“I was about to freeze to death,” the wiry Bartlett recalls, “and I knew with a 100 percent certainty whatever was taking care of that calf that night would keep me sober.”

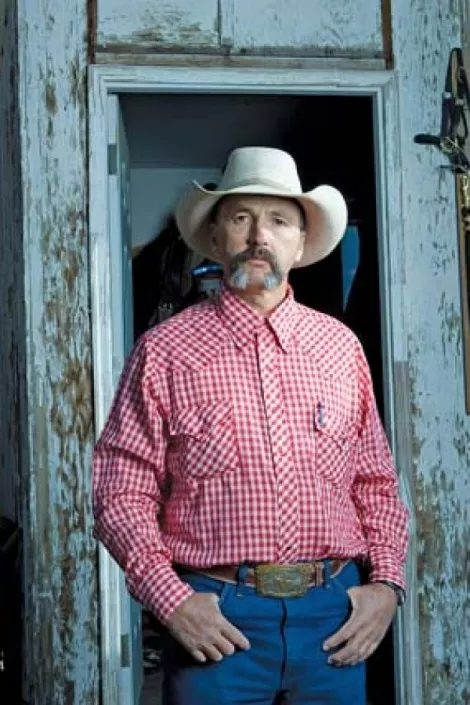

That was more than 20 years ago, shortly before Bartlett stopped drinking for good. A few years later, in 1995, the now 50-year-old recovering alcoholic with a telltale blueberry-black chew stain on his lower lip got the job “I’d wanted my whole life”—caring through the summer for 944 cows and their calves belonging to 10 members of the Springville Livestock Association.

For 12 years, Bartlett’s routine never wavered. Every May 15, he mounted his horse and began preparing the 55,000 Forest Service-supervised acres of Hobble Creek canyon, on the edge of Springville in Utah County, for the cattle. He’d trim back growth from trails, fix troughs, and lay down salt blocks across the ridges to control grazing. “The better you are at putting the salt out, the better the range is utilized,” Bartlett says.

Drawn by the salt, the cattle graze up the hill, lick the reddish-brown bricks and, thirsty, graze back down the hill to a nearby stream. On June 10, Bartlett started trailing them up into the mountains, cared for and doctored them. At the beginning of August, he moved them from one of the three allotments they were allowed to graze on to a second. In October, he trailed them back down to their owners.

But, on May 14, 2007, Bartlett suddenly had desperate need of whatever spiritual force he found up in the mountains that cold winter night the calf was born. That was the day he quit the job he wants back as badly as the 19-years-sober alcoholic still wants a drink.

“There’s far more to the job than just playing cowboy,” the 50-year-old Bartlett says. Along with being a horseman, he’s a cowman, a forester, a veterinarian and a weatherman. “I am a prideful, egotistical bastard to a fault,” he says. “If I’m going to do a job, I want to get it done right, perfect.”

So when Springville Livestock Association president Craig Sumsion told him to delay putting out the salt blocks as he’d done for over a decade and help with fencing instead, Bartlett refused. Sumsion did not return calls to City Weekly for comment.

“Craig, I ain’t never had to put up fences,” Bartlett said. Indeed, it was a chore the grazing permittees did, Bartlett says, and was not in his contract.

Things were different now, Sumsion, owner of a trucking company and more than 100 head of cattle, told him. “The days of you going up there and doing what you think needs to be done are over and done with. I’ll call you every morning and tell you what to do,” Bartlett recalls Sumison telling him.

“I don’t think so, Jack,” Bartlett spat back.

The cattlemen met that evening. Bartlett went to his son’s baseball practice. His cell phone rang. They still wanted him to put up fences and put salt out at the beginning of June, cutting by two-thirds the time he dedicated to what he regarded as a key element of caring for the cattle.

Bartlett got a fresh can of Copenhagen, loaded up the association’s equipment and drove it to the association treasurer Justin Diamond’s house. “You sure you want to do this?” Diamond asked him.

“No, I’ve got no choice,” Bartlett recalls saying, almost in tears. “I’ve argued with these guys until I’m blue in the face. I’m not going to do it anymore.”

None of the permittees, many of whom count Bartlett as a friend, question his work. “He done a real good job,” Hobble Creek permittee George Hutchings says. Which just frustrates Bartlett all the more. If he was doing things right, why change? Permittees say they just couldn’t afford to pay him what he needed. So they hired 22-year-old sheepherder Gustavo Gomez for $900 a month and free board and lodging, Hutchings says. He did the fencing while the cattlemen did Bartlett’s job and trained the sheep man to eventually replace him. In June, Gomez returned for his second summer on Hobble Creek.

In 2007, Congress passed a bill banning domestic horse slaughtering. One consequence of that bill was the collapse in the value of horse meat in the U.S. Horse meat prices set a baseline for speculative horse purchases. Horse traders could no longer buy and sell horses, due to the cost of shipping the animals to Mexico or Canada to be killed. This was one more nail in the coffin of the cowboy way in Springville, and, in fact, across the entire country. In the last 18 months, central Utah’s two livestock auction houses, where Bartlett supplemented his meager Hobble Creek income selling horses, closed.

The auction barns were also victims of technology like Internet cattle sales. Bartlett, on the other hand, was caught between cheap immigrant labor and a new generation of cattle owners who’d rather enjoy the cowboy lifestyle—at least after hours—than employ and do battle with the real thing. He seems as much a casualty of his own exacting standards as his stubborn belief that over a decade on the mountains trailing cattle, makes him the indisputable authority on the land and stock that grazes there. Bartlett admits he’s a dinosaur, one of a dying breed. He’s also a symbol of a battle the West clings to, and never ceases to fight.

“Anybody who’s an honest-to-God true cowboy,” Bartlett says, “is always at the mercy of some farmer, rich man or cattle association.”