- Slug Signorino

Has anybody tried to assign a monetary value to the moon? If so, did they only take the mineral value into account, or did they include the many services the moon provides, such as the tides and enough light not to walk into signposts at night? —Matt Wheeler, Salt Lake City

Give me a break, Matt. The moon isn’t just some rock sitting out there, it’s metaphysical. It’s what watches over your first kiss on a spring night, the guide to every seafarer drifting on the lonely ocean who was too cheap to buy a GPS, and the thing that gives werewolves their special joie de vivre once a month. You can’t assign it a monetary value.

You say: Spare me. It’s 2012 and you can assign a value to anything. Somewhere out there, a 19-year-old YouTuber has just signed a Hollywood development deal based on raw footage of her fish tank. Who says you can’t monetize the moon?

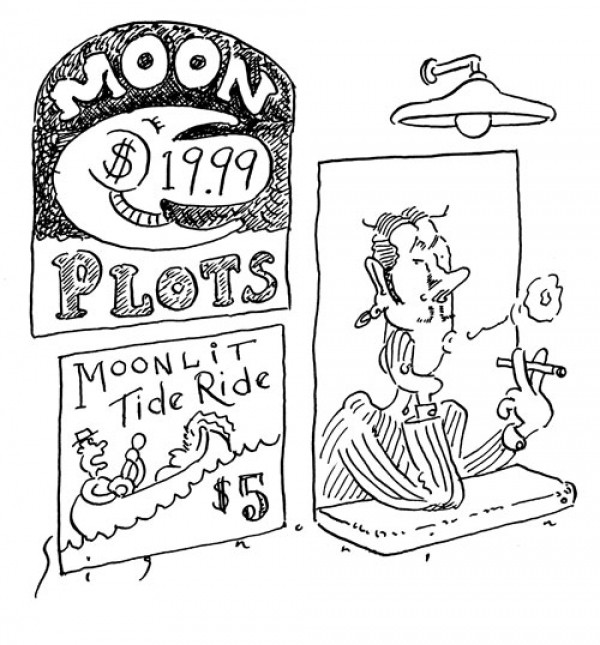

I acknowledge the truth of this. Let’s see. A company called Lunar Embassy, using the Brooklyn Bridge method of real-estate valuation, has sold more than 2.5 million one-acre moon plots, currently priced at $19.99 each plus $1.51 “lunar tax” and $12.50 “shipping and handling” for your “deed.”

Given a lunar surface area of 9.37 billion acres, and assuming a profit of $21.50 per acre, we’re looking at just over $200 billion in value. No wonder the company’s founder has warned world governments not to trespass on “his” moon and is fighting the International Monetary Fund to get a phony moon currency recognized.

Too flaky for you? Let’s look at a few other schemes:

Mining. The draw is the same thing that attracts asteroid prospectors, discussed previously in this space—platinum group metals plus gold. Due to eons of asteroid impacts, the moon’s surface contains appreciable amounts of these elements, which go for upwards of $1,000 per ounce.

The prospect of lunar mining is compelling enough that Google is funding a $30 million Lunar X-Prize for the first private group to land a robot on the moon, explore the surface, and send back high-res images. However, you’ve got all the problems of mining asteroids, plus the fact that the moon isn’t nearly as rich in valuable metals—we’re talking parts per billion. You’d need to mine about 1,300 tons of rock to collect one troy ounce. Prices would have to rise to, well, astronomical levels for such a venture to be profitable. I could cook up some theoretical valuation for lunar metals, but as a practical matter they’re worth zip.

Energy. A possibly more useful lunar resource is helium-3, an isotope rare on Earth but relatively abundant on the moon. Helium-3 is part of the solar wind that has buffeted the solar system for billions of years. Since the moon has no magnetic field or atmosphere to speak of, helium-3 atoms aplenty have become embedded in its surface.

What makes helium-3 potentially important is that it’s an ideal fuel for nuclear fusion, which some believe could generate enormous amounts of clean, cheap energy. Just 40 metric tons of helium-3—about what would have fit in the cargo bays of two of our now-defunct space shuttles—could supply the world’s electrical needs for three months, giving helium-3 a value of about $14 billion per ton. A million-plus tons of helium-3 are thought to litter the lunar surface—about $13.6 quadrillion worth.

Except for the usual problems. One, we have no idea when fusion will become a viable energy technology. Two, we lack a cost-effective way to collect lunar helium-3 and get it back to Earth.

Moonlight. My assistant Una devised a spreadsheet purporting to show that the replacement value of moonlight, understood as the cost of the energy needed to generate equivalent illumination, was $33 billion per year. I acknowledged her ingenuity but pointed out that, inasmuch as moonlight performed no measurable work, its replacement value was nil. This led Jim, the Straight Dope copy editor, to note that forward-thinking economists often impute value to intangible quality-of-life factors and that as a contributor to human well-being, moonlight could be assigned a value, too.

I didn’t buy it. I conceded that from a real-estate standpoint, the moon was an amenity hypothetically adding to the Earth’s resale value, but maintained that absent any competing habitable planets this had no practical effect. As for whatever sense of well-being moonlight might impart, one could achieve comparable results with Scotch. Monetary value: $0.

Energy, part two: tides. This one is almost plausible. The moon causes the tides. In most coastal regions, tidal energy is too diffuse to be harnessable, but in locations such as fjords, straits and estuaries, where the water sluices through a channel, one might construct tide-driven generators to capture the flow’s energy and convert it to electricity. Conservative computation of annual revenue: $31.5 billion, if—big if—tidal generators were ever built.

To sadly summarize: While the theoretical value of the moon may be countless zillions, today it’s not worth jack.

Send questions to Cecil via StraightDope.com or write him c/o Chicago Reader, 350 N. Orleans, Chicago 60654. Subscribe to the Straight Dope podcast at the iTunes Store.