad. In fact, all of David’s friends would look to David for that remarkable, discerning creative intellect.

At some point, David and Pat discovered their shared musical interests and talents. In 2004, they released their first CD, Eddie Do, as the group Mushman, named after Harvey Mushman, an alias used by Steve McQueen in his racing career, and an idol of theirs. In 2008, they released their second CD, Lost Like Children.

David drew on a store of sweetness mixed with a seriousness that belied his age as the main songwriter and lead singer, while Pat contributed a talent for guitar riffs and a foil to David’s humor.

Many of the songs David wrote dealt with death and existential crises—not in a tortured way, but one that was inquisitive, childlike and sweetly sad.

In “Eddie’s Balloon,” probably Mushman’s most popular tune, David writes:

Eddie was afraid to die

He’d subtract and multiply

But never know why.

She departed far too soon

Leaving him a red balloon

To let go in the sky.

From his window Eddie watched it soar

Till he couldn’t see it no more

Who knew heaven was so high?

....

Mommy I’m afraid to die it’s sad

But it won’t be that bad

When I’m back with you.

After moving to Los Angeles in 2009, David worked for a film-production company before returning to Salt Lake City late that year to co-produce and assistant direct Dustin Defa’s feature film Bad Fever, which played at the South by Southwest film festival and was named one of New Yorker reviewer Richard Brody’s top 27 films of 2012.

Entering what was probably the busiest and most productive period in his life in 2010, David played the lead male role in the feature film Must Come Down in Salt Lake City. The movie went on to appear in numerous film festivals, with reviewers finding David to be “the film’s not-so-secret weapon.”

At the same time, David initiated the planning for the launch of his brainchild, The New Works Theatre Machine, an experimental theater in SLC. David endured the travails of bringing this fledgling business to life and produced two plays, Go to Hell in December 2010 and Ride Me: A Play with Cruel Intentions in May 2011. He was named by The Salt Lake Tribune as one of Utah’s eight emerging artists in 2011.

But in the midst of all his accomplishments, David was struggling with addiction to painkillers. It began, and ended, in the familiar clinic of our family doctor.

DOCTOR-SHOPPING

It was to Dr. Smith (whose name has been changed) that David first went as a teenager with his back pain. It was Dr. Smith who prescribed David his first opioid (Lortab) in 2008, along with Xanax and Adderall for anxiety and difficulty in concentrating, thus beginning David’s relationship with addictive drugs.

Over the years, that “relationship” escalated, and as David’s tolerance levels rose, Lortab, a Schedule III-controlled substance, became Percocet, a Schedule II-controlled substance. David could get a month’s worth of 5-milligram tablets of Percocet from Dr. Smith whenever David was in Salt Lake City.

And when David was in Los Angeles, he was able to obtain Percocet in 5-milligram tablets from clinics there. Consistent with an increasing tolerance level, David took multiple tablets at a time, resulting in a need for additional prescriptions, which led him to doctor-shopping.

I didn’t know about the doctor-shopping until 2012, when a doctor at a Rapid Care clinic in Los Angeles was the first to run David’s name through the federal controlled-substances database operated by the Department of Justice. The doctor found multiple prescriptions in David’s name for Percocet and asked David’s girlfriend, Ashly, to come in, along with David, and talked with them both about the problem.

Ashly called me and, with David’s consent, we decided he should return to Salt Lake City to see Dr. Smith and get to the bottom of the problem.

I don’t really know the extent of David’s feelings about that trip. I know he felt shame about his misuse of Percocet and the doctor-shopping, and perhaps being made to feel like a child at the age of 29, but I wonder if there wasn’t a part of him that was relieved to have it out in the open, to have some help in putting Percocet behind him.

THWARTED INTERVENTION

I went with David to visit Dr. Smith on June 28, 2012, to support him and to make sure he told the whole truth about his substance abuse.

David admitted to Dr. Smith that he had been taking five 5-milligram tablets of Percocet at a time, multiple times a day, contrary to the label instructions.

I braced myself, expecting to hear the term “addict,” but it never came up. The words “addiction” and “addict” were, in fact, conspicuously absent from the conversation.

Dr. Smith focused on the underlying reason for the use of Percocet: David’s back pain, with the implicit reasoning that eliminating the back pain would eliminate the need for the painkillers. He helped us arrange to see another doctor who could administer a cortisone shot to David’s back.

What Dr. Smith did not do was act on the concern about David’s chronic use of Percocet for lower-back pain that he had documented in a previous appointment, according to his own clinic notes, which I obtained after David’s death. But in our meeting, Dr. Smith downplayed the amount of painkillers David was taking, telling us he had many patients who took much more than David.

After four years of prescribing him painkillers ranging from Lortab to Percocet, in addition to the Xanax and Adderall, Dr. Smith had led David down the path of addiction and stranded him there.

