Sources say the victim had “snitched” on the aggressor.

A not-so-unusual occurrence in prison, right?

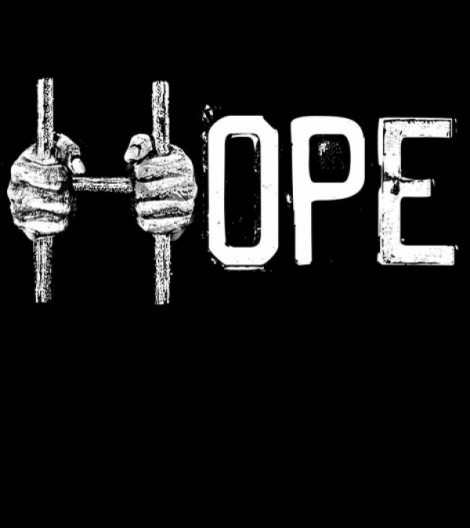

Perhaps, but this assault didn’t just take place in prison. It happened in a “therapeutic community,” the drug-rehab program called HOPE (Helping Offenders Parole Effectively). The aggressor in the fight allegedly was a “positive peer leader” in the program, and his victim was a newcomer still learning the rules.

HOPE offers inmates the chance to turn their lives around if they follow program rules. The rules can be as mundane as washing one’s hands and making beds to the more consequential ones of failing to report inmates who don’t follow rules. In common prison lingo, inmates are required to snitch on one another, every day.

Ironically, the inmate who received the 10-minute beating last June was assaulted, sources say, because he followed HOPE rules and snitched.

Since the community is expected to police itself, when things go wrong, they do so with dire results. Take one instance, when the HOPE community — along with prison staff and cameras — failed to notice when one inmate, Joe Manuel Alires, took his life.

Utah Prison Inmates Snitch at Their Own Risk

The HOPE program faces unique challenges. First and foremost, HOPE is a treatment community, a criminal fraternity that struggles to exist within a prison that houses as many as 1,500 offenders, from sexual predators to gang-bangers to murderers. The prison culture is violently hostile toward snitching. It’s also a culture of offenders who know how to game a system — even one as well intentioned as the HOPE program.

Defenders of HOPE view it as a life-changing experience and possibly one of the most sophisticated drug-treatment programs in Utah’s prison system. It also operates with little accountability, as the Utah Department of Corrections has not evaluated the effectiveness of the program in its 10-year existence beyond anecdotal successes.

In the home of Roy Alires, father of the late inmate Joe Alires, two portraits contrast each other. In one photo framed on a wall, Joe, wearing diapers, is riding a toy bike and grinning ear to ear. On top of the TV, another photo shows Joe before his death: 34 years old; shaved head; sporting a mustache, a gold cross necklace and a weary look in his eyes. When asked about the HOPE program, Roy Alires doesn’t hesitate in his estimation of the program.

“There’s no hope down there,” he says.

God is Truthful

Probably the last place a black, Orthodox Muslim from South Chicago might expect to find himself is the Central Utah Correctional Facility in Gunnison. But for 39-year-old Larry Agee, CUCF has been home for the past two years and will be for at least five more while he finishes an armed-robbery sentence for holding up a North Salt Lake dope house in 1999.

At 6 feet 9 inches tall and 270 pounds, Agee doesn’t worry too much about watching his back in prison. Like many inmates, Agee’s arms are inked with tattoos: On one forearm, neat Arabic script reads, “God is merciful and just”; the other forearm bears the characters for “God is truthful.” But unlike many inmates, Agee spends much of his time learning about the system that’s claimed the past decade of his life. He knows Utah’s Government Records Access and Management Act inside and out and has used it to spar with prison administration on more than one occasion.

“The HOPE program, for which I spent 13 months in, is the standing symbol for an intense pressure that is doing inmates more harm than good,” Agee writes in an August 2009 letter to City Weekly. “At the HOPE program, inmates are being assaulted by other inmates, they’re attempting and succeeding at taking their own lives and others are learning how to become better predators and manipulators, all because of the HOPE program’s irresponsible, thoughtless and downright dangerous approach to drug rehab.”

