In Utah, there is a limitless air to many things, including child birth rates, energy development, love of corporate chain stores and the Legislature's dislike of the Obama Administration.

Utah is also one of 12 states that allows individuals, and one of only six states that permits corporations, to contribute unlimited sums of money to candidates seeking public office—a distinction that, if the common refrain that money is a corrupting influence in politics is anywhere near true, makes the Beehive State an unkept wound begging for infection.

"It's about as minimally regulated as can possibly be," says Matthew Burbank, an associate professor of political science at the University of Utah, on the state's campaign finance laws. "There are a couple of other states like us, but most other states, in general, have adopted the kind of notion that big contributions are the source of the problem, and so that's what we want to stop."

The manner in which candidates bankroll their political dreams has emerged as a key issue in the Republican gubernatorial race, which is pitting incumbent Gov. Gary Herbert against Overstock.com chairman of the board Jonathan Johnson. Both candidates have accused the other of kowtowing to political donors, but in very different ways.

In the case of Herbert, who in April was recorded telling a group of lobbyists that he would happily meet with their clients in exchange for large campaign contributions, the accusations from the Johnson camp have centered on the governor's seeming willingness to grant face-to-face time to top donors. Johnson's campaign manager, Dave Hansen, told The Salt Lake Tribune that the governor's efforts are a "pay-to-play program. Other officials characterized Herbert's behavior as "speed dating."

As Herbert grappled with the fallout from this scandal, which even some lobbyists being courted by the governor said made them "cringe," Johnson has accepted five campaign checks from his boss, Overstock.com founder Patrick Byrne, for a combined $650,000.

The Herbert campaign has been quick to insinuate that Byrne's well-endowed campaign contributions are an effort to buy the governor's office, and that voters should look closely at what the wealthy man hopes to gain by almost single-handedly financing his employee's political aspirations.

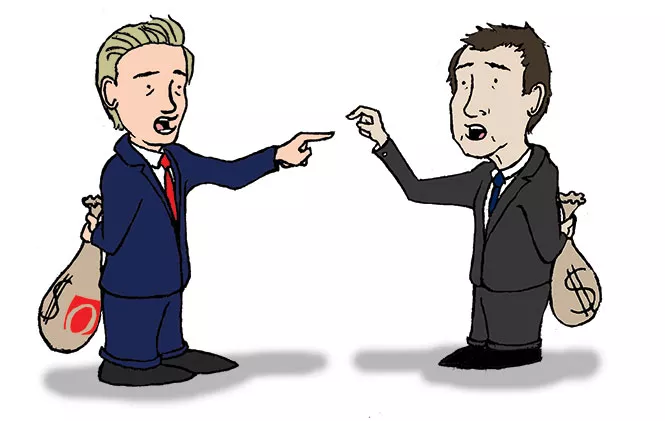

As each campaign points a finger at the other, though, an uncomfortable truth about the activities of both campaigns is the fact that each are operating well within the boundaries of Utah's unbridled campaign finance laws—laws that neither candidate seems eager to change, even as they bemoan one another's tactics.

"They're both saying what the other guy is doing is bad, but what I'm doing is fine," Burbank says.

As governor, Herbert has been a cheerleader for Utah's unfettered campaign contribution laws. And a yearly effort by House Minority Leader Rep. Brian King, D-Salt Lake City, to place a cap on contributions, is a perennial failure at the Legislature.

King's latest bill, HB60, would have placed a $20,000 limit on contributions from individuals, corporations and unions to candidates running for a statewide office. The federal government's cap on contributions to candidates is $2,700. In Salt Lake City, mayoral candidates can receive a maximum of $3,500 from donors, while City Council candidates can rake in $750.

One reason King says his colleagues in the Legislature and others around the country often oppose a cap on fundraising is the well-protected right of an individual to give as much of their own money to get themselves elected.

Although many cities, counties and states, as well as the federal government, have placed caps on the amount of money individuals and corporations can contribute, there are no laws prohibiting how much a person can give to their own campaign. This method—self-financing—is occurring on the Democratic side of the governor's race, where the majority of Michael Weinholtz' cash has arrived in the form of a $1-million check he wrote.

Between Weinholtz, Herbert and Johnson, a trio of fundraising tactics is on display, says Marty Carpenter, Herbert's campaign manager.

"Most people seeking office have to go and raise money from a broad group of people," Carpenter says. "The governor's not a man of independent wealth. He's got to go that third route."

While Carpenter insists that neither he, nor the governor, has insinuated that Johnson has done anything illegal by accepting such large checks from his boss, he says voters should consider the donors' possible motives.

"It's just common sense that if it's one person, that is the entire funding mechanism, that there's going to be more potential for that person to influence decisions in that administration," Carpenter says.

Johnson's campaign did not respond to questions about campaign finance.

While Carpenter and Herbert point to the possibility that money can buy political influence, it was Herbert who put words to it during his April fundraising pitch to lobbyists. Although the governor insisted there would be no quid pro quo with regard to donations, he was promising access to top donors, even going so far as telling the lobbyists, "I think on balance, we're giving you the results that you want."

While Carpenter says the volume of contributors is important to shield undue influence, it is easy to look at Herbert's list of large contributors and see that many have achieved lucrative gains in Utah. For instance, Bowie Resource Holdings LLC, has given $29,000 to various Utah leaders, $14,000 of which went to Herbert. During the 2015 Legislature, state leaders agreed to spend $53 million to build a coal port in Oakland, Calif., that would be operated by Bowie.

Did Bowie's campaign contributions pave the way for use of Utah money on its coal port? It's a tough question, but one that could be posed for any one of the numerous donors who have written Herbert $25,000 checks, and can certainly be asked of Overstock.com's Byrne.

Weinholtz is the rare candidate who hasn't been forced to drink from the corporate trough. In self-financing his campaign, he says he's been able to uphold a personal value: that large campaign contributions often take on the appearance of a conflict of interest. And so Weinholtz has declined to accept any contributions from corporations, and, at the end of the day, it is his own financial largess that carries his political efforts.

If Weinholtz is elected, he says he would support campaign finance reform in Utah, and says a cap of $10,000 on individual donations would be prudent.

His bickering Republican opponents, he says, are each a good example of how Utah's campaign finance and conflict-of-interest laws are broken.

"I think it reveals that Utah campaign-finance laws, and ethics laws for that matter, are rated fairly poorly in large part because we do not have caps on campaign contributions and that can lead to the kind of issues that both Governor Herbert and Jonathan Johnson are accusing each other of," Weinholtz says.

And although Weinholtz, a businessman who is chairman of the board of the physician staffing company CHG Healthcare, might be rich, he says that by not begging money off of other rich people, he hopes to be a voice for the millions of Utahns who don't contribute to campaigns. "The reason I wanted to largely self-fund is because I want to be a voice for the people of Utah who don't have a voice and they can't afford to write a big check to the governor to get their concerns heard," Weinholtz says.

While Burbank believes it's unlikely that Utah's liberal campaign finance laws will change anytime soon, one election outcome—a Democratic winning a state office while exploiting Utah's liberal laws—could spark action.

"As long as it's kind of all on the Republican side, I suspect that there's not really going to be a big appetite for making that change," Burbank says.