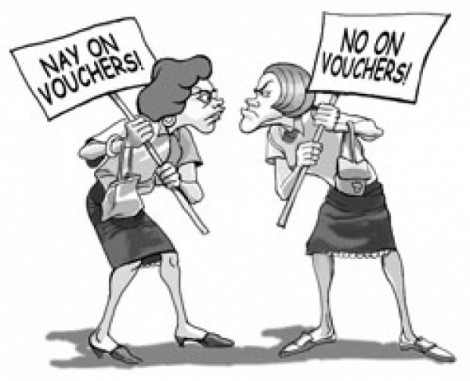

“There are issues that, on the national level, AFT and UEA are working together but, on the local level, we are not working together,” says UEA spokesman Mark Mickelsen. “They [AFT] certainly have not been visible in the voucher fight since the bill was passed in February.”

AFT may not be part of UEA’s antivoucher coalition Utahns for Public Schools, which includes the local NAACP and the League of Women Voters of Utah among others, but they are part of the fight against vouchers. “We are just as much fighting this referendum as anybody,” says Pat Fender, a labor representative for AFT.

Both unions are members of national organizations that have been at each other’s throats, off and on, since 1916 when AFT was formed. At the time, NEA had been around for more than 50 years. More recently, the two unions have made attempts at reconciliation—even merging in cities such as Los Angeles and San Francisco. But these national trends have not affected Utah. Ever since AFT began organizing in Utah in the early ’80s and broke UEA’s monopoly, a competitive environment has persisted.

“They don’t like the fact that we are cutting into their territory at all,” says retired schoolteacher Cliff Millward, AFT’s first member in Utah.

Despite AFT’s modest gains (its state membership stands at roughly 1,000), UEA is the dominant union with 18,000 members. Except for three school districts, UEA bargains on behalf of AFT teacher members across the state in any district where UEA holds the majority.

AFT attracts many disaffected UEA members, says Debbie White, AFT president. Formerly a UEA member, White defected because she felt its top-down structure didn’t react to the needs of teachers. Before leaving in 2000, she led a walkout of 3,500 teachers at the Granite School District protesting Utah’s abysmal public-school funding. UEA didn’t participate in the walkout. The split sent White to the AFT and drew a number of Granite School District UEA members into the AFT.

The difference between the two unions is mostly in their organizational makeups. AFT is controlled by its locals, so each local is different, says Liz Weight, union president for the Granite School District. AFT organizes all workers in the schools from bus drivers to janitors. UEA only admits teachers and accepts administrators as members. Also, as an “association,” UEA distances itself from the labor movement, whereas AFT is an active member of the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations.

Some AFT members list these differences as a rationale for leaving UEA. “I don’t think the UEA helps teachers that much,” says AFT’s Millward. “They have a very close relationship with many of the school districts and they don’t want that upset in any way.”

UEA’s Mickelsen doesn’t know why AFT has a following. “The idea of them being a legitimate part of the scene here never happened, and it’s not likely to happen.”

Recently, the competition flared up when the Legislature’s Senate Bill 56 passed in February. Backed by AFT and opposed by UEA, the bill’s passage allowed for broader organizing rules for all unions, not just the UEA, says Weight.

Mickelsen claims the original bill would have crippled collective bargaining in the state. The bill’s original wording would have forced school districts to bargain with every individual union represented in the district, even if that union only has one member.

Weight says the AFT only wants the ability to talk to teachers about their union, not destroy labor’s collective-bargaining power in the state. “Senate Bill 56 was about equal access,” she says.

How this discord will affect the voucher fight remains to be seen. For the present, the two unions are united in their voucher opposition—even if they don’t see eye-to-eye on everything else.

cw