On Feb. 24, 2011, federal agents simultaneously raided the telemarketing offices of Ivy Capital Inc. in California, Utah and Nevada. Prosecutors for the Federal Trade Commission would later charge the businesses for defrauding thousands of Americans out of $40 million.

Headquartered in Las Vegas, Ivy Capital worked with several Utah offices. One of them, Fortune Learning LLC, which provided coaching services for Ivy Capital, was located in a nondescript office in an American Fork business park. While the premises easily could have been mistaken for a dentist’s office or a print shop, Fortune Learning, along with its principal, Steven Sonnenberg, as well as Orem-based Wholesalematch.com were, according to an FTC complaint, part of an enterprise of 22 companies that worked like a pack to defraud consumers wanting to invest in online-business opportunities.

Ivy’s companies allegedly promised consumers help in setting up their own Internet businesses, telling them they could easily earn $10,000 a month working only five to 10 hours a week, according to the FTC’s March 2011 complaint. Instead, according to the complaint, consumers were signed up with coaches who lacked expertise and gave simplistic help to consumers. Furthermore, companies often refused to issue refunds and frequently failed to disclose consumers of their three-day right to have their money refunded.

The government’s complaint says that, in some cases, in the middle of a high-pressure sales pitch, a company salesperson would e-mail the consumer a contract and rush them into providing an electronic signature.

These companies allegedly worked in tandem, selling consumers and then upselling them on costly additional services. Instead of consumers staking their claim to Internet wealth, however, many wound up being charged as much as $20,000 on their credit cards with little to nothing to show for it.

The Ivy Capital group of companies was swept up in the FTC’s “Operation Empty Promises.” While the case is ongoing in Nevada district court, the FTC also successfully froze the assets of the companies over concerns they were hiding money in a number of shell corporations. The case represents the third-largest alleged telemarketing fraud ring with major Utah ties the FTC has cracked down on in recent years after charging companies including Mentoring of America and affiliates in 2009 and Jeremy Johnson’s IWorks in 2010. Even still, word of the raid and the case against Ivy’s companies received little attention in the local media.

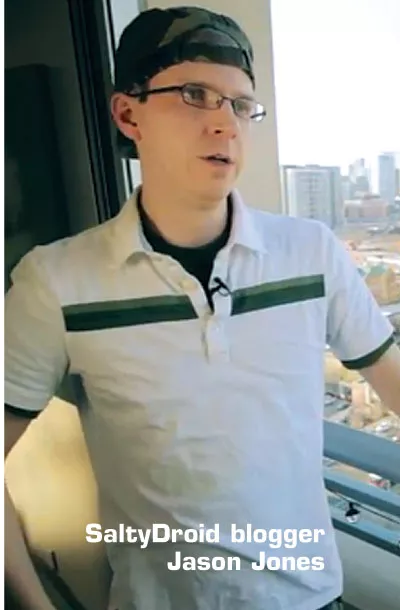

Since 2009, Jason Jones has chronicled the legal troubles of numerous companies operating in the online-business-opportunity (OBO) industry on his website, SaltyDroid.info. Jones says the media has failed to grasp how some companies in the industry gang up and work like packs of predators feeding on individual clients to extract the most money possible out of them.

“It’s hardly been reported on at all how much these guys work to share names, how much this is like an enterprise and not some random association of thousands of bastards,” Jones says.

In a 2011 receiver’s report, government investigators quoted an individual whose elderly mother was hit with $16,000 on her credit card by Ivy companies. “You took advantage of trusting people,” the individual complained, referring to Ivy companies. “You gave them false hope. You lied to them and then turned around and ignored them as soon as you got those credit-card numbers.”

Hard-Selling Days

Utah’s former U.S. Attorney Brett Tolman returned from public office in 2009 to private practice. Moving from prosecution to corporate law, Tolman says, he saw an opportunity to help Utah’s OBO industry “grow up.”