As David’s mother, I was relieved to hear from our trusted family doctor that my son was not an addict. That was how I bought into the shame of addiction. I was only too happy to have a doctor tell me David’s problems could all be solved by a cortisone shot in his back.

And that was how we might have saved David, but didn’t.

A MOTHER’S ODYSSEY

I was sick soon after David died, a bout with the stomach flu. While on the way to the bathroom, I passed out, falling to the floor so loudly that Rick was roused from sleep and came running to my side. He told me later that I was lying on the hardwood floor, not breathing, with my eyes open—staring straight up, unseeing. After yelling at me and shaking me (none of which I remember), Rick heard a sharp intake of breath and I rolled onto my side. I remember him wiping my brow with a cold washcloth, shepherding me back to bed and taking care of me through the night.

We were lying in bed watching an old movie a few days later when Rick asked what had been on both our minds since that event: “Would it have been OK if you had died?”

“Maybe,” I answered, and started crying.

After a few seconds, I explained, “I don’t spend my time thinking about it and wishing I were dead, but if it happened ... it would be OK.”

Softly, he asked, “Why?”

Just as softly, I replied, “Because I would be with David.”

As I cried, I attempted a mother’s explanation of something that is impossible to explain: “It’s just such a deep sorrow.”

After David died, I went on a fact-seeking odyssey to come to terms with his death and to confront my part in it. As mothers, we are our children’s first protector. We nurture, instruct and release our children into the world, but we never lose the instinct to protect. When a child dies before us, I can’t imagine a mother exists who does not ask, “How did I fail? What could I have done to save my child?”

Every day, every day, the words come to my mind: “How could this have happened? How could this be?” And, “How did I fail?”

I visited the doctor in Los Angeles who had “outed” David in June 2012. We spoke at length about the problems involved in addiction generally, and the missteps with David’s situation in particular. There was no sugarcoating, no avoiding the word “addict” this time. David’s actions—taking five pills at a time, contrary to the prescription directives, and doctor-shopping—were textbook indicators of addiction. Any physician, when confronted with those facts, the doctor asserted, should know to withhold further painkillers unless trained in addiction therapy. He made it clear that addiction is a condition separate from the pain for which an opioid is initially prescribed, and must be treated separately.

I also spoke with David’s doctors in Seattle, where he had moved following the intervention-that-wasn’t. They, too, had recognized the need to help David ease off the addictive painkillers.

David and his Seattle primary-care doctor had discussed alternatives to Percocet and other addictive meds, trying one and then another when the first did not provide relief. David also had a surgery consult to address his herniated discs and congenital back issues. It was obvious that, six months before he died, David was trying to right himself.

Then, however, the December holidays arrived, as well as David’s 30th birthday on Dec. 17, and with them another visit home to Salt Lake City—and another visit to trusted family physician Dr. Smith for more pain pills.

On Dec. 19, 2012, Dr. Smith prescribed David 90 tablets— not of 5-milligram Percocet, but of 20-milligram pure oxycodone. A loaded gun.

Sixteen hours later, with 13 of the 90 pills missing—consistent with David’s history of taking five pills at a time, three times a day—David was dead.

David had been out to dinner with friends Dec. 19 and, as the autopsy showed, had a small amount of alcohol in his bloodstream, equivalent to two glasses of wine.

Even with that and the oxycodone, David’s cellphone reveals that right before he died, he had very lucidly been texting Ashly. He sent her a picture of a purse, inquiring, “Do you want this? It’s small, the flaps close with magnets, you can put your ID picture-side out on the sideways flap, put your wallet in there, etc....”

Ashly answered with: “Yeah!! Thanks baby!!”

He must have died a short time after that, as when I found him, the red purse was still in his grasp.

According to the medical examiner, in these situations, the deceased likely goes to sleep and just stops breathing. As CNN medical correspondent Sanjay Gupta said during his interview with former President Clinton: “People who take pain or sleeping pills and drink a couple glasses of wine are playing Russian roulette.”

David certainly didn’t know that. And as Clinton said: “Look, no one thinks having a few beers and an Oxycontin is a good idea, but you also don’t expect to die.”

WHERE DO WE GO

FROM HERE

David was beloved for his creative talents, but also for his kindness and humility, his sparkle and giggle. Following his death, his Facebook page filled with literally hundreds of expressions of grief and love. Friends, fellow musicians, actors and others who knew him only peripherally but were nevertheless touched, wrote about him: “I’d run into David every now and again, and the joy and depth and warmth he radiated was as beautiful a thing as has ever been produced. It is a rougher world without him. And another: “If creating beauty is hard, David made it look easy: He could do it on the back of an envelope, with a deck of cards, at the dinner table, in a song, on film, or onstage. To know David was to love more, and to merely see him was to feel better.”

