Page 2 of 3

Gollaherville

Scott Gollaher grew up in Cottonwood Heights on a street lined with modest ramblers. The youngest of four brothers with a younger sister in tow, according to 1996 testimony by Gollaher's defense attorney at his sentencing, he left home when he was 14 and, two years later, opened his own concrete-contracting firm—even employing two of his own high school teachers during the summer.

In the late 1970s, he went on a LDS mission to Alberta, Canada. Gollaher married and had two children (he and his first wife divorced in 1998). He grew his company, employing 45 people, including ex-felons, homeless people and those down on their luck, according to court documents. He developed residential properties, notably several apartment complexes in Holladay, which residents nicknamed "Gollaherville."

Gollaher routinely set himself at the center of his Holladay, Utah LDS ward's social life, according to neighbors and former friends, by a combination of overly familiar bluster, pushiness and acts of kindness, such as ploughing people's driveways clear of snow.

In the early 1990s, Gollaher's friend and fellow ward member Alan Call and his wife Liz were struggling with their marriage. "That made us vulnerable to Scott's helpfulness," Alan's now-former wife Liz tells City Weekly. Alan Call and Gollaher went on camping trips together, where the latter solicited information about the marital strife, Alan recalls.

That friendship came to a deeply bitter end when the Calls' daughter Sarah said Gollaher had taken advantage of the family's trust to molest her, allegations that ultimately led to a jury sending him to prison.

Gollaher had hired Sarah Call to do ironing and to babysit his toddler son. In 1994, after watching a 20/20 special on child-sex abuse, Sarah, then 11, told her mother Gollaher had touched her genitals the year before while she slept on an outdoor trampoline at Gollaher's house.

- Gollaher (left) with Morgan County prosecutor Jann Farris

Attorney Helen Redd grew up with Gollaher's younger sister. When news broke in the ward about allegations of child sexual abuse against Gollaher, his ward members initially defended him. "The instinct was to rally around him," Redd says. In the process, the Calls were shunned.

"The fall-out from him being arrested was we were completely ostracized," Liz Call says. "People would talk about the things Scott had done at Christmas time, the clothes he had given away, the help he had given people looking for work," she says. "He was practically a saint."

Redd, along with many others, wrote letters of support for Gollaher after the jury reached a guilty verdict.

Gollaher fought the conviction, fired his attorney and filed motions seeking to undermine Sarah Call's testimony. But on Aug. 15, 1996, Judge Timothy Hansen sentenced him to one to 15 years in prison, telling Gollaher that what Sarah testified in court, "is the truth. Whether you accept it, whether you're willing to accept it, whether you know it or whether you don't, that's the truth."

Shortly after, he was excommunicated from the LDS Church following a church court in Holladay, an event that distresses him to this day. He's concerned that publicity about his excommunication could hurt his defense in his upcoming trial in Mormon-dominated Morgan County.

A Knock at the Door

Gollaher maintained his claims of innocence throughout much of his time in prison. "I have no conscious memory of touching her," he told a parole-hearing officer in a November 1998 hearing about the night on the trampoline.

Back then, some in Gollaher's family still believed him. One of his nieces told a friend that her uncle "wasn't in jail for hurting kids. He's on a mission. The Lord sent him to help other people."

But some of those who had believed and supported Gollaher throughout his prosecution were in for a horrific surprise two years after his conviction. In early 1998, according to a Salt Lake County Sheriff's police report, Gollaher's first wife gave the police lists of names that were written by her husband while in the Salt Lake County jail.

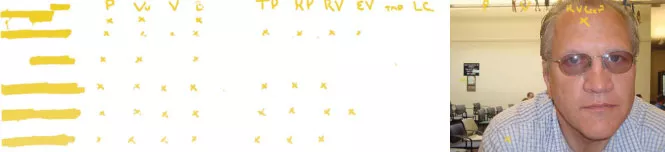

The four pages Gollaher had compiled included names of more than 100 pre-teen girls, who had, during his teenage and adult years, lived in the south end of the valley. A series of 10 separate initials ran along the top edge of the paper, x's marked against the names below some or all of the initials. Uniquely among all the names on the list, the line containing Sarah Call's name ends with the word "guilt."

Then-Salt Lake County Sheriff Det. Mike Mitchell theorized, according to notes City Weekly gained through a record request, that the initials were potentially references to acts of abuse: 'TP,' touch penis, 'RV,' rub vagina—constituting what Mitchell thought was a possible victim log prepared by a convicted pedophile.

Gollaher told a parole-board hearing officer that he wrote the list for himself, "simply to list as many young girls" with whom he had been alone, in case he needed to defend himself against future false accusations of abuse. Gollaher alleges that an attorney working for his first wife had used the four-page document—which he claims was altered from what he wrote—to undermine his support, as some of those who had sided with him against the Calls' accusations found their own children's names on his list.

