Page 2 of 4

LIVING IN THE HOLE

Uinta 1 wasn’t always this draconian. According to several inmates’ recollections via letters, when Uinta 1 opened in the late 1980s, each of the eight sections had a television. Inmates were allowed to order from the commissary, could work for a few dollars a month, play handball and study with school self-help programs. But with each new captain transferred by the prison to run the unit, freedoms were taken away. They went from three hours out of their cell each day to one hour every other day, lost the right to work and lost access to commissary. The prison welded metal shutters onto the windows so inmates couldn’t see other inmates across the tier and welded plates to the bottom and side of the cell door.

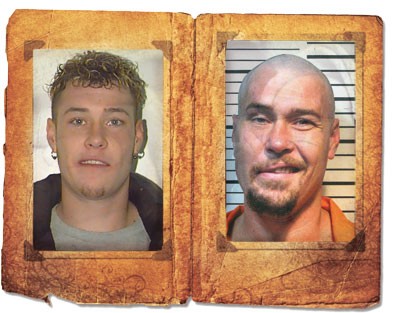

One recently released inmate who did time in Uinta 1 is Tim Redmond. Redmond was sentenced to five years in prison for tampering with a witness. He was sent to supermax for the final six weeks of his incarceration after, he says, a disputed incident during softball. “I knew it wasn’t supposed to be a nice place, and it isn’t,” Redmond says.

He was initially kept naked, he says, in a room so filthy that when he scraped his foot along the floor, it was covered in human hair. For the first three weeks, he didn’t get out of the cell except for a five-minute shower every other day. When he was transferred to another cell, every 15 minutes, day and night, a guard would open and close the slot, which squeaked, and shine a light in. “You can’t do anything. It’s like being a zoo and someone walks up to your cage.”

Redmond saw how easily it was to lose touch with reality. “I saw people going downhill each day, then I realized I was going downhill. They break people down fast in that situation. People who aren’t mentally ill become so. Your perception of reality is within that cell.”

He knew both Jeremy Haas and Ryan Allison during his six weeks in Uinta 1. “Everything is hopeless,” Redmond says. “All you can do is do your best to exist.” He never saw any of the faces of the men who were his neighbors, with whom he would shout back and forth by lying on the floor of his cell, his mouth by the tiny slit between the door and the ground. “The sad part is you never do [see their faces]. They’re just voices.”

THE ABSENCE OF LIGHT

Coleman Stonehocker has been in Uinta 1 for three months, but the 25-year-old’s understanding of solitary confinement dates back before then. He writes he has severe attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder and traits of Asperger’s syndrome, bipolar disorder and anxiety. While in a secure unit for juveniles, he was kept in a room alone with a camera. His mother, Deborah Stone, shows photographs of bruises all over her then-teenage son’s face and arms, which, he says, came from staff restraining him. He eventually hanged himself but was cut down alive. His treatment there “really put my mind where I could not trust anyone,” Stonehocker writes.

Issues with addiction and gang membership led him to burglarizing homes and pawning the proceeds for drugs. He was sentenced to 1 to 15 years for two counts of burglary, a conviction he does not dispute. In prison, he was refused his medication. “Without the meds for ADHD, people useliy don’t like me and end up trying to do me harm,” he writes.

In prison, he decided he wanted to leave gang life. That, he writes, angered a gang member, who threatened him. The prison moved him to another unit, but he was assaulted several times by gang members. He asked to be moved to another unit or prison, but instead they told him he was going to “max.” Handcuffed alone in a hallway, scared he was about to be killed, “I ended up flipping out more, they put me on suicide watch.”

In Uinta 1, Stonehocker complains, he can’t get phone calls, visits or shampoo. If he puts in a request for a mental-health visitor, he gets charged a dollar and the visit lasts only a few minutes. “I rather talk to my neighbor—he at least won’t lie to me,” he writes. His window is blocked, he gets no sunlight “and my mind goes crazy.” He writes that he is trying to move back up through the privilege levels from the low side of Uinta 1, which has the harshest lock-down restrictions, to the high side, where inmates have three hours instead of one hour out of the cell every other day and can congregate. But, he adds, “If you have one c-note, which the guards can give you for anything just because they don’t like you, you have another 30 days in that section.”

Stonehocker struggles to keep his mind healthy, he writes. It’s unfair, he argues, that having turned his back on gang life, the prison punishes him by taking away his privileges, locking him up in solitary and now he has to earn his privileges back by doing time in the hole. “It makes me not want to care about life,” he writes. “I know I do belong here for my crimes but I believe I also deserve help for my mind, this is the USA right? I have come to relize the system is just as criminal as the offenders, if not more. It’s crazy.”

A LOST CHILD

Pleasant View resident Alison Payne also wonders who “the good guys and who the bad guys are.” Four inmates have written to her, expressing their concern for her son, 29-year-old Cameron Payne.

In 2007, Cameron Payne crashed a motorcycle, which caved in the left side of his head, causing severe brain trauma. As a result, his mother says, “He’s emotionally and mentally 11 years old.” The traumatic brain injury [TBI] also took away much of Cameron’s personality, rendering him both easy to manipulate and difficult to care for. “We know we lost our son that night,” Alison Payne says. She looks down at photographs of her son trying to form a smile with his nerve-damaged features, and cries. “That’s what you get, that’s what you’re left with” after a TBI, she says.

After Cameron was convicted of aggravated assault in August 2010, Cameron’s attorney, Ron Nichols, wrote in a sentencing memorandum that “a prison recommendation will be the same as a death sentence for Cameron.” Nichols describes him as “between a third grader and an unruly teenager” in the memorandum, and noted that because the TBI had taken away his verbal filter, Cameron’s inappropriate comments “make people incredibly angry and reactionary.”

Nichols predicted that, given Payne’s “eggshell head,” he would likely be beaten to death in prison, or put in a lockdown facility.

On Oct. 22, 2010, 2nd District Court Judge Noel Hyde sentenced Cameron to 1 to 15 years and ordered that any programs or facilities at the prison that could help with his medical issues be provided.

Instead, Alison Payne says, Cameron has received no treatment since he was incarcerated almost two years ago. His prison caseworker told her that whatever the judge ordered was beside the point: “They run that place how they want to run it, he told me.” The prison decided he was normal, she says, and put him in general population.

Cameron’s parents tried to get the prison to give him his medication but say they were told it wasn’t cost-effective.

While the prison can’t comment on specific cases, it noted in its statement to City Weekly that “clinical professionals must be particularly careful about prescribing medications inside prison due to the tendency for drugs to be abused.”

It wasn’t long before Alison Payne says Cameron’s unorthodox behavior got him sent to Uinta 1.

“They’re treating him like a real person, that he’ll obey because you tell him to,” Alison Payne says. “They never give anything but deprivation. He’s gone beyond stir crazy.”