Agee was aware of the suicide of Joe Alires, since Agee promoted Alires to the level of junior mentor the day before Alires took his life on Aug. 4, 2009.

In the HOPE program, inmates rely on a small clinical staff and their fellow inmates to take care of them, and while Agee says no one really could have known Alires would take his life that day, he says there were signs he was depressed.

“We’re in a program with lettered psychologists and psychiatrists, section coordinators—all these people see these things, but the staff is just so out of touch,” Agee says. “You could have asked any of the inmates, and they would have told you, ‘Yeah, the dude was pretty morose.’” Alires was progressing in the program, but he was also allegedly distraught over personal issues relating to his family in Salt Lake City, Agee says. On the day Alires took his life, a group of roughly 20 inmates were seated in a HOPE class looking out a window into a small recreation yard. The yard was empty except for Alires. When the instructor of the course called for “open library,” the inmates rose from their chairs and began milling through carts for books to read. During this time when inmates were distracted, Agee says, Alires lifted the tarp covering a large piece of exercise equipment, crawled underneath and hanged himself from the bars of the machine.

Not all take Alires’ route out of HOPE; many simply play the game. With the HOPE program investing trust and even power into the hands of inmates who advance in the program, Agee describes it operating like a political machine behind bars, where senior mentors allegedly bring their friends and fellow gang members up for promotion while dispensing punishments to inmates they don´t like.

The HOPE program elite play politics while the few available staff disengage, expecting the community to police itself, Agee says. He alleges that is how one inmate came to be beaten bloody for nearly 10 minutes before help arrived.

“They [the staff] were expecting someone to push the button,” Agee says. “They expect inmates to be on cruise control.”

Mind Your P.B.L.s

“This

is the best treatment freedom can buy,” says Clark Holladay, HOPE

program director based out of Gunnison. “Because that’s what you pay

for it with.” With decades of experience in counseling and social work,

Holladay is a veteran of the drug-treatment industry, having previously

worked for outpatient drug rehab facilities like LDS Hospital’s

Dayspring program. Holladay is a man with the calm, soft-spoken

demeanor of a lifelong therapist. He’s also one who appreciates the

opportunity that HOPE offers inmates. Holladay recalls his past rehab

experience, assisting with Corrections’ Adult Probations and Parole,

when he felt as if he were merely “documenting noncompliance.”

“We were pariahs,” Lane Porter says, “We were seen as cops,” adding that members of his section faced added security risks for their participation in the program.

But with in-prison treatment, Holladay says, there is a great opportunity to reach addicts using institutional rules to coax participation. Using the program’s “stick” of enforcement, the prison can send inmates who refuse to participate in HOPE to solitary confinement in CUCF’s discipline block for as long as four months.

But that’s not to say there isn’t also a carrot involved, as well: HOPE inmates usually have an edge in getting transfered to desirable prison programs, like the horse-gentling program that allow inmates the chance to work outdoors. HOPE graduates also generally win points with the Board of Pardons that may shave a few months off their sentences. HOPE peer leaders enjoy the benefits of luxury items like recreational movies, video games and the chance to buy items such as sneakers from mail-order catalogs.

The program is designed to correct criminal thinking. As a result, a common punishment inmates face for not owning up to a mistake is called an “image-breaker,” similar to a one-man skit. It could mean an inmate would have to sing “The Teapot Song” (“I’m a little teapot”) in front of their fellow HOPEsters, sizzle like bacon, or pretend to be a wild orangutan for 30 seconds.

“It’s kind of a way for the guys to break down their con-code mentality, because they can be silly with each other and the community claps for them and cheers them on,” Holladay says.

The punishments result from infractions of HOPE rules, which go well beyond regular institutional rules. Those rules include everything from being punctual to not using restricted words, or PBLs, which stand for “punk,” “bitch” and “lame.”

For inmates in the program, there is a ladder of leadership roles. The goal is to progress up the rungs, from crew member to crew boss to junior mentor and, perhaps, a paid senior mentor.