It was during this time that online-business-opportunity companies, from sales floors selling consumers on coaching services to the fulfillment companies providing the coaching noticed things were changing. Credit-card companies were beginning to crack down on OBO companies because of an ever-increasing volume of “chargebacks,” refunds demanded by unhappy consumers disillusioned by the hard-selling companies that broke consumer-protection laws by overstating the earning potential of online businesses.

In 2009, the FTC charged a number of companies, including Utah-based call center Mentoring of America, for running a massive scheme. In May 2012, the FTC won its case against the company and is now seeking $450 million from the companies for defrauding over a million consumers.

Returning to the private sector, former U.S. Attorney Tolman began cultivating telemarketing clients and helping them understand that surviving in the industry means being willing to be scrutinized by state and federal regulators—not hiding from them—and not counting on political donations to buy them protection.

“I was making a pitch to a lot of these companies that they should start to become real strong and grown-up companies and businesses,” Tolman says. His policy was to drill the need for compliance into his clients, even getting one company to create training and certification programs for its coaches, imposing compliance audits and requiring coaching companies to make sure they vet the sales floors they work with and impose stringent standards on sales-floor partners, as well.

“This is a $4 billion industry, and it’s not going to go anywhere,” which means that if it’s going to survive, it has to deliver on its promises, Tolman says. Part of the problem, he says, is that some companies have the wrong idea about how to deal with regulators and the state Attorney General’s Office.

Sold Up

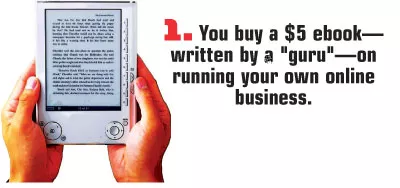

A fair chunk of the change to be made by OBO industry players comes through upsells (See “The Telemarketing Food Chain” on p. 28). Companies that sell consumers on an opportunity to start a business may then pass their client’s information onto “upsell” companies that may hit the client up for extra services.

Aaron Christner, an embattled former telemarketer, says a disagreement over upsells with former partner Apply Knowledge Institute helped put his company in the crosshairs of the Utah Division of Consumer Protection. In 2011 his company was fined $400,000 for operating a call floor for three months in 2010 without being properly bonded or licensed.

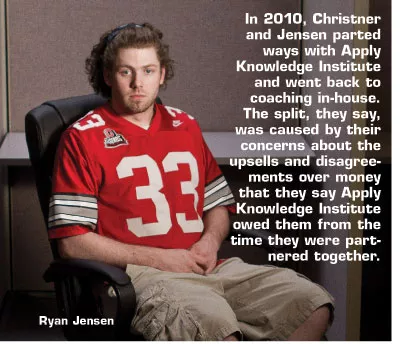

Both Aaron Christner and business partner Ryan Jensen look like the sort of businessmen who seldom have to deal with customers in person. They work in torn jeans, T-shirts and ball caps; Jensen is 27 and Christner is 34. By the looks of the two, you’d never guess they had run a business that cleared $8 million in sales in a few short years.

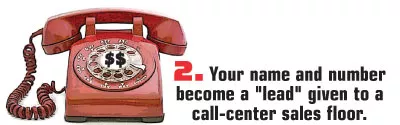

Christner is an Ohio native who got a job dialing at a sales floor in St. George, where he met Jensen. They were both “setters”—call-center marketers who would set clients up with coaching services. Christner and Jensen’s jobs basically were to dial “leads” or contact info for customers and sell them a coaching product. If they signed up, the customer was then punted to the coaching company, which trained them on online-business opportunities.

“I was like, damn, is that all there is to it? You get leads and sell somebody else’s product?” Christner recalls. The two men eventually opened up their first floor, Diverse Marketing, in Salt Lake City in 2008.

Selling during the early days of telemarketing—before a number of bad actors in the industry brought heat from regulators and credit-card companies—the men profited, but also felt that their company would do better to offer its own in-house coaching.

Christner and Jensen talk about an ongoing feud in the industry over which businesses were the cause of consumer complaints. The men say their clients would blame them if the coaching company they referred them to sold them on additional services, presented to clients as necessary for them to really make money.

