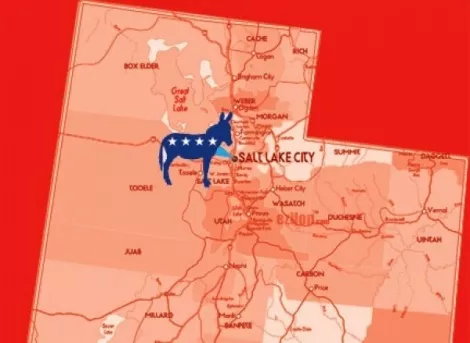

As the Legislature struggles to finalize the congressional map that will guide Utahns’ selection of their congressional delegates for the next decade, Democrats are bracing for a map that will hit them where it hurts—right in the liberal stronghold of Salt Lake County. A Republican “pizza” plan that would divide Utah’s urban, liberal core and combine the slices with more conservative rural swaths of the state is on the menu and is likely to be approved when the Legislature holds a special session Oct. 17.

In the meantime, state party leaders like Utah State Democratic Party Chair James Dabakis can make some noise about the map he says is motivated by “raw, political power.” And, if redistricting will hurt Democrats, Dabakis hopes exposing the backroom dealings of the process will hurt the state’s GOP power elites in the 2012 election and give power back to the people.

“What we’re hoping to do is expose this,” Dabakis says, “and get some of that lingering resentment to this corrupt process, to help, for example, the people of Utah uniting behind Jim Matheson for governor or for Congress in saying that political-party bosses don’t get to decide everything in this state.”

But Utah House Speaker Becky Lockhart, R-Provo, who also sits on the Redistricting Committee, says it takes two to play the politics card.

“Redistricting in all states is very political,” Lockhart says. “No matter which one is in power, [the opposing party] always tries to make it some sort of election issue.”

Every 10 years, after the latest census is released, state legislatures are tasked with redrawing equal voting districts that will guide citizens in picking their elected leaders—from school-board members to federal delegates who represent them in the U.S. Congress. With the 2010 census giving Utah a fourth congressional district, the mapmakers of the committee approached the congressional redistricting ready for a fight.

Unlike other more technical, complex maps demarcating Senate and House districts, the dividing lines on a congressional map much more clearly show how they divide not only cities and counties, but also Republican and Democratic strongholds.

Democrats say the Republican maps that slice Utah in districts that combine urban and rural areas are blatantly gerrymandered—divided so as to weaken the voice of the minority party, as when the traditionally liberal Salt Lake City Avenues neighborhood is in the same congressional voting district as Panguitch, in south central Utah.

The latest congressional map the committee favors puts Salt Lake City in a district that encompasses nearly all of western and southern Utah while also dividing Salt Lake County into three slices.

Republicans have said that they want federal delegates to be versed in all of Utah’s issues, especially public-lands issues.

“Children in Salt Lake City receive a lot less money for their education because the federal government in our rural areas doesn’t allow access to develop these lands, particularly [Bureau of Land Management] lands,” Redistricting Committee Chair Ken Sumison, R-American Fork, said in a previous meeting.

Dabakis, however, sees that as a thin excuse for a map designed to weaken the chances that Rep. Jim Matheson, Utah’s lone Democratic congressman, can be re-elected. That’s why Dabakis has already threatened a lawsuit against the Legislature for disenfranchising Utah voters.

Lockhart criticized this challenge as having a chilling effect on the committee’s ability to deliberate.

“The most disappointing part about it is that it makes it very clear they weren’t interested in allowing the process to move forward,” Lockhart says of the lawsuit idea, which was floated before the committee had finished picking a final map. “They had made their judgment about the outcome before it even started.”

Dabakis lobs a similar complaint against the Legislature, pointing out the drama surrounding the late-night Oct. 4 caucus meeting, where media accounts reported that the redistricting committee’s congressional map was stalled as some House members discussed the desire to make sure all the districts were at least 62 percent Republican.

In an Oct. 7 meeting of the Redistricting Committee, Sen. Ben McAdams, D-Salt Lake City, challenged Rep. Don Ipson, R-St. George, about such partisan calculations at the secret meeting.

“Numbers were discussed,” Ipson said. “But those weren’t the driving factors.”

Lockhart, likewise, says that map rewrites discussed during that meeting were postponed for approval since they needed to get more public input. Dabakis, however, says that if it weren’t for Democrat legislators rallying against the secretive meeting, they would have passed a map of their own, secretly crafted in the dark of night.

“[Republicans] were ready to ditch six months of work ... all that public input, and just go in that smoke-filled room and decide the map themselves,” Dabakis says. He says a flash mob took to the Hill in protest, and concerned citizens even recorded GOP legislators’ conversations as they walked from the caucus room to the bathroom. That sudden pressure, he says, forced the legislators to hold further public hearings. Dabakis says, however, that the added hearings are a farce and that Republicans have already made up their minds.

“It isn’t to get more public input,” Dabakis says. “The deal is done; this is just to justify what they’ve already done.”

Dabakis says these shenanigans will haunt Republicans at the 2012 election.

Tim Chambless, a professor of political science at the University of Utah, says there are some challenges to mobilizing voters behind questions of political corruption. The first problem is redistricting.

“Very few people understand it,” Chambless says. “If they studied it in school, they’ve forgotten it.” The other issue, he says, is that concerns of corruption tend to bring more active members of both parties out to the polls, but will often make moderate voters disgusted enough with the process that they don’t vote.

Ironically, he says, this correlates directly to past redistricting efforts.

“If you go back 30 years, 80 percent of registered voters voted in the state,” Chambless says. “[Now, voters] are disheartened and angry; they don’t even make voting a priority.”

But the public has mobilized recently to turn the political tide against doing away with Utah’s open-records law. After House Bill 477 was rushed through the 2011 Legislature in a manner of days, an overwhelming public outcry against the quietly crafted bill forced its repeal. But Chambless says the thing that united the public, from progressives to tea partiers, in fighting HB477 was the lack of public input on that bill.

Redistricting, however, has had months’ worth of public hearings. Committee members may not heed all that they heard in the meetings, but there was at least transparency—or the appearance of it.

“This time there is a smoke screen of a public process,” Chambless says. It remains to be seen if Democrats can play up suspicious closed-door meetings to voters, but it could resonate if done right.

“People are angry when they see their government being sneaky,” Chambless says.