Affordable homes, star-filled skies and fresh air aplenty: That was the draw for 22,000 nice folks who decided to make their homes in Utah County’s Eagle Mountain. Here, you’ll find the good life, residents say. It’s also the town that saw 10 mayors in 13 years, a turnover rate not unlike that of the graveyard shift at Denny’s.

“I don’t know why,” says Bonnie Floyd, getting her hair trimmed at the Eagle Mountain Great Clips. “I guess they picked the wrong people.” Her stylist, Kestin Powell, agrees the charm of the city is in its niceness but couldn’t guess what the political trouble was all about. “I vote, and I try and keep up on the issues, but I don’t get that involved with it,” she says.

Some of those who did get involved, though, found themselves pulled into a political machine that ground them up and spit them out of the community entirely. One mayor buckled under the pressure of negotiations with developers and took a white-knuckle road trip for 14 hours straight to Barstow, Calif., later reporting he had been kidnapped. Another mayor, Brian Olsen, is now suing the city for being falsely accused of embezzlement. Olsen says he was forced to resign from his post when two council members, including current Eagle Mountain councilman David Lifferth and former councilman (now Republican state senator) Mark Madsen took him from his house to a local developer’s office and told him the impending felony charges would ruin him. Olsen says he was told to wear a bulletproof vest, and that his family would be in danger.

Remove the pressure cooker of small-town politics, and Eagle Mountain is a close-knit community, close to wide open spaces and recreational opportunities: There’s the town’s new volunteer-built mountain-bike park, while great four-wheeling is just a short drive west at Cedar Fort. And, only 10 miles away, is an afternoon of boating at Utah Lake.

Ben Anderson, a 19-year-old clerk at Eagle Mountain’s Village Pizza, has lived in Eagle Mountain for 10 years, back when the jackrabbits outnumbered the people. “We’ve had a lot of mayors, but it’s still a great town.”

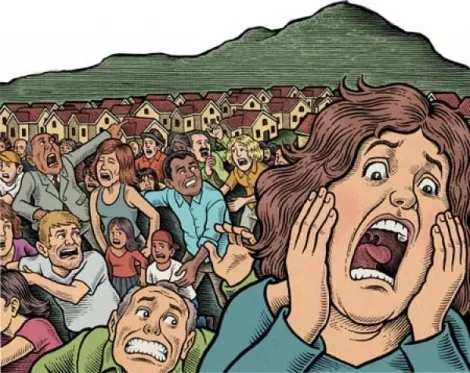

A great town, with a tumultuous past. Eagle Mountain’s history includes tales of officials receiving middle-of-thenight death threats, city hall meetings that nearly broke out in riots and one developer who, some claim, wielded so much power he helped orchestrate felony charges being filed against a councilwoman who disagreed with his interests. These charges filed against former Councilwoman Linn Strouse were dropped by Utah County prosecutors but not before the scandal helped undo her election bid.

Another former councilman, Greg Kehl, who constantly battled development pressure on the council as well as dark bouts of depression, took off one September day in 2007 in a powered parachute. Flying high above Cedar Valley, Kehl took in the eagle-eye perspective of the community one last time, and in mid-air, put a gun to his head and ended his life.

Caught between small-town values and bizarre scandals, the geography of Eagle Mountain is hard to place: Is this Anytown, USA? Or is this The Twilight Zone?

A number of Eagle Mountain refugees, dispersed across the state and nation, are convinced that one developer in particular, John Walden, cast a long shadow over Eagle Mountain. As in one episode of that 1960s TV series, in which a 6-year-old boy controls a small town by reading the thoughts of its citizens—forcing them to think happy thoughts to avoid their own destruction, some accuse this developer of similarly manipulating Eagle Mountain residents to accede to his demands.

In the episode, after the mind-reading boy turns a man who yells at him into a Jack-in-the-box, residents try to block the horror from their minds, cheering on their boy-monster: “That was a real good thing you did, a real good thing!”

For those who struggled with the politics of Eagle Mountain, their monster was John Walden. From his alleged sponsoring of shill candidates for city posts to helping get charges filed against those who disagreed with him, Walden’s influence on Eagle Mountain municipal politics was hard to ignore, as the litany of overworked and burntout elected officials would suggest. But, while others see his notoriety as more imagined than real, critics maintain he ruled Eagle Mountain, and anyone who didn’t think “happy thoughts” around him did so at their own peril.

Eleventh Hour Antic

From a May 22, 2000, Salt Lake Tribune article: “In 1995, Florida businessman John Walden ascended a steep slope, gazed out at the sagebrush and jackrabbits in the Cedar Valley below and, like a latter-day Brigham Young, proclaimed, ‘This is the place I will build my city.’”