As soon as Christner and Jensen sold a client on a $4,000 coaching package, for example, they referred the client to Apply Knowledge Institute. From there, Christner says, clients would get upsold on services like tax preparation and additional marketing and mentoring. “Clients were coming back and saying, ‘I’ve paid $15,000, and I haven’t made any of my money back,’ ” Christner says.

He feels coaching companies in the industry, in general, can push clients too hard on upsells. “You got people right now selling $15,000 to $20,000 coaching programs, and their clients are not making a dime,” Christner says. “You could buy a Wienerschnitzel [restaurant] for $20,000. You might not like selling hot dogs, but at least you’re making money.”

The pair tried to team up with a friend in the industry, Josh Reynolds—who was also dialing for Apply Knowledge Institute. Reynolds says that for having a small floor, he couldn’t keep up with all the clients calling him upset over the coaching and upsells they had received from Apply Knowledge. “I asked them to stop, and it just got sneakier,” Reynolds says. His pleas were basically ignored despite him asking coaches to “be nice to my clients. The money’s not going anywhere. Can we make them a little money before we start upselling them?”

The three men say that because sales floors are often customers’ first point of contact, when customers are unhappy, they may not realize they are dealing with another company for the coaching services and will blame the sales floors. In 2010, Christner and Jensen parted ways with Apply Knowledge Institute and went back to coaching in-house. The split, they say, was caused by their concerns about the upsells and disagreements over money that they say Apply Knowledge Institute owed them from the time they partnered together.

Apply Knowledge Institute’s owner, Ken Sonnenberg—brother of Fortune Learning’s Steven Sonnenberg—disagrees. He says he parted ways with Jensen and Christner because of the salesmen’s business practices. Ken Sonnenberg says their business repeatedly made earnings claims to customers over the phone—an illegal practice of overpromising how much money can be made by purchasing the program.

“Time after time, I just caught them doing stuff dishonestly,” Ken Sonnenberg says. “It hurt me in the long run. They ended up owing me about $30,000”—a charge Christner and Jensen deny.

Christner and Jensen were fined $400,000 in March 2011 for telemarketing without a proper bond for a three-month period in 2010. Francine Giani, the executive director of the Utah Department of Commerce, says the consumer protection division rarely collects judgments that large but also says Christner and Jensen evaded investigators and avoided compliance.

Christner and Jensen, however, feel the division pursued them with a vendetta and that they were especially wary when they heard former business partner Apply Knowledge Institute gave information to regulators about their business in a December 2010 hearing. While a transcript from the hearing notes Ken Sonnenberg discussed Christner and Jensen with Consumer Protection, Sonnenberg says he provided no information to the state about consumer complaints or about their bond status.

The two also struggle to understand how the state’s hammer came down on them so hard over a bonding issue. They note another company, JNJ Consulting, misled the division but avoided serious consequences.

Duped

“Ted,” a 70-year-old retired Wall Street recruiter living in New York state, who asked that his real name not be used, says that in 2010, he got taken by a slew of Utah companies that worked together like a wolf pack, using high-pressure sales tactics that quickly helped relieve the New Yorker of $9,250.

“I have an MBA, but even I got duped,” Ted says.

Ted says that after his own business slowed down in 2010, he decided to try selling musical instruments through an Internet shipping service offered to him after signing up with JNJ Learning, a Utah company that, unbeknownst to Ted, nearly had its telemarketing license revoked in 2010 for failing to disclose the owners’ criminal records. Ted says the JNJ telemarketer kept pressuring him, urging him to make a decision by the end of the phone call. If he wanted to prosper, he had to put his money where his mouth was. Ted says he was never told he had three days to cancel and get a full refund—a violation of Utah telemarketing laws.

The company that provided what Ted called “extremely simplistic” coaching was Apply Knowledge Institute, which, since 2009, has contracted with JNJ to sell its products. Owner Ken Sonnenberg says he never talked to Ted and says that his understanding was that Ted received months of coaching and never complained to the company about the service. Apply Knowledge Institute has no record of administrative actions from either Utah or federal regulators.

