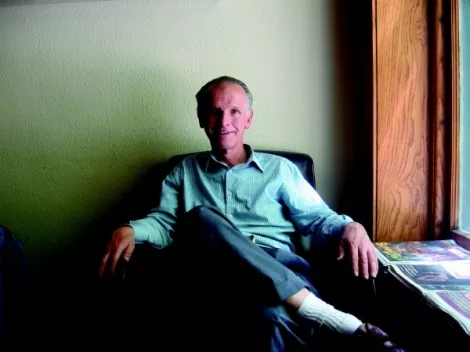

Marsh, 62, is insistent that all property belongs to God, by virtue of the Law of Consecration—an early Mormon practice of communal living—and therefore private property is a misguided concept. At St. Vincent, Marsh had been warned multiple times about annoying staff with his polite, nonstop lecturing on God’s law, until the staff eventually called the police, who cited him for criminal trespass.

Even Marsh’s attorney, Dave Rosenbloom, who is representing Marsh pro bono in his appeal of the charges in 3rd District Court, will admit that his client can talk to the point of hair-pulling frustration.

“[Marsh] hasn’t done anything but bother people with his mental condition,” Rosenbloom says. Marsh, however, says the opposite occurred, and that staff at the adjacent Road Home shelter where he was staying had threatened and harassed him. As for the charge of a mental condition, Marsh defers speculation that his persistent preaching about the Law of Consecration results from some obsessive compulsion.

“Whenever anybody hears somebody argue against something they’ve known to be true all of their life, on just a matter of faith, you’re going to appear a little crazy just naturally,” Marsh says with a laugh. No matter the legal approach Marsh and his attorney settle on, they both disagree with the court’s position of allowing a shelter to put a homeless man out on the street for simply talking too much about beliefs that shelter staff disagree with.

While the July 22, 2008, police report notes that Marsh had been warned numerous times about “harassing the employees” of St. Vincent, but to speak with Marsh is like having a discussion with a college professor about getting a term paper extended: He keeps a low and patient tone of voice, even when arguing.

He’s also not a typical homeless man, as he has access to a family trust fund that could sustain him. But he rejects it as a trapping of capitalist society.

“This is the model by which we are all strangled,” Marsh says. “When we accept the capitalist model, we actually make it so that we are exploiting the poor.”

Scott Marsh, Don’s brother, says that it’s not how Marsh says things that irritate people, but what he says. “While he’s speaking in that kind and controlled tone, he’s calling you to repentance,” Scott says. “He’s basically telling you that everyone and everything you’ve ever believed is wrong.” Scott says his brother’s preaching carries a subtle arrogance, and he won’t accept that he’s wrong. As for his intellect, Scott Marsh notes that his brother is likely only a few semesters away from receiving five different college degrees—if he wanted them.

“He’s a wonderful guy,” Scott says. “And probably the most sincere person you’ll ever find, profoundly sincere. That’s the perfect dilemma.”

Don Marsh initially represented himself in fighting the trespassing charge in 2008 at the Salt Lake City Justice Court. Taking his beliefs about equality to the court, Don challenged the charge, saying it is unjust that the state statute and city ordinance defer to a property owner’s right to cite someone for trespassing without cause.

“There is no constitutional right to a law that is unconstitutional,” Don says. He argued before Judge Virginia Ward that human rights trump property rights and that the judge had the power to use judicial review to recognize the law as unjust and dismiss the charges against him. While Ward’s February 2009 decision cited Marsh’s “competent moral argument,” she also decided “once an invitation has been revoked, there is no constitutional protection.”

Salt Lake City Prosecutor Sim Gill, while not at liberty to comment on specifics of the case to be heard July 22, did comment in general that there isn’t much leeway on the constitutionality aspect of the trespass statute.

“Morally, it may not be fair to push me out on the street,” Gill says of a situation like Don Marsh’s. “But legally, they have that right.” Gill also points out that the venue is important to consider, since a shelter can serve a private/public function, and that if someone is being a nuisance at a public library, for example, then “in essence they have changed the use of that public space for the rest of the folks there; at that point [staff] can ask you to remove yourself.”

That argument is echoed by Jose Lozaro, director of St. Vincent. “If someone is causing a problem and threatening staff, we need to have the ability to ask someone to leave,” he says.

Don Marsh appealed the ruling to 3rd District Court, where Rosenbloom stepped in to represent him. While Rosenbloom and Don Marsh may be approaching the case from different angles, both are concerned that the rights of an indigent man were quickly squashed by a knee-jerk acceptance of the pre-eminence of property rights. Rosenbloom says that since his client was invited to the facility, the shelter needs a better reason to call the cops than Don Marsh being annoying, especially if Don’s behavior is a mental condition. If his client’s offensive behavior were physically manifested, he says law enforcement wouldn’t recognize it as grounds for nuisance.

“It begs the question as to what extent can a director of a homeless shelter send someone into the streets,” Rosenbloom says. “If he’s a health hazard? Sure, I guess, but what if they snore? What if they mumble under their breath? How they bother somebody else can be purely discretionary.”

While no mental-health assessment has been done on Don Marsh, Rosenbloom is confident he can establish his client’s obsession for social equality through the testimony of friends and family. Rosenbloom hopes to challenge the court and Judge Terry Christiansen to recognize that the law needs to carefully scrutinize whether or not a soft-spoken, albeit long-winded, 62-year-old man can be considered a nuisance by a staff which deals with homeless people every day. And more importantly, he wonders why the staff couldn’t ignore what he had to say if they disagreed with it.

Don Marsh, however, hopes the court can recognize that it does have the ability to do what’s right, even if it’s not technically legal.

“The court isn’t there to hear that, they’re here to hear the fact that you were told to get off the property and you didn’t,” Marsh says. He cites LDS scriptures from the Book of Isaiah that argue the law should not be used as a tool against the disadvantaged. “Do not allow people to take the helpless, the poor, the widowed and the fatherless before the court and be convicted for things that have no proportion to reality.”

|

Eric

S. Peterson:

|