Heaps slammed into a chair, his gun flying out of his hand, even as the suspect wielded a pair of scissors, cutting Heaps’ forearm and hand. As Heaps dove toward the man, the suspect retrieved the officer’s gun, and Heaps found himself staring down the black hole of his own .380. The suspect fired, the shot, Heaps says now, zipping harmlessly through his hair.

Even as he grappled with the man, he shouted out at then-fellow vice officer Shawn Josephson, “Just fucking shoot the guy.” As Heaps pulled himself up from the suspect, he saw three “perfect holes” in the man’s side, “a big hunk of his love handle on my pants.” He and the other officers watched the man “take his last five breaths.”

A man who openly admits to a hefty sense of pride, Heaps says he didn’t weep or have nightmares like some officers have after a shooting. Josephson, however, recalls that Heaps was watchful over him in the following days, concerned about his psychological well-being. “He’s a tough guy, he didn’t like to show that side of himself,” Josephson says. The night of the motel shooting, however, Heaps should have been more concerned about his own standing in the department.

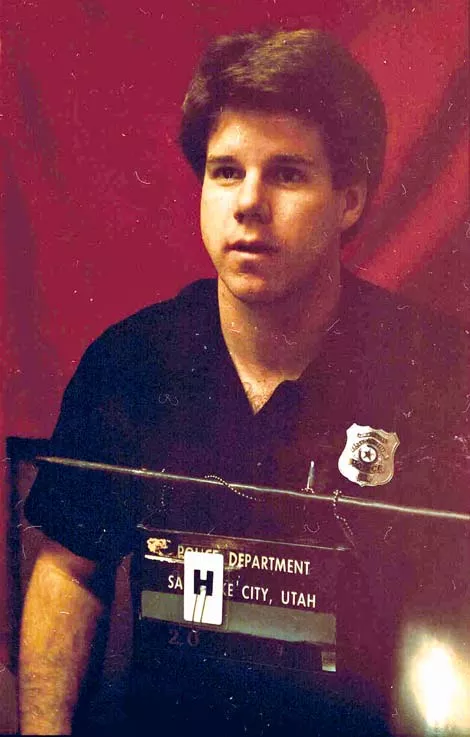

Although Heaps, then an undercover vice detective, was neither the lead nor the senior officer on the attempted arrest, he was the one who led the assault after the drug dealer had fled from an undercover female officer in the middle of a drug deal. As a vice officer, his job, for the most part, was arresting prostitutes, but he had taken part in the drug bust to help out fellow officers. The two senior female officers and Josephson had only one interview each with Internal Affairs, but Heaps, by then an eight-year veteran, had five. When he questioned why so many, he was told he was the de facto leader. “They didn’t like the shooting, but they couldn’t lay anything on me technically,” he says in his growly, rasping tones.

For the first 11 years of his career, Heaps was a “street monster,” he says, a term he borrows from author Joseph Wambaugh to describe officers who are effective in a fight and typically take control of dangerous situations when other, less experienced—or, Heaps argues, incompetent—colleagues fail to do so. “Street monsters do the dirty work,” he says. His approach in his first years caused problems. He had several force complaints held up against him in 1990. But after 1990 such complaints “quit coming; he changed his way of doing business,” recalls Deputy Chief Lee Dobrowolski.

Heaps “looked like a brute, but he’s very intellectual, very eloquent,” says Dobrowolski, who for many years was Heaps’ best friend. They worked together on the graveyard shift and would park car to car and talk in the early hours about their shared passion for music and the arts. Music is a passion Heaps now explores as a volunteer blogger on CityWeekly.net. “His size intimidated a lot of people and then he spoke with a passion that intimidated them a lot more,” Dobrowolski says.

When Heaps retired from the Salt Lake City Police Department [SLCPD] on Sept. 1, 2008, he was a bitter, self-described functioning alcoholic with chronic-pain issues from a lower-spine surgery. His heavy drinking started after a year in vice. “Part of the problem with Lane was he keeps everything in,” says Sgt. Merrill Stuck, who served with Heaps on the graveyard shift for many years. Then, like many cops who struggle with witnessing trauma, “he tried to drink it away.”

Currently, Heaps takes eight medications a day and wears synthetic heroin patches that offer no euphoria. “Just half the drugs I have in me would kill the average person,” he says. Yet the pain is barely eased and every third day becomes unbearable. “When it gets too heavy, I panic, I don’t know what to do with it.” Morning or night, he self-medicates, pouring with a shaking hand tumblers of rot-gut whiskey to take the edge off the pain, his anxiety and depression. “Pain, loneliness, those scary things,” he says. “They’re all they are cracked up to be.”

