“I used to walk around and feel like I was still in Africa,” he says. “I’d see so many Sudanese, Somali Bantu, it felt good … but now you don’t see a lot of them.” While Hartland apartments used to be an oasis of diversity where refugee families found safe haven, new ownership priced out more than 80 families last summer and, even as community leaders have set up an emergency fund to help the remaining families, the apartment owners won’t accept their money. By year’s end, 30 more refugee families will be evicted.

Landlords are finding that while subsidies could keep low-income housing profitable, the bigger buck is in luxury condos. If maximizing the bottom line means displacing the already displaced, then the market has spoken. Some just don’t like what it’s saying.

“Over half the population that was here in August is gone now and, this fall, we’re still seeing more notices of nonrenewals, says Kimberly Schmit, coordinator of the University Neighborhood Partners Hartland Center. “Over 80 percent of the families we work with here have said they’ve been asked to leave by management.”

In a 300-unit complex at 1700 South and Redwood Road, the Hartland Center keeps the old name of the apartments while new ownership has christened the site “Seasons at Pebble Creek.”

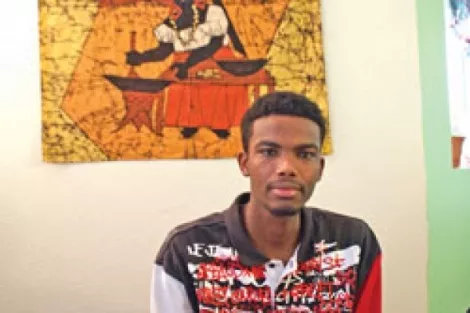

“I wonder where the creek is,” Abde quips as he walks the grounds of Hartland. Abde is also a coordinator at the Hartland Center and proudly shows off the resources the center offers: a preschool, ESL program and after-school services are all provided in converted apartments. Even the main office is a converted two-bedroom apartment with a computer set incongruously next to the kitchen sink.

Despite the forced diaspora, families are still traveling back to the Hartland Center to receive support. “We’re just as busy as before. Those who have moved out are coming back to access our resources,” Schmit says. “[But] our concern is with the dislocation of the families that built the center. They’ve moved all over and they lose that strength and network they once had.”

The complex is changing quickly. While young African children play on the playgrounds, their laughter is all but drowned out by the construction; crews are working fast to finish the conversion to condos before winter when the new owners are due to move in.

Abde is aware of the change and for being as close to the controversy as he is, soberly understands why refugees are being forced out. “It is business. They [the new owners] wanted to make more money. People here don’t have a lot of money.”

But that’s not to say money isn’t available. Indeed, emergency funds were set up by the Salt Lake Community Action Program (SLCAP). Schmit says enough money exists to help tenants pay the rent increases, if they were even given the chance.

Officials with Seasons at Pebble Creek did not return calls to City Weekly seeking comment. But management last summer had argued that previous ownership offset losses with subsidy money—an option the new owners didn’t have. Norman Nakamura, state coordinator for refugee resettlement in Utah, disagrees.

“There’s plenty of subsidies available,” says Nakamura. “It’s just more lucrative for landowners right now to get out of low-income housing.” The housing shortage has made properties so hot that many landlords perceive a better investment to be in converting low-income housing to condominiums. And, while the wheels of the market seem to run right over many of Utah’s most disadvantaged tenants, the fine line between housing market catering and discrimination seems blurred, especially with refugees.

“The problem is landlords have one bad experience with refugees and then say, ‘Oh, I won’t rent to this population again,’” says Sharon Abegglen, housing director for SLCAP.

Abegglen says refugees often struggle to adjust to the basics of American living. “They sometimes don’t know about refrigerating food, and there are issues with bugs, or large families in one apartment.”

She recently met with the newly formed Housing for Refugees Committee including Catholic Community Services, LDS humanitarian aid leaders and many others working on how to find housing for Utah’s most vulnerable. This committee plans to acquire or build new facilities specifically for refugee and low-income housing, and also to expand services to ease refugees’ transition, ideally for their first two years. The plan includes a voucher program, as well.

While vouchers may be a loaded term lately, these would be more like short-term assistance. Most low-income tenants try to take advantage of Section 8 subsidies, which help out in the long term, but Abegglen says, “There’s about a two-year wait to get Section 8 assistance. This would be short-term assistance they could use for maybe two months. Then if something happens, maybe somebody gets sick in the family, they can get back on the subsidy if they need to.”

The needs-based vouchers would be issued on a case-by-case basis and would help families in the most vulnerable periods of their integration into the community, she says.

While activists wait to acquire property, the looming concern is whether or not landlords, in the meantime, will even accept these emergency monies. But Hartland coordinator Schmit is confident the refugee community will make it in the tough interim. “These people aren’t just victims. They’re a community of survivors.”