Page 2 of 2

THE THING ABOUT THE TRUTH

At City Weekly’s request, UCASA’s Kindness reviewed Ripley’s case, including the responses of SLCPD to questions that identified four different versions of events she gave over a span of nine days following the rape, including her interview with a SANE nurse.

“The investigation is focusing on the behavior of the victim, not on the behavior of the suspect before and after the incident,” Kindness says. “Perpetrators of rape and sexual assault count on that, and this is why they target victims who are intoxicated or are otherwise in a vulnerable situation that will create obstacles for investigation and prosecution.”

One of those obstacles, says Valentine, is that a victim’s “memory gets so scattered by trauma, the perception by law enforcement is they’re just making it up.”

Defense attorney Andruzzi says that officers start “from the premise that the victim is lying and has to prove they’re telling the truth.”

That’s an expectation that former Utah County prosecutor Donna Kelly says is based on an erroneous view of how a victim should behave after a traumatic incident. Kelly has been training law enforcement, prosecutors and judges in victim-centered responses as part of a new, grant-funded position at the Attorney General’s Office.

“Professionals in the criminal-justice system—not just law enforcement—are trained to detect ‘lying,’ ” she says. “The problem is with sexual assault and domestic violence, they are interviewing people who have been traumatized. New research in the field of neurobiology shows that many of the signs law enforcement traditionally considered signs of lying are actually signs of trauma, but law enforcement doesn’t know that.”

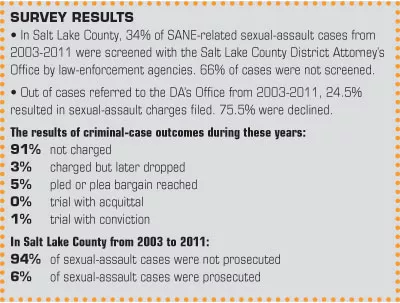

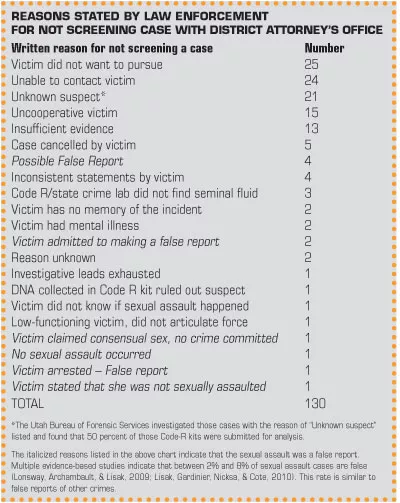

Of course, there’s “the elephant in the room,” as Valentine calls it in her presentation, of false reporting. The survey, in line with FBI crime statistics, shows that only 8 percent of the 130 cases were false reports.

But that doesn’t match some officers’ perspectives.

Sandy Police Department’s sex-crimes detective Andrea Hanson says the ratio of false reports of rape is higher than 1 in 10 as indicated by the survey.

She laughs darkly about a recent rash of “insane false reports. It’s very frustrating to put in months of work, you’ve done all this investigation, only to find the victim was lying,” she says.

Cara Tangaro was a sex-crimes prosecutor who now works as a defense attorney. She says she saw and sees many “buyer’s remorse” cases. She outlines a scenario where a woman would be dating, engage in sexual activity, ultimately have sex, see her LDS bishop, and then, a week later, report she’d been raped. “I had cases where people who had sex three or four times then reported it as rape.”

But sexual-assault responders argue that the perception of epidemics of false reporting stems from cultural myths.

“There’s a strong cultural holding in Utah that LDS women … engage in sex, then feel guilty, then wake up the next day and cry rape,” Mullen says. “That is a myth that continues to flourish and grow in Utah. [But] it’s an arduous, difficult, painful process to come forward to tell someone they’ve been raped. People don’t report rape just for the fun or it or just for attention.”

LEFT IN LIMBO

When Valentine presented her findings to the District Attorney’s Office, one of the shocked prosecutors turned to the DA’s victim advocate and asked her if it seemed accurate. She said yes.

“What none of us anticipated was that there were so many cases that were never actually brought and screened, that never even got to the point of declination,” says Salt Lake District Attorney Sim Gill.

But while he says the survey has value in the light it sheds on law enforcement, Gill rejects the picture it paints of his office’s low declination rate. “Those numbers don’t match up to the factual reality of what’s going on in the office,” he says.

Gill’s special-victims unit chief, Blake Hills, says the small sample size and the narrow focus of the survey—to assess the impact of SANE on rape prosecutions—have been misunderstood “by certain groups [who] are using them to make conclusions about declination rates for all cases.”

Valentine acknowledges that the annual declination rate on a year-by-year basis was debatable, but she notes that “the overall percentage of 75 percent declination is a more reliable finding, as it has a larger sample size,” namely all 90 referred cases.

One former sex-crimes investigator says part of the reason behind the low number of cases brought to the DA’s Office for screening is that cops get sick of filing cases that get turned down by the DA. The ex-investigator, who spoke on condition of anonymity, recalls detectives who would work for three years before they had “their first true adult rape. So many of them, you work your butt off, and the charges never come. It comes down to how you prove coerced against consensual sex. There’s a huge number of cases where alcohol is on board, and the physical findings get thrown out.”

Detectives, he continues, “don’t screen cases because so many get declined [that] they get sick of working their butt off to go in to hear ‘no’ in the end.”

SLCPD Chief Burbank questