On June 1, 2007, at 8 a.m., Michael Birkeland blearily opened his eyes to a clear blue sky. He was lying naked in a field in Orem, his clothes scattered around him, his car a few yards away, the engine still running.

Birkeland had been at a party until 4 a.m., riding high on cocaine. He had no idea what had transpired in the missing four hours. As he picked up his clothes, he realized it was his young son’s birthday.

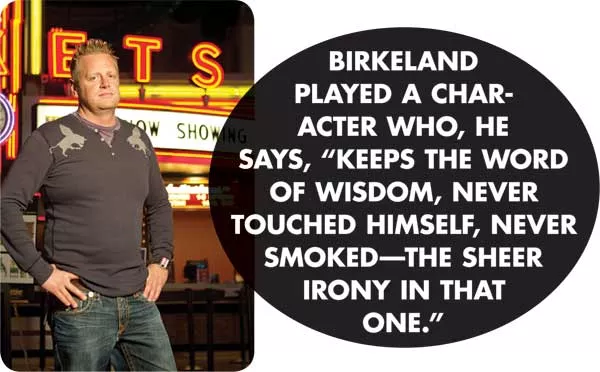

Such a descent into a narcotics-drenched oblivion has its roots in events five years before, when the stand-up comedian and actor was at the center of a nascent LDS-comedy-film boom, playing in a supporting role an earnest “Peter Priesthood” church member in the first Mormon comedy, The Singles Ward.

The low-budget independent film, aimed at Mormons and made by Mormons, launched the careers of actors Kirby Heyborne, Will Swenson and Birkeland, among others. It told the story of a divorced, lapsed Mormon who found success as a stand-up comedian, only to be drawn back to ward life by his attraction to a singles ward’s activity director. While Heyborne and Swenson parlayed that initial success into mainstream careers, Birkeland’s fame was limited to Utah and international Mormon communities through a series of roles in LDS-comedy movies made in the mid-2000s.

Born to devout Mormon parents in Tennessee, his rise and subsequent decline has all the ingredients of a Utah County spin on a typical Hollywood tale. “I let the social side [of success] take over, I let it ruin my life,” says the 40-year-old. His tale also echoes the boom and bust of the LDS comedy films that made him a local star. He argues those involved in the films’ production were “cursed a little bit,” even offended God. “There was too much pride. It got to all our heads.”

Friend Brandi Daniels has known Birkeland for years. She feels Birkeland wants the best of both worlds. “He wanted the quintessential Mormon family life, the wife, the children. But he also wanted the fame and the fortune that comes along with it. I don’t think you can do both very successfully.” Indeed, being Mormon in the entertainment business comes with its unique stresses. Mormons, she says, “want somebody to stick to their values and standards. If I see an LDS actor, I want him to have LDS morals; I don’t want to hear he’s been drinking and partying.”

In a world that’s full of people named Michael, Birkeland says, “There’s only one Michael B, baby,” jerking his upright thumbs at himself. Michael B is the nickname given to him by a friend introducing his stand-up act. His friends call him that or simply “B.” But trying to tell “B’s” story isn’t easy. For a man constantly texting, he can cease communicating for days on end at the drop of a hat, then resurface as if nothing’s happened, leaving some frustrated friends to ponder what they see as a lack of stability. Even the idea of a story on Birkeland makes some of his friends scratch their heads. “You just never know quite what to believe, but it’s always entertaining,” says stand-up comic Dave Nibley, with a laugh.

Birkeland has so many wild, tough-to-verify stories that sorting out truth from drama, whether his or others, isn’t easy. “I’m a comedian,” Birkeland says. “Of course I embellish.”

So, ladies and gentlemen, this is Michael B’s story: truth, legend and everything in between.

Birkeland’s saga threads through small roles in The Singles Ward, a film that eerily sketches out some of Birkeland’s later life, and The R.M., to a starring role in the LDS comedy Home Teachers, followed by a two-year stint managing a Provo comedy club. But behind the scenes, his appetite for drugs, drinking and partying led not only to his divorce but, finally, in an Orem field, to a confrontation with what he calls his “carnal appetites.”

