What do you get when you combine

the visual impact from the worlds

of advertising, children’s book

illustration and the flying fancy of a trained

fine-art eye? The work of David Habben.

Since last I interviewed him in 2006—

on the occasion of his show at PR firm

W Communications, while he was still

a senior at BYU—his style has not so

much changed but evolved. His experiences

in the meantime have added depth,

both figuratively and literally, to work

on display at Kayo Gallery (with Amber

Heaton and Claire Taylor, see Essentials

Weekend, p. 26).

While the 2006 show featured inventive

and whimsical takes on childlike illustrative

figures and mythical creatures, his new

work has a more-personal, highly pointed

symbolism, though not one that simply

directs the viewer to an inevitable interpretation.

From the “La-La Land” of the subconscious

in that former show, he’s moved to

images that seem ingrained on the cranium

in that space of time where you are just

awake enough to have to crane your neck to

view it and be able to take everything in.

Since graduating from BYU, Habben

(pronounced with a short “a”) worked at

Struck ad agency in Salt Lake City, then

Chronicle Books in San Francisco for eight

months, then returned here to pursue freelance

illustrating. While in San Francisco,

he mounted two shows that completely sold

out. Recently, he’s been

designing skateboards

for Worship Skateboards

in Connecticut. “My commercial

work gave me a

strong grasp on the digital

process,” he explains,

“much more education

than at school.”

Instead of sketching

images by hand, he now

uses a Wacom tablet, a

digital pad that transfers

impressions from a

stylus onto a computer:

“It’s pressure-sensitive,

so I can create different

shadings.”

Removing the “hands-on” approach has helped enable him to construct much more personal works of art. These pieces are also 3-D, with sections cut out and raised with segments of foam core, suggesting a route around the work without dictating a definitive pathway.

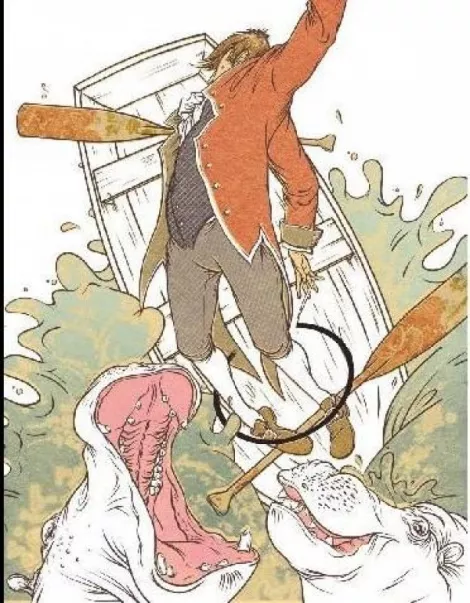

In “Overboard,” lower left, a man in a boat with oars leaps out of the water to escape the jaws of twin hippos. Another lends an aerial view of a series of men in business suits on a tightrope. Several of them seem to suggest religious symbolism, like one (above right) with a lion biting a snake biting a man in a white robe, with the hand of an angel reaching down to him. A completely personal Habben detail is the inclusion of two patterns: a flower pattern he got from his grandmother’s pillowcase and a check pattern from a tie that he and his father each owned one of. These patterns. he says, suggest the strong role of the guidance of family figures.

“It’s been a challenge to be an

LDS artist,” he admits. “We are

supposed to be ambassadors for

our faith, but an artist approaches

things differently, not with direct

teachings like pictures of pioneers,

but something more indirect.”

In a piece that could be taken as some kind of historical commentary, a cowboy riding a horse is shot with an arrow, and a American Indian headdress flies off his head. In the only one with an overt connection to his Mormon faith, a group led by a robed figure—which Habben explains is Book of Mormon character Alma the Younger—is confronted by an angel. “He’s explored the world and is now being called back to change his ways,” Habben explains. His visual explorations haven’t seemed to bring him into conflict with his own religion, although they have led him to ponder and reflect on aspects of it.

One figure in another work with a

Roman-looking garland on his head,

Habben explains, comes from a folktale in

which a boy asks his grandfather how to

be a good person. The grandfather tells a

story that we all have two wolves inside us,

good and bad, which battle it out. In a bit

of irony, the more benign-seeming one is

at the Roman figure’s side, while the man’s

hand reaches behind him to pass the “bad”

one a piece of meat. “It refers to Plato’s

idea of what makes a good, moral society,”

Habben explains, about acknowledging

the darker side of human nature and not

trying to eliminate it, since that would be

impossible, but rather to keep it in check.

There is, it seems, that dualit y in

Habben’s work—depictions of danger,

creatures presenting perils both mythical

and real, and the protagonists’ struggles

to not so much conquer one but

strike a balance between elements that

persist in the human character. It’s fascinating

that Habben is able to explore

them visually, yet not be taken in or

devoured by the danger. He is like one of

the tightrope walkers, and it is a delicate

exercise to witness.

DAVID HABBEN

Kayo Gallery

177 E. Broadway

Through Aug. 18

801-532-0080

KayoGallery.com