Terry Waller, a 63-year-old retired truck driver from Florida, got sold on coaching services by JNJ in 2010, and while he can’t recall the name of the company that did the coaching for him, he remembers that it was less than helpful.

“I thought they were going to hold my hand a little bit,” Waller says. “But they just threw me to the wolves after they got my money.” Waller paid roughly $2,000 for the coaching he was sold on and says he was never told about his refund rights, either. For the amount of money he lost, he says, it wasn’t worth consulting a lawyer. “I would have to go through all sorts of litigation to get it back, so I didn’t even try,” Waller says. “I got sucked in, and that’s that.”

Waller wasn’t the only one who got sucked in. You might say the state of Utah also felt duped when it discovered in 2010 that JNJ principals omitted information on their telemarketing application about their criminal histories.

Street Crime Doesn’t Pay

The Utah Telephone Fraud Prevention Act of 1993 specifically restricts prison inmates from telephone solicitation. However, at least one Utah OBO coaching company had no qualms about hiring workers with criminal backgrounds—especially since the owners themselves had such backgrounds. Nic Johnson and Jeff Nielson, principals behind the company JNJ Consulting, each have criminal records.

In 2010, Consumer Protection temporarily revoked JNJ’s license since the company application stated that none of its owners, managers or key employees had criminal records. Johnson was charged with burglary in 2003. In a February 2003 probable-cause statement, a Midvale City Police detective wrote that a resident came home to find a truck parked in her driveway. When she went in, she found she had been robbed of jewelry, power tools and a computer. Johnson was spotted leaving the scene and quickly apprehended by police. Johnson avoided trial, pleaded guilty and completed probation in 2006. The felony-burglary charge was reduced to a misdemeanor in 2007.

Jeff Nielson, who would later become Johnson’s partner in JNJ, has a more checkered history. Between 2004 and 2005, Nielson faced 32 criminal charges, including felony and misdemeanor charges from crimes committed in Fillmore, Provo and Salt Lake City. The allegations ranged from forging an $80,000 check to snatching the purse of a woman loading groceries into her car at a West Jordan Smith’s. Nielson was found guilty on 10 felony charges in 2005. He avoided trial by entering court-ordered drug treatment and paying restitution to victims. By 2006, he had completed probation on all charges.

Both men rehabilitated and moved on with their lives … into the OBO industry.

The men only got in trouble in 2009 when Consumer Protection found their histories left off their telemarketing application.

Despite repeated attempts, City Weekly was unable to contact Nielson and Johnson for this story. But according to a Consumer Protection administrative finding of fact from April 2010, Johnson asserted that not disclosing his criminal past “was not intentional” because he believed only felony convictions had to be disclosed and his burglary charge had been reduced to a misdemeanor. Consumer Protection also recognized that Nielson’s criminal background wasn’t an issue because “Nielson was not an employee of JNJ at the time Johnson completed and submitted the application.”

When JNJ faced losing its telemarketing permit in 2010, after a hearing with Consumer Protection, the company was simply required to pay a higher bond than usual and was allowed to continue operating.

Crawford Lindsay, an employee and former manager who worked for Johnson and Nielson from 2007 to 2009, describes the pair as Ultimate Fighting nuts, sporting gelled hair and rocking house music at the office. “They were more or less real Jersey Shore types,” Lindsay says.

Lindsay says he didn’t fully understand the nature of the industry until he got into management position and began hearing what he described as a high volume of customer complaints and requests for refunds. The real crime, Lindsay believes, was the product they sold customers on.

“These guys were selling shit in a box,” Lindsay says of the coaching packages they sold for various coaching companies. “I’m just as guilty, but I was told by the owners that [our customers] were being taken care of. It took me a while to realize, ‘Wow, I’ve probably sold millions of dollars worth of shit in a box, and I can’t ask one [customer] to show us how your business is going,’ ” he says.