“I took all that God gave me and threw it out the window like a freaking bitch,” he says. “I became this proud person full of shit, all this knowledge I was doing nothing with.”

After his cocaine-driven wake-up call, rather than a 12-step program or counseling, Birkeland says he locked himself away in a hotel room for 10 days and quit cold turkey. “I was bleeding out of every hole in my body,” he says.

Such drug usage stands in sharp contrast to his love of studying the Book of Mormon, earning him a reputation among his friends as a “scriptorian.” He says he became a man obsessed only with learning about faith, not following. That passion for Mormon doctrine did not prevent his 2003 excommunication from the LDS Church. “I willingly broke the commandments. I did it so many times I didn’t have any feelings.”

But three months after his 2007 drug-binge black-out, Birkeland hiked up the side of Mount Timpanogos. He had lost “everything spiritual in my life.” He stood on the edge of a cliff, by a small fir, the white waters of a raging river several hundred feet below. “I wasn’t trying to kill myself. I am the least suicidal person you’ll ever meet.” Rather, he says, he wanted answers. He needed to know he mattered, that there was something more to him than just being Michael B.

“That’s me on that freaking mountain, by myself. Do I matter?” he asked God. Then he closed his eyes, lifted his arms from his sides and leaned forward into the thin air.

Freeze frame that moment of the then 36-year-old blond, spiky-haired man, frozen on the lip of doom, and you see someone caught between mammoth contradictions. A man who yearned for fame, yet loathed the emotional isolation it brought him. A man who daily broke the rules of his faith, yet misses nothing with more passion, besides his children, than the divine guidance his church took away from him with his excommunication.

Birkeland was “angry at the whole world. I knew one day I’d start repenting. I would feel guilt and sorrow. I put it off and put it off until it destroyed my life and marriage. And then I woke up naked in a field and never looked back.”

CHOKING FOR JESUS

Birkeland’s parents are devout members of the LDS Church and have gone on five missions. “It’s their life,” he says. They raised him, their four other boys and a daughter in Chattanooga, Tenn., hostile territory for Mormons, Birkeland recalls.

Davy Kammer grew up with him. “He was frigging funny, dude, unbelievably hilarious, always the center of attention.” Another friend, Tim Treadway, recalls laughing so hard in church at his jokes he’d have to leave. “Now, he has a lot of complications in his life, so he doesn’t make me laugh so hard.”

Birkeland says when vandals broke into the single-wide trailer that housed the LDS seminary, they smeared feces over the walls and scriptures. He and his brothers tracked down the culprits. Birkeland cornered one in the gym. “I put him in a chokehold and told him the importance of leaving members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints alone.”

Beyond the schoolyard slapstick and the struggles of being Mormon in a Baptist-dominated state, what Birkeland shared with very few was that he was systematically abused from ages 7 to 14 by two middle-age women music teachers his parents sent him to for lessons. As an adult, he took anger-management classes, he adds, after violently confronting the abusers at their Chattanooga home.

But to his friends, he was the life of the party. They expected him to be a star. “We thought he’d be on Saturday Night Live or making movies in California,” Kammer says.

FAT WHITE DUDE

Birkeland went on his LDS mission to Sacramento, Calif.—home, he notes wryly, to the “headquarters for Ex-Mormons for Jesus. All I could think was, ‘Am I ever going to get away from the antis?’ ”

Birkeland met his wife, Melissa, at Ricks College (now BYU-Idaho) in Rexburg, Idaho, in 1993. They were married months later and moved to Utah County, where they had four children. Melissa, now remarried and relocated to Idaho with Birkeland’s children, declined to comment for this story.

In the mid-1990s, Birkeland says, he began to use drugs. He started with speed as a cheap alternative to his attention-deficit-disorder medication, then added cocaine and marijuana to the mix, the latter to help him sleep. He bought his drugs from a friend out of state and was “very secretive” about his usage. He didn’t lie to his bishop about his pursuit of illegal highs, he says, “I just didn’t bring it up.”