When a detective knocked at Redd's door and showed her Gollaher's list with her daughter's name on it, her ears rang as if she were in a tunnel. "Why didn't I realize this was going to happen? Why didn't I have her checked?" she thought. Redd repeatedly asked her daughter but she did not remember any abuse.

Bottom line, Gollaher says, while in jail looking at the reporter through the glass, the "list" investigation did not result in a single charge, despite exhaustive efforts by detectives to interview parents and their children. "How does that feel going up your ass?" he asks.

The parole-board hearing officer said at the 1998 hearing that the letter that had most impacted him regarding Gollaher was one from the inmate's sister urging the board to keep her brother locked-up until he could tell his victims he was sorry.

Apologizing, however, was something Gollaher struggled to do. It had cost him so much to deny his guilt for the crime he had gone to prison for, he told the hearing. "Can I admit to Sarah Call? I've spent $133,000 saying I haven't. I'm divorced; I'm in the process of having my parental rights terminated, in the process of losing roughly $1 million," he said. He then said he would admit to molesting Sarah, "if it could make anything better. These people seem to be pleading for my acknowledgment that I have a problem."

In order to parole, Gollaher had to admit to a crime. "I was on a 1-to-15," he says now. "Absent the admission of guilt, they're going to give you silent time. It doesn't matter how innocent you are, you're going to do the time." He says, "It took me a very long time to say to the board 'I accept responsibility.'"

In 2000, he was released to a halfway house.

Friends No More

Post-prison, Gollaher shifted his business model from residential to commercial development, putting up an office complex called Trackside on the west side of Salt Lake City, then turning an adjacent warehouse into a marble and granite entertainment venue called the Rail Event Center.

Among those Gollaher involved in the Rail was his then-attorney Blake Nakamura—now one of two deputies over the Salt Lake County District Attorney's criminal division—and one-time LDS mission companion turned contractor, Scott Cook, a former friend going back 30 years. As a convicted felon, Gollaher couldn't own a liquor license. According to district-court documents, Gollaher's second wife, Sharon, whom he married in 2004, leased the property, which was in her name, to Nakamura and Cook, and they were to run the venue.

Gollaher's penchant for helping others, including single mothers and their children, repeatedly got him into trouble. His parole was revoked four times, the last time stemming from an encounter on Christmas Eve 2009, when he went to a Walmart to meet a former tenant to buy presents for her children. An anonymous call to his parole officer alleging he was with not only the mother, but also her children, resulted in him spending nearly five months in prison before the parole board decided to terminate his parole a year early on June 8, 2010, in part because of a recommendation by Adult Probation & Parole.

It was only a few months later that Gollaher was again the subject of law-enforcement interest. On Oct. 25, 2010, he visited a single mother's home at 9 p.m. with sunflower seeds, cookies and ice cream for the woman and her children. A young Hispanic girl present at the gathering alleged Gollaher touched her "private spot" while she sat on his lap surrounded by numerous children and teenagers. The child's mother phoned the Salt Lake City Police Department who brought in Gollaher for questioning.

"I'm sensing a pattern here, Scott," an investigating SLCPD detective told him in a transcribed interview, referring to his prior conviction and the Christmas Eve 2009 allegation.

"That I help people out?" Gollaher replied. Then he added, "Somebody could call that grooming, couldn't they?"

On Nov. 3, 2010, Sim Gill was elected to Salt Lake County District Attorney and appointed Blake Nakamura as deputy chief of his criminal prosecution division. By then, the Gollahers had filed for bankruptcy and, after 2011, had no further links to the Rail. The relationship between Gollaher and Nakamura and Cook had deteriorated to the point that wife Sharon Gollaher sued to evict Nakamura and the Rail Management Group.

In the midst of his losing battle for control of the Rail, Gollaher was charged by the Salt Lake County District Attorney on Nov. 12, 2010, with a single count of child sex abuse.

Sim Gill's office issued an internal memo in February 2011 to identify Nakamura's potential conflicts of interest, including Gollaher's child sex-abuse charge. But it wasn't until June 6, 2011, that Gollaher's case was handed over to the Utah County prosecutor's office. Two and a half months later, Utah County prosecutor Craig Johnson dismissed the charge after the victim's aunt recorded a 10-minute conversation with the victim where the child recanted her claim. Gollaher provided a copy of the audio to City Weekly, claiming that former business associates had attempted to set him up. The little girl told her aunt that her mother's best friend had promised her a "bike or a scooter," if she lied about Gollaher molesting her.