I could copy hundreds of these and never capture the love David inspired in all of us, or the sorrow at his passing.

But while David is dead, others can be saved. Doctors’ excuses that patients cause their own deaths by ignoring instructions on the safe use of medications, or accusations that a deceased’s family members and friends could have intervened but didn’t, should be seen as just that: excuses. To suggest that it’s the fault of the addict, whose brain chemistry has literally been altered by the drug the doctor prescribed, is deflecting blame and contributing to the very shaming that makes it difficult for an addict to seek help in the first place. Now is not the time for excuses; it is a time for responsibility.

Prescription practices must be changed to acknowledge the addictive character of the drugs and the appropriate uses. Dr. Michael Von Korff, an epidemiologist in Seattle and a member of Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing, asserted in a Salt Lake Tribune article that “there’s no evidence these drugs are effective at managing chronic pain. ... These are treatments that should be used selectively, with great caution and at low doses.”

CODA

On Dec. 17, 2012, David turned 30 years old. In the birthday letter I wrote him, I said: “David, I can’t tell you how much I love you, and how proud I am of the life you’re living. You are a talented, honest, loving, considerate partner, brother, and son. How lucky I have been to be a part of your adventures! Here’s to a new era of growth in love and professional and creative successes. This decade you will do great things; of that I am certain.”

The David Ross Fetzer Foundation for Emerging Artists—or simply The Davey Foundation—was created in David’s honor to continue his work of promoting the innovative art of other young artists. It will be forever a testament to his vision, to his sense of responsibility to others and to his belief in community.

So many of us look to his example in hopes to live our lives with more purpose and more passion; to become better people. His death has robbed us of a lifetime of beautiful stories, plays, movies, music and humor. On April 7, 2013, David Ross Fetzer was nominated for Best Actor in the Victoria Texas Independent Film Festival, alongside Rutger Hauer (Blade Runner) and John Hawkes (The Sessions). He would have been honored had he known.

Beginnings and endings are important in stories and in life. I brought David into this world. I believe it was no accident that he returned to Salt Lake City—home—and it was here that he died. That I, his mother, was the first to see him after he had crossed that threshold; the first to hold him, not entirely cold; the first to cry for him.

And now it is left to me to tell the story of his life well lived, and of his tragic and unnecessary death, in the hopes that a doctor, or another David, or even an industry, will change course.

A TALENT PRESERVED

The David Ross Fetzer Foundation for Emerging Artists (The Davey Foundation) was created shortly after David’s death to honor his artistic vision and to provide the funding and mentoring necessary to help other artists pursue their creative dreams. Two grants will be awarded to playwrights and one to a filmmaker.

The first theatre grant will result in a private reading in spring 2014 as part of Plan-B’s Playwrights Lab and a public reading in summer 2014, leading to a full play production in early 2015 as part of Plan-B’s season. Scripts are being accepted now, with a submission deadline of Jan. 31, 2014.

The second theatre grant is for a weeklong mentoring with professional actors and directors in conjunction with Salt Lake Acting Company and an opportunity to further develop the chosen script, culminating in a reading on a SLAC stage in August 2015 as part of SLAC’s 2015 staged play productions. Submissions will be accepted beginning Sept. 15, 2014.

The film grant will consist of a monetary award to a filmmaker to go toward the completion of a short film that will premiere in Salt Lake City in December 2014. Calls for submission will go out Jan. 15, 2014.

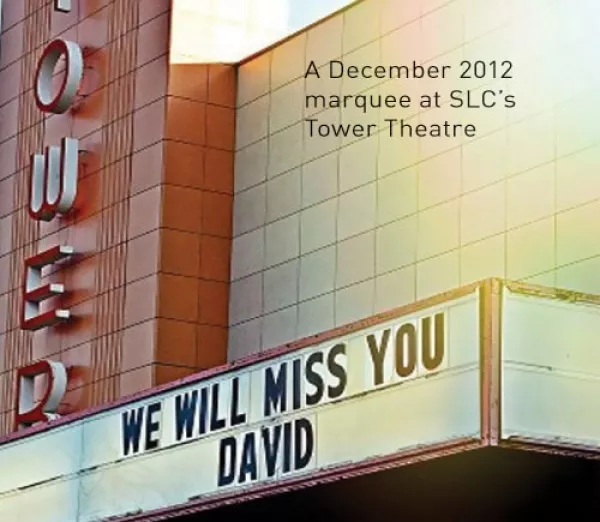

The foundation’s kickoff and fundraiser will be held Dec. 17, 2013, 7 to 9 p.m., at the Tower Theatre (876 E. 900 South). Tickets and more information can be found at TheDaveyFoundation.org.

Betsy Ross is a Salt Lake City attorney and writer.