Birkeland friend and stand-up comedian Dave Nibley characterizes the Southern-born actor as “almost like the genie from Aladdin, Robin Williams on speed.” He speculates that Birkeland’s exhausting ability to be “on” all the time may have eventually driven him “to the dark side.”

To some in his LDS ward, like his friend Brandi Daniels, his life seemed perfect. “I’ve never seen anyone exude that energy.” She admired him as a husband and father. “I always wondered how they did it, how they kept it all together.”

In the late 1990s, Birkeland realized the road to success lay with putting on weight. “When you’re white, you’re just another white guy,” he says. “But a John Belushi, a Chris Farley, the fat white dude in the 1990s, it worked. It’s what gives you the edge on somebody [in an audition]. I started booking commercials. The second I lost weight, I stopped getting booked.”

NAIL IN THE COFFIN

In 2000, Birkeland was introduced to aspiring filmmakers Kurt Hale and Dave Hunter, who had set up a production company, Halestorm Entertainment. With the success of God’s Army, director Richard Dutcher’s pared-down tale of LDS missionary life, Hale and Hunter realized there was a potential goldmine in Mormon cinema. No one had ever done a Mormon comedy, and when writer John Moyer offered them his script about romance in a singles ward, they jumped at it.

“Within Mormon culture, it’s a no-brainer to do a comedy on a singles ward,” says actor-turned-director Daryn Tufts. Singles wards are for unmarried and divorced members of the LDS Church, providing ecclesiastically sanctioned opportunities for dating along with religious teachings.

Birkeland played a character who, he says, “keeps the word of wisdom, never touched himself, never smoked—the sheer irony in that one.”

Actor Kirby Heyborne marveled at Birkeland’s ability to run into doors or fall off tables without getting hurt. “He’d make these crazy faces and you would die laughing.”

Like Heyborne, Tufts had a supporting role and recalls Birkeland as akin to “the Tasmanian Devil in Looney Tunes.” Birkeland, he continues, “is like a twirling gravity that sucks everything to him when he walks into a room.”

Some were unhappy with the finished film. Dutcher, who did a cameo for The Singles Ward, walked out of a final-cut screening “knowing in my heart it was the first nail in the coffin of Mormon cinema.” Instead of quality films coming out of Halestorm, he saw “frat boys finding ways to finance their parties.”

Hale says he told Dutcher, “There’s room for both of us.” Tufts also had mixed feelings. “It had a lot of heart, likeable characters, but the jokes were far too amateurish, picking low-hanging fruit.”

NAKED COWGIRL

With the finished print in the bag, Birkeland, Heyborne and several of the Halestorm team toured the Southwest in a car with the Singles Ward logo wrapped around it. They would stop at ward houses to talk about the film to young members prior to a screening.

The first weekend of its release in Utah, “the movie didn’t do shit,” Birkeland says. The local reviews were disparaging, but after a singles group from BYU saw the film, “it skyrocketed. We were LDS icons overnight.”

Friend Angie Larsen, former host of KTVX’s Good Things Utah, had Birkeland as a guest on her show. “The audience would go nuts, a standing ovation,” she recalls. “He was a hit, especially with the ladies. Women are drawn to people who make them laugh.” Stand-up comic Nibley says Birkeland had “girls all over him all the time. In a kind of Hollywood sense, he milked that celebrity, took advantage of it.”

But the success of The Singles Ward and then The R.M. brought him, and others involved in the films, unwanted attention in the form of ardent female—and occasionally male—fans.

A woman naked but for cowboy boots and hat turned up on his doorstep. Another woman, he says, crawled through his son’s bedroom window.

His friend Nate Keller sees part of the problem stemming from Birkeland “being as open and friendly as he is. He’s probably disappointed people over the years who think they know something about him and don’t.”