Beyond that, Lindsay says, Nielson and Johnson ran no background checks on employees. One employee, Lindsay says, was hired right out of prison.

Calling

for Help

As Utah’s online-business-opportunity industry is growing, so, too, are concerns from regulators and advocates from within and outside the industry who wonder what can be done to clean up the industry’s troublesome practices.

For salesman Josh Reynolds, who, after six years in the industry, stopped running his own floor when he felt his clients were being unfairly upsold by the coaches of Apply Knowledge Institute, there is room for the industry to grow and profit while also making customers profitable.

“What I was pitched and raised on in the industry is that it was fun to help people. It was supposed to be about personal development, and you made good money doing it,” Reynolds says.

But the local industry’s efforts at self-policing have stumbled over the years. In 2009, an industry association called the Alliance for Lifelong Learning was formed to create standards for industry members, so that consumers would know OBO companies in the alliance could be held to higher standards than boilerplate operations that often run afoul of the law. That association, however, has since folded.

While several high-profile Utah telemarketing companies have been busted by the FTC for fraudulent practices, the Beehive State is not alone in its troubles with companies like Ivy Capital that allegedly swarm in on consumers in fraud attacks.

Amy Topol, the assistant director of Florida’s Division of Consumer Services, says her state’s legislature cracked down on telemarketers in the ’90s after many of the state’s population of retired citizens fell prey to unscrupulous salespeople.

In Florida, the businesses are regulated down to the individual telemarketers themselves, who have to be licensed with the state and are subject to criminal checks as part of their applications. This is to ensure they have not been convicted of crimes like theft or fraud.

“[Our staff] will arrest people if they are telemarketing without a license,” Topol says of repeat offenders.

She says the regulations have helped curb fraud in her state and also helped preserve the credibility of legitimate businesses that do comply.

“We feel that creating that level playing field helps out the ones acting appropriately,” Topol says. “One bad actor besmirches the whole industry.”

But The Salty Droid’s Jason Jones says all aspects of the industry—whether companies have had complaints, lawsuits or not—ask consumers to invest their time, effort and, especially, their money into business schemes that are just too good to be true. He doesn’t believe simple regulation can fix that. “I think you can make some money investing but you can’t make money doing this,” Jones says. “This is just a lie. You can’t regulate fraud.”

Tolman is hoping to carve a niche in the state’s OBO industry by guiding companies to focus on compliance and customer service, and not count on the political support of politicians. He sees the industry as here to stay. He says some companies need to learn the cost of doing legitimate business means setting as high of standards for its employees as the companies they partner with. Otherwise, they can expect to get hammered by regulators at one point or another.

“These companies need to decide to become legitimate, compliance-focused companies,” Tolman says. “They’re either going to learn it the easy way or the hard way.”

| Pack Attack Ivy Capital Inc. is one of a number of online-business-opportunity companies accused of working in fraudulent enterprises. According to a 2011 Federal Trade Commission complaint, the company, with offices spread across Utah, California and Nevada, allegedly defrauded thousands of consumers out of more than $40 million. The FTC alleges that to pull it off, the companies played hide & seek with consumers by utilizing 22 seemingly different companies that worked in tandem to sell consumers on developing their own online-business opportunities. While all money allegedly funneled into Ivy Capital, the companies often didn’t identify themselves to consumers other than to say they were part of the “success team.”

The team consisted of the following:

5 “control companies” that coordinated the companies’ pitches and handled money, including defendant Fortune Learning LLC with offices in American Fork and Provo

8 “upsell companies” that sold consumers on added services ranging from offering lines of corporate credit to tax preparation

2 “lead-generating companies” that culled contact information for potential customers through online ads and other means

7 “shell companies” that acted as front companies for the control businesses and coordinated the pitches

In addition, eight individual defendants were named in the complaint for coordinating the enterprise, including controlling member Steven Sonnenberg. Furthermore, in 2009, the Utah Division of Consumer Protection charged Ivy Capital’s American Fork office for running an unregistered telemarketing company. |