In 1995, Walden indeed looked out at miles of a west desert valley and did see something—but it wasn’t a city, not at first. With development interests in the Heber Valley, Walden planned to transfer water rights from the Cedar Valley land he had purchased in a foreclosure sale to his Heber Valley holdings. Misunderstanding water-rights law, however, Walden soon found himself the proud owner of thousands of acres of sage and dry dirt.

Walden mastered the art of the deal through his many ventures back in Brevard County, Fla., including an auto dealership, a mortgage company and an eye-care business. It was through eye care that he made contact with doctors Scott Gettings and Andrew Zorbis, who were regular snowbirds to Park City, Utah. The doctors helped convince Walden that Heber Valley offered prime real estate in which to develop a community. But when Walden realized he and his investors’ water rights were locked into the Cedar Valley, Walden decided to develop the town that would be Eagle Mountain. Backed with Walden and his investors’ greenbacks, the city’s business became a key focus of Walden’s.

“He called me Satan once,” recalls Debbie Hooge, the original mayor of Eagle Mountain, appointed by the county in 1996 until formal elections could be held, when the city was first incorporated.

According to Utah

County Commission meeting minutes from November 1996, Walden

representatives assured county commissioners the city would not become

a burden to the county. This was because Walden agreed to front the

costly expense of bringing utilities out to the isolated city. This

helped persuade the commission to approve the town’s incorporation.

According

to city records, however, as soon as incorporation was granted, Walden

backed off from his offer to pay for the utilities. Walden’s new deal

was to help the city temporarily bond for the utilities by using more

than $11 million worth of his land as collateral.

“When we did

the first bonding for the utilities, I walked into the [city]

attorney’s office and there was a table, probably 15 feet long, full of

documents,” Hooge says. As mayor, she began signing the documents for

city attorney Gerald Kinghorn. Then, she says, Walden arrived and

passed a document to her and Kinghorn, telling them that, as guarantor,

he wouldn’t sign the bonds until the city signed his agreement—an

agreement that encumbered the city for almost all of Walden’s Eagle

Mountain Properties company expenses, from utility bills to even the

land his company was headquartered on.

“I turned to Kinghorn,

and he said, ‘Debbie, if you walk out of this bonding right now,

everyone [planning on] buying the bonds—they’re going to sue the

city,’” Hooge recalls. The 11th-hour antic worked for Walden, although

Hooge says Kinghorn was able to amend Walden’s agreement to let them

negotiate components of the deal. Still, she says, he squeezed a lot

out of the tactic. “That was just life in the city with him,” she says.

On good days,

many saw in Walden a jovial man. With his heavy frame, white beard and

beaming smile, former Mayor Brian Olsen often saw Walden as a jolly

Santa Claus figure. Add to this a surfer’s ponytail and a soft cooing

voice that sounds about as intimidating as Bill Murray in Caddyshack, and you have John Walden on his good days.

But,

on his bad days, “there were a couple times he threatened physical

violence,” says former Councilman Brigham Morgan, recalling a typical

Walden tantrum. “He would get angry, he would get flustery, he would

get right in your face.”

According

to Morgan, Walden’s tirades were peppered with angry talk, reminders to

those present that he packed a pistol in his briefcase, and more

importantly, that it was his millions that guaranteed the city’s

existence.

“His presence was always there,” says former Councilwoman Diane Jacob. “You could feel it even if he wasn’t there.”

Former Councilman Vincent Liddiard remembers Walden’s theatrics but felt the infamy of Walden was overblown. “John’s ability to bear sway was directly proportional to the population of the city,” Liddiard says. “As the population has grown, his power has diminished,” he says.

In October 1999, Walden notoriously threatened to pull all stakes out

of the then-fledgling community and take his money elsewhere if the

city did not reduce its impact fees— the fees new homebuyers pay to

help defray the costs of providing town infrastructure and services to

fellow residents. According to an Oct. 25, 1999, Deseret News article,

then- Mayor Rob Bateman balked at the threat, saying Walden already

owed the city $400,000 for promised investments in trails, land and

past due bills. But when the showdown ended, impact fees were cut in

half.

Walden

had achieved so much leverage, former officials say, because the city

had racked up debt buying all its utilities after Walden reneged on his

company’s offer to buy them. Impact fees through home sales were the

only way city officials could keep the city afloat.

Brigham

Morgan, a former Eagle Mountain city councilman and planning commission

member, says it’s unusual for a new city to eat all the debt for

utilities. “You go to any other city, and developers have to pay to get

the utilities to their lot,” Morgan says, citing Eagle Mountain’s

neighbor, Saratoga Springs.

According to Saratoga Springs City

Manager Ken Leetham, while Saratoga Springs didn’t buy its own electric

or natural gas utilities, the city has only incurred $5 million in

water-system bond debt in 2005. By comparison, that same year, Eagle

Mountain still had just over $45 million in total utilities debt,

according to city records.