EXED

In 2003, Birkeland’s lifestyle and his faith collided. He says he went to his ward to talk to the bishop about his problems fulfilling the church’s dictates on lifestyles issues, only to be confronted by a pregnant woman who claimed he was the father and local church authorities who believed her. Despite his angry and sarcastic denials, the local church authorities did not change their minds.

A few weeks later, he found a letter by his front door that stated he was no longer a member of the church. His excommunication, he says, hurt his father. “I think he could feel my deterioration. He didn’t raise me to be that way.” But he adds, “I chose to be that way. I know exactly what I’ve done is wrong. I just didn’t care enough to feel guilt or change. So I made it worse.”

By the time he starred in Home Teachers, Birkeland was so “jacked up on drugs” he can’t remember shooting some of the film’s scenes.

Home Teachers referenced the LDS practice of male members making monthly visits to assigned families in the ward. What producer Dave Hunter told a reporter were “homages” to Tommy Boy and Planes, Trains and Automobiles, the Deseret News’ movie critic Jeff Vice termed as “verging on comedic plagiarism.”

But Hunter ranks Home Teachers as his personal favorite of the LDS films he produced. “It was a funny buddy road comedy,” he says, but because Mormons hate home teaching, “it was a failure, it didn’t recoup its money. It’s the film people hate; I still get hate mail about it.”

PRIDE BEFORE THE FALL

In 2005, as the trajectory of Mormon cinema waned, Birkeland opened Provo comedy club Fat, Dumb & Happy with a friend. It initially brought out-of-state comedic talent to Utah, with the proviso that the comics used only clean language. It closed after two years.

Birkeland got divorced in 2006. Already partying hard, he threw himself further into drugs, alcohol and women. Several of his friends say he was also dealing drugs, but Birkeland declined to comment on their stories.

He makes a parallel between his decline and Halestorm’s. “I think we were all punished by the Heavenly Father,” he says. “Too much pride. We all thought we were better than others, and that gift [of success] was taken away from us.”

Director Hale disagrees. “To put that burden on God is unfair,” he says dryly. “You create your own success and your own demise.”

Nevertheless, Halestorm’s bid to go mainstream with the 2006 Church Ball saw the Mormon comedy movie genre stumble its final steps. According to The Salt Lake Tribune, a lawsuit claimed the film’s budget had climbed to $1.2 million without the approval of investor Bryan Lampropoulos. Lampropoulos sued the production company for $6 million in late 2007, but the 36-year-old died suddenly in March 2008. Halestorm counter-sued, alleging Lampropoulos’ company had failed to properly finance the film’s making.

After riding the Mormon-cinema boom for seven years, Hale is the first to admit “we may have worn out our welcome,” producing and distributing so many films so quickly, that by 2005 the audience began dropping off.

Birkeland, meanwhile, was dealing with his own problems. After waking up naked in a field, he knew he had to change his life. He told his father over the phone, “I’ve gone too far.”

Hale says Birkeland disappeared for eight months after the field incident. “Whether out of personal shame, that he let down his close friends, or whether he hit bottom and was digging at that point, he went off the map.”

Friend Nate Keller points out Birkeland has never lost his faith. Even when he was deep into partying and drugs, Birkeland never said such a lifestyle was the right thing to do, Keller says. “He’s really looking for a real deep jolt that can just help him to become back as he was.”

Birkeland says he found that “jolt” leaning over the edge of a Mount Timpanogos cliff face. Something extraordinary happened, he says. “This unbelievable wind, this pressure,” blew him back. “I went slam, backward, down on the ground.” He lay there, stunned, even as memories played out before him.

He was 6, lying on a dock by a lake in Tennessee, “the trees and the grass greener than all, the water clear, the sun perfect. It’s my first memory of peace.”

Then he was on his mission, being told by the spirit that possessed a woman he was exorcising, “If you do not stand firm, we’ll have you.” That was replaced by a Scottish elder at the LDS missionary school reducing Birkeland and other young missionaries to tears with his passionate teaching. Birkeland witnessed again the birth of his children, and with it, “the most peaceful feeling.”

