Page 2 of 2

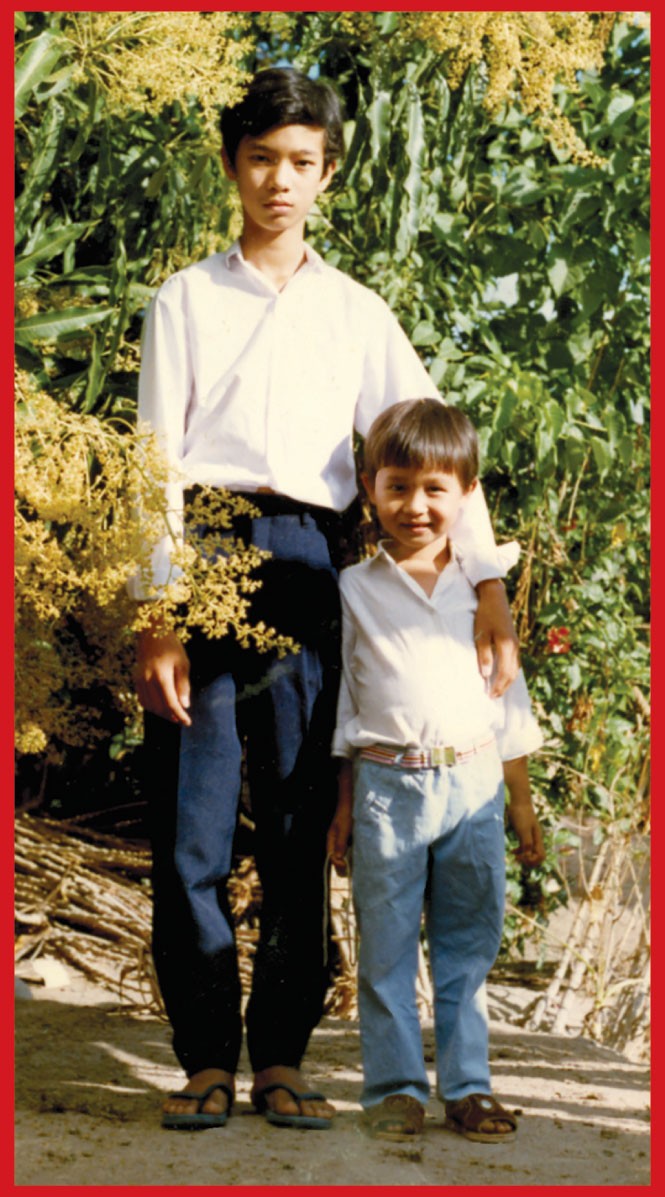

- Tam with his older brother in their village.

American = White

That said, I remember the first time I heard English in person. I was about 5 or 6, and we were in Saigon doing an interview with an immigration official. We sat in a dark office and the American sat behind a desk. To his right was a translator, who negotiated the questions between him and my parents. This was a Very Big Deal moment because of the body language and tone of everyone in the room. There was my dad with hat literally in hand, answering questions and avoiding direct eye contact. The translator spoke to the official with a hushed deference. I don't particularly recall my impressions about the language upon hearing it, but it registered with me that it was the language used to talk about important things.

When my family came to the United States in 1991, I was in the second grade. I knew three sentences that I strung together as a stock response: "How are you? I'm fine. I'm from Vietnam."

I remember being bombarded with questions from well-meaning teachers and I would respond, in rapid fire, those three sentences, no matter the situation. So, conversations probably sounded something like this:

"Hey, check out my rad marble collection!"

"How are you? I'm fine. I'm from Vietnam."

"I can tell those twins from Full House are gonna grow up to be just fine!"

"How are you? I'm fine. I'm from Vietnam."

My first day of school also had a scene that was so powerful to me that I used it in my job interview to explain why I became an English teacher. My uncle Frank, who was in the Air Force, was American. By the way, when Vietnamese people say "American," they always mean "white." He had married and brought over my aunt from Vietnam. On that first day of school, he walked my dad and me into my classroom.

I stood in a corner and watched the scene in front of me, and again, I saw just how much of a difference knowing English made. My uncle was comfortable, in control, conversing with his hands. My dad stood to the side, hands still, smiling a sheepish grin.

I don't think people always realize how important language mastery is when it comes to basic things like receiving dignified treatment from others. Both my parents are smart, passionate, complicated people who have smart, passionate, complicated thoughts. But when I sometimes see them engage with the English-speaking world, or see the way they sometimes fret over an opaquely worded policy, I see a look of helplessness.

What I mean by this is that sometimes when they're in a store or asking a question, or being seated in a restaurant, and they open their mouth to speak to take the time to come up with the word they mean, there is a look in the listener's eyes that tell me my mom or dad is at this moment a subhuman. I know this sounds dramatic. But it's something that bothers me all the time. We don't, as a culture, validate people based on who they are, but their perceived intelligence in our language.