He believes his spinal issues may well have stemmed from years of twisting in his patrol car to type one-fingered on the computer. But the anger that gnaws at him about his treatment by the police department, notably in his 1999 trial and subsequent acquittal for the alleged assault of a handcuffed DUI suspect in March that year, seems even more corrosive than the daily agony that keeps him awake into the early hours.

Heaps grew up steeped in the old-school police culture of his father, Willard, who rose to assistant chief of the Salt Lake City Police Department before retiring the day his son joined the force in 1988, and the memory of his uncle, Sgt. Ronald L. Heaps, who was shot to death in 1982 during a routine investigation. But in contrast to the tough-guy cops who skirt civil rights to get the bad guy in prime-time dramas like NYPD Blue and Blue Bloods, the colliding realities of urban policing and department politics ended up devouring not only Heaps’ career but his life.

Heaps’ story provides a visceral insight not only into the nature of policing Salt Lake City but also into the toll the profession exacts on some of its workers. With long-term anxiety issues, agoraphobia—a fear of being in places you can’t leave—and clinically diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder from his police work, Heaps, self-medicating with alcohol and copious amounts of prescription drugs, was arguably already an officer on the brink. That he also felt railroaded by the very department he had given his life to for so many years, “threw him into a horrible, wicked spiral,” SLCPD Lt. David Cracroft says, which he has yet to come out of.

Sgt. Josephson credits Heaps and another officer-cum-friend who killed himself with providing the impetus for him to set up and run a peer-support program to the department 10 years ago. It’s a need that continues to be pressing. “Everyone in law enforcement knows someone like Lane Heaps,” Dobrowolski says.

On Feb. 3, Heaps turned 50. Retired from the force, without work, he sits in a one-bedroom apartment in Murray, his back cushioned by pillows, his feet up on a stool, trying to reduce the constant “sledgehammer” burning he feels in his feet. “He’s still barely not drowning,” says SLCPD Sgt. Roslyn Rainey, his soon-to-be second ex-wife, whom he married in 1996. After all these years, he still seethes over his treatment by former superiors, who have long since moved on after sanctioning his prosecution by the District Attorney’s Office. “The motherfuckers who came after me weren’t touched, not even a little bit, making it impossible for me to heal, and leaving revenge fantasies always swirling in my head to this very fucking day,” he says. “Can you understand why I’m bitter?”

THE SMELL OF THE NIGHT

Lane’s father, Willard Heaps, now in his mid-70s, joined the Salt Lake City Police Department in 1959, when it had 350 officers. “At that time, if you were aggressive, you were at the top of the pile,” Willard says. The approach was to make criminals fear Salt Lake City Police, he continues. “It was rough and ugly, but it worked. If I stop you, I treat you like a man until you show me that you are not, then I’ll make a correction.” The administration over Willard Heaps sought officers “who took steps to get things done. People who went places were the guys who shot people.” But, he cautions, “You had to know when to slam somebody and when to back off.”

Lane Heaps joined the police on Sept. 1, 1988, the day his father retired as assistant police chief from the same department. Lane Heaps says he became a cop for the money and the health insurance. “It’s an easy job for me; I’ve never done anything better. It’s about common sense: You think quickly, coolly, and can’t pick wrong or you might be dead, in prison or have somebody else like me save your ass.”

He loved his first years, especially the summer nights on the graveyard shift, “when only the cops and the bad guys are around,” and you could get to the violence “while it’s still happening.” But he worked so many graveyard shifts, “I couldn’t smell the night anymore.” The constant barrage of negativity he experienced as a cop wore on him. “Everywhere you go, people were drunk, pissed off, fighting, you have to go in and referee that crap. After a few years, it starts to drag you down.”

The violence he saw was also difficult to absorb. A year into his service, Heaps witnessed something that he still struggles to understand. He and his partner received a call from dispatch to go to a man screaming at a small, rundown apartment complex on Park Street, close to Trolley Square. When he and his partner entered the ramshackle, “shithole apartment,” they encountered a 40-year-old woman lying on a bed, flip-flopping like a fish out of water, a wound in her head so large and deep they could see her brain. For several seconds, Heaps and his partner stood in disbelief, staring at the woman’s demise. It was something, Heaps says, “we couldn’t recognize, that simply couldn’t be. She was kind of like a zombie. It was one of the ugliest deaths I’ve ever seen.”

They took the woman’s boyfriend into custody and led the screaming man, her son, into another room. The woman had been caring for two boys, ages 6 and 8. The 8-year-old’s ear had been half-bitten off. The boy told the officers that it was the grown son who had bludgeoned his own mother, then raped her, in a fit of jealousy after she had shifted her sexual favors from him to her new boyfriend. The grown son had bitten the boy’s ear off as a threat to silence him.

Heaps witnessed “more than his fair share” of violence, Dobrowolski says. Sgt. Stuck says witnessing such crimes “really got to [Heaps].” Officers like Heaps “hold everything in, it eats away at them.”