GO WEST YOUNG MAN

As Birkeland climbed down the mountainside, he wanted a new life. He moved to Sandy, changed his e-mail, temporarily closed his Facebook page and changed his phone number—the latter a not-

uncommon occurrence, say friends. “I went off the grid,” he says.

But even after disconnecting himself from the world, his trials continued.

In 2008, Birkeland was charged with theft for allegedly stealing a professor’s laptop. Angie Larsen was anchoring Channel 4 news when she did the story on her friend’s arrest. “It was shocking. It was hard for me to get the words out.”

After years of breaking the law, Birkeland admits, he went to court for a crime he insists he did not commit. He nevertheless pleaded no-contest and was sentenced to 12 days of work diversion and put on probation. “It’s one of the best things that happened,” he says now. “I didn’t get away with something I didn’t do.”

Along with producing and hosting local TV shows, Birkeland also went into mortgage refinancing with a friend of 17 years. But after two years, that business relationship ended abruptly, along with a stormy four-year personal relationship with a Brazilian fashion store owner. Despite these setbacks, he remains upbeat about the future, focusing in part on his own life story. He intends to make a documentary—What Makes Me B—about his journey back to his church. Very few of those excommunicated, he says, return to the church. “They feel like there’s no hope, that they will be judged for the rest of their lives.”

Dutcher argues Birkeland’s comedic talents “are for a bigger audience, better movies. His time is better spent, and his talent better appreciated, elsewhere.” That’s a route that Birkeland’s fellow Singles Ward stars Swenson and Heyborne have profitably taken. Will Swenson was nominated for a Tony Award for his performance in a Broadway production of Hair, while now-Los Angeles-based Kirby Heyborne, despite criticism in Utah of his appearance in a Miller Lite commercial, was picked by directors The Farrelly Brothers (There’s Something About Mary, Dumb & Dumber) to act in their upcoming comedy The Three Stooges.

NO MORE MICHAEL B?

The main prize for Birkeland—at least for now—is returning to the LDS Church. “Got to get that Holy Ghost back, man,” he says. “But coming back, it’s the hardest thing.”

He met with a church authority, who instructed him to make a list of 10 things to give up and 10 things to take up. He chose to give up coffee and take up praying.

While Birkeland wants to bear his testimony at the Midvale singles ward he attends, his excommunication forbids him from bearing his testimony and taking the sacrament. Twice, church authorities have told him he is not ready to be re-baptized. But in early December, however, he writes in an e-mail that the LDS Church has decided he can be re-baptized. “April 2012, baby. I’m back.”

But some of his friends wonder how deep the change has really been. Tim Treadway has been friends with him for 22 years. “I care about him,” he says. But he worries Birkeland is running out of options. While “deep down he wants to get to a better place, he doesn’t have any idea how to get there.” Treadway fears Birkeland may not “have the humility to accept what it’s going to take to truly get there. I think he’s still lost.”

Angie Larsen disagrees. She characterizes Birkeland as an “unstoppable force. He has been kicked down, beaten and broken, much of it his own doing. But he has this undeniable strength, this spirit, and he continues to fight back. His goal in life is to help people laugh, find humor and joy. I think that’s his life’s calling.”

However, as with so many famous comedians with dark sides, Birkeland finds his own funny-man persona irksome. He says, “I became the court jester” to friends who were interested only in him making them laugh, not in hearing about his ongoing struggles. “No more Michael B, no more funny, crazy guy,” he says. He is tired of “everyone putting quarters in this monkey,” he says, violently clapping. “Everyone wants me to be the funny guy. What do I want?”

His American dream, he says, “is to entertain people, then go home to a life that I find beautiful, to a wife and children.”

Despite the ups and downs, the angst and the anger, he says he is at peace. “I am a good man,” he says, paraphrasing advice from his father. “Now it’s time to become a great man.”