This helplessness translates into the way my parents engage with the world, too. I've seen them fearful of advocating for themselves at work because they were terrified of losing their jobs. My mom used to work in a computer-chip factory and had developed carpal tunnel as a result of repeatedly squeezing a nozzle. She used to come home in tears sometimes, but she sucked it up and fought through the pain. I remember once, when I was 12 or 13, hearing my dad leave his boss a voice message asking if he could take the next day off. The servility in his voice, the pleading, the struggling to get out words, was painful to hear.

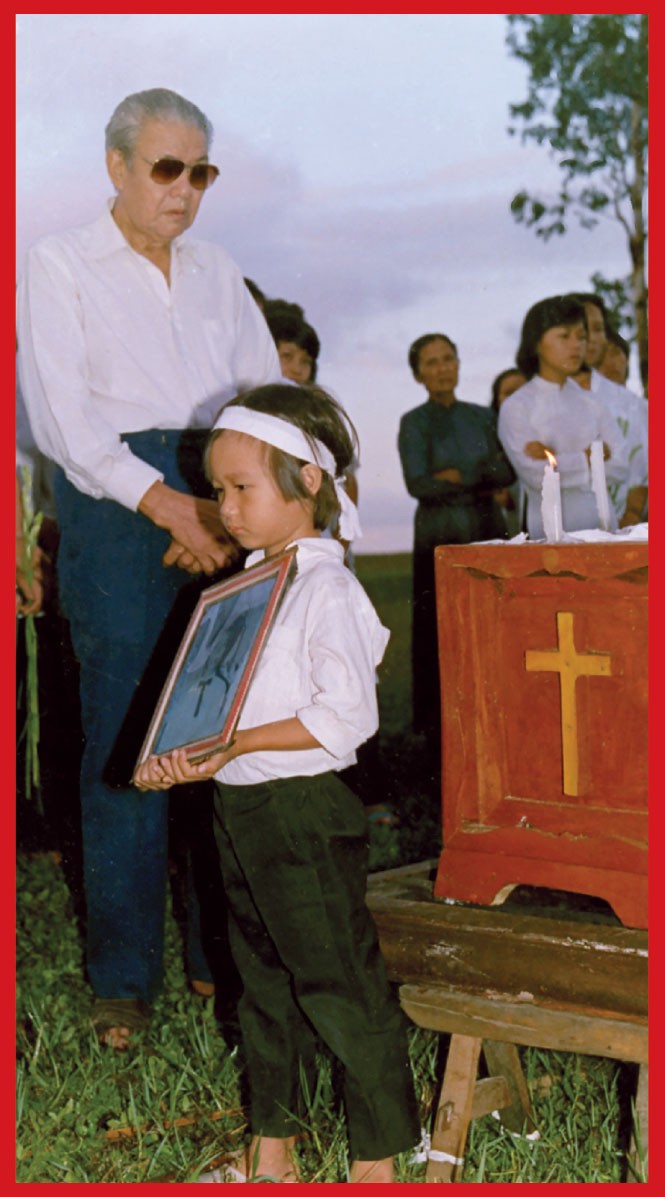

- Tam at his brother’s funeral.

Unco Fann

So, I was motivated at an early age to get proficient at English. My uncle Frank was a vital part of it. He taught me how to count and introduced me to American things like birthday gifts and helped me with difficult sounds like the "th" sound in "father." Even when I got better at English, I still affectionately called him "Uncle Frank" but maintained my original Vietnamese pronunciation that sounded like "Unco Fann." He used to thank me with the honorific ông, which meant "sir." He used to take me to Moffett Field golf course and introduce me to his buddies. He used to compliment me on my Calvin and Hobbes illustrations, even though he knew I traced them from a book. So when he died of cancer when I was in elementary school, I had not only lost a great friend but also an interpreter of American culture.

TV was also a big part of my early cultural education. I sometimes have a drawl in my speech I swear comes from Michelangelo in Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. I also watched Batman reruns from the '60s, and the part that I loved most about the show was that it featured a man who became something by adopting a persona that represented a projected ideal of himself. We also watched a lot of Family Channel shows like Big Brother Jake. We watched the nightly news, and sometimes I catch myself during class talking like an over-enunciating newscaster. You know what I mean: the voice that people of color do when they imitate white people. That voice.

So, naturally, once I picked up the English language, the thing to do was to get into the literature. I remember the moment I became aware of my language proficiency. In sixth grade, after testing out of English as a Second Language, I had an assignment where we had to write an alliteration accompanied by a drawing. Mine was: "An azure-attired Ares ate an apple on an ass." I can re-create the drawing upon request. There was a tan-colored donkey, with Ares kind of standing on its back because I didn't know how to draw him in a seated position. He had a cleft chin (of course), and was holding an apple while frowning.

