On Feb. 24, 2011, federal agents simultaneously raided the telemarketing offices of Ivy Capital Inc. in California, Utah and Nevada. Prosecutors for the Federal Trade Commission would later charge the businesses for defrauding thousands of Americans out of $40 million.

Headquartered in Las Vegas, Ivy Capital worked with several Utah offices. One of them, Fortune Learning LLC, which provided coaching services for Ivy Capital, was located in a nondescript office in an American Fork business park. While the premises easily could have been mistaken for a dentist’s office or a print shop, Fortune Learning, along with its principal, Steven Sonnenberg, as well as Orem-based Wholesalematch.com were, according to an FTC complaint, part of an enterprise of 22 companies that worked like a pack to defraud consumers wanting to invest in online-business opportunities.

Ivy’s companies allegedly promised consumers help in setting up their own Internet businesses, telling them they could easily earn $10,000 a month working only five to 10 hours a week, according to the FTC’s March 2011 complaint. Instead, according to the complaint, consumers were signed up with coaches who lacked expertise and gave simplistic help to consumers. Furthermore, companies often refused to issue refunds and frequently failed to disclose consumers of their three-day right to have their money refunded.

The government’s complaint says that, in some cases, in the middle of a high-pressure sales pitch, a company salesperson would e-mail the consumer a contract and rush them into providing an electronic signature.

These companies allegedly worked in tandem, selling consumers and then upselling them on costly additional services. Instead of consumers staking their claim to Internet wealth, however, many wound up being charged as much as $20,000 on their credit cards with little to nothing to show for it.

The Ivy Capital group of companies was swept up in the FTC’s “Operation Empty Promises.” While the case is ongoing in Nevada district court, the FTC also successfully froze the assets of the companies over concerns they were hiding money in a number of shell corporations. The case represents the third-largest alleged telemarketing fraud ring with major Utah ties the FTC has cracked down on in recent years after charging companies including Mentoring of America and affiliates in 2009 and Jeremy Johnson’s IWorks in 2010. Even still, word of the raid and the case against Ivy’s companies received little attention in the local media.

Since 2009, Jason Jones has chronicled the legal troubles of numerous companies operating in the online-business-opportunity (OBO) industry on his website, SaltyDroid.info. Jones says the media has failed to grasp how some companies in the industry gang up and work like packs of predators feeding on individual clients to extract the most money possible out of them.

“It’s hardly been reported on at all how much these guys work to share names, how much this is like an enterprise and not some random association of thousands of bastards,” Jones says.

In a 2011 receiver’s report, government investigators quoted an individual whose elderly mother was hit with $16,000 on her credit card by Ivy companies. “You took advantage of trusting people,” the individual complained, referring to Ivy companies. “You gave them false hope. You lied to them and then turned around and ignored them as soon as you got those credit-card numbers.”

Hard-Selling Days

Utah’s former U.S. Attorney Brett Tolman returned from public office in 2009 to private practice. Moving from prosecution to corporate law, Tolman says, he saw an opportunity to help Utah’s OBO industry “grow up.”

It was during this time that online-business-opportunity companies, from sales floors selling consumers on coaching services to the fulfillment companies providing the coaching noticed things were changing. Credit-card companies were beginning to crack down on OBO companies because of an ever-increasing volume of “chargebacks,” refunds demanded by unhappy consumers disillusioned by the hard-selling companies that broke consumer-protection laws by overstating the earning potential of online businesses.

In 2009, the FTC charged a number of companies, including Utah-based call center Mentoring of America, for running a massive scheme. In May 2012, the FTC won its case against the company and is now seeking $450 million from the companies for defrauding over a million consumers.

Returning to the private sector, former U.S. Attorney Tolman began cultivating telemarketing clients and helping them understand that surviving in the industry means being willing to be scrutinized by state and federal regulators—not hiding from them—and not counting on political donations to buy them protection.

“I was making a pitch to a lot of these companies that they should start to become real strong and grown-up companies and businesses,” Tolman says. His policy was to drill the need for compliance into his clients, even getting one company to create training and certification programs for its coaches, imposing compliance audits and requiring coaching companies to make sure they vet the sales floors they work with and impose stringent standards on sales-floor partners, as well.

“This is a $4 billion industry, and it’s not going to go anywhere,” which means that if it’s going to survive, it has to deliver on its promises, Tolman says. Part of the problem, he says, is that some companies have the wrong idea about how to deal with regulators and the state Attorney General’s Office.

Sold Up

A fair chunk of the change to be made by OBO industry players comes through upsells (See “The Telemarketing Food Chain” on p. 28). Companies that sell consumers on an opportunity to start a business may then pass their client’s information onto “upsell” companies that may hit the client up for extra services.

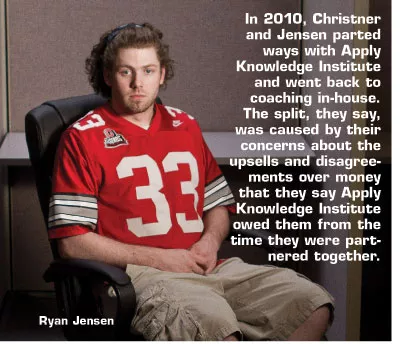

Aaron Christner, an embattled former telemarketer, says a disagreement over upsells with former partner Apply Knowledge Institute helped put his company in the crosshairs of the Utah Division of Consumer Protection. In 2011 his company was fined $400,000 for operating a call floor for three months in 2010 without being properly bonded or licensed.

Both Aaron Christner and business partner Ryan Jensen look like the sort of businessmen who seldom have to deal with customers in person. They work in torn jeans, T-shirts and ball caps; Jensen is 27 and Christner is 34. By the looks of the two, you’d never guess they had run a business that cleared $8 million in sales in a few short years.

Christner is an Ohio native who got a job dialing at a sales floor in St. George, where he met Jensen. They were both “setters”—call-center marketers who would set clients up with coaching services. Christner and Jensen’s jobs basically were to dial “leads” or contact info for customers and sell them a coaching product. If they signed up, the customer was then punted to the coaching company, which trained them on online-business opportunities.

“I was like, damn, is that all there is to it? You get leads and sell somebody else’s product?” Christner recalls. The two men eventually opened up their first floor, Diverse Marketing, in Salt Lake City in 2008.

Selling during the early days of telemarketing—before a number of bad actors in the industry brought heat from regulators and credit-card companies—the men profited, but also felt that their company would do better to offer its own in-house coaching.

Christner and Jensen talk about an ongoing feud in the industry over which businesses were the cause of consumer complaints. The men say their clients would blame them if the coaching company they referred them to sold them on additional services, presented to clients as necessary for them to really make money.