I started with the Greek myths and was hooked from there. The struggle between human endeavor and fate had the ring of the Old Testament to it, and the gods' unpredictability meshed well with my Old Testament god. And so my interest in literature came from synthesizing the narratives I was accustomed to with the new traditions I saw in school.

Literature was always there at all the important moments in my life. In middle school, I got rejected pretty badly by a new girl in my English class. I told my teacher, Mr. Haughey, about it, and I remember the next day he made a photocopy of a poem about taking chances in life. He had marked it up and said it made him think of my situation. I don't remember the poem, but the feeling it gave me was what made me want to teach English. It wasn't the poem, it was the way the poem negotiated communication and empathy between two human beings. I wanted to keep being able to reproduce that feeling in my life.

- Tam and his family spent their first year in America with his Uncle Frank, second from right, and his aunt in Milpitas, Calif.

Reverse Co-opter

Having taken Post-colonial Lit, I am aware of this tension in my being so invested in Western literature. Is my consumption of the Western literary tradition just another example of servile colonial admiration for Western culture, the same way some Indians have a love for whiskey and Anthony Trollope? Or is it a sort of reverse co-opting?

Sometimes, though, I feel my knowledge of the Western literary tradition serves as a "Hey, I may not be one of you, but I sort of get you" tactic. This sort of Uncle Tom syndrome is actually something I've been accused of before. In my grad program for education, we had an exercise meant to demonstrate how learning can feel for English Language Learner students. Our instructor, knowing it was California, knew that not a lot of people would speak French; Spanish was the usual preferred second language. So, she had an exercise where she asked if anyone spoke French. I raised my hand. She gave me a French story to read out loud. I read it, and then we began to converse in French about the story. The experience did what it was supposed to do. Some students were confused, some checked out. This Vietnamese guy in the back of the room shouted, "Oh, man, you speak that oppressor language like it's your business!"

So, I carry that feeling with me, of being the servile colonial subject eager to impress. But I think I could be more generous with myself. Maybe I'm the Reverse Co-opter of Western Literature. Some of you probably had that one friend in school who was really, really into Asian stuff. Import cars. Anime. Snacks. Asian girls. The kind of guy who would try to order his ramen in Japanese, or who would get a kanji for the word "power" inked on his forearm, draped by an Asian dragon. That dude. I want to be the reverse of that dude. You got Orientalism? I got Occidentalism. I will make the Celtic cross my own. I will find Queen Victoria exotic and sexy. I want to have a misspelled Greek word tattooed onto my forearm.

If I sound like I have a chip on my shoulder, I probably do. I think that every sonnet I can write, every obscure neoclassical reference I catch, every unpacking of a poetic verse undoes one moment of linguistic inadequacy from the past. But by embracing this tradition, I further remove myself from the Vietnamese language and culture I love. Maybe it doesn't have to be that way. I live in America, after all. This is the home of have-your-cake-and-eat-it-too. The home of losing weight by eating what you want, the home of the name-it-and-claim-it gospel.

Other cultures have words for people who live in these culturally liminal spaces. Mexicans have the word pocho, for example, for Spanglish speakers or assimilated Mexicans. While I suppose I could feel some sense of shame and denigration for living in the in-between, I actually relish it. Being neither-nor helps me to be fluid, to defy and define expectations, to build myself based on my own terms. I've realized that, in order to free myself from the historical-victim trope, I should relish living in the in-between. And if this means offering narratives that challenge my present environment or prove to be uncomfortable to my audience, so be it.

So, what's the so-what? I think throughout my life I've struggled with being an in-betweener. My in-betweenness was brought out by specific policies that led to a specific political outcome that displaced me into a specific country. I've been in-between cultures and personalities; political views and priorities. And I'm sure a lot of people struggle with that, too. And, though the past may not be through with us, it is present to remind us of where we came from, and to shape our priorities about who we want to be.

I think I know now what my parents' generation's ultimate sacrifice was. It wasn't just braving the open seas to escape a totalitarian state. It wasn't just taking on menial jobs in restaurants or beauty salons to send their kids to school. In some ways, my parents and those of their generation subsumed their need to be a part of a historical narrative so that we, their kids, could have the freedom to define ourselves on our own terms.

When I think about what it means to be a first-generation immigrant, I'm reminded of what Brutus said in Julius Caesar: "There is a tide in the affairs of men, which taken at the flood, leads to fortune; omitted, all the voyage of their life is bound in shallows and in miseries. On such a full sea are we now afloat, and we must take the current when it serves or lose our ventures." We came here on a wave, for sure, but I never knew how much my parents knew they were going to be in the shallows. I suppose the only thing to do is to take the current.

Tam Hoang is an English teacher and freelance writer. This story originally appeared in the March 11, 2015, issue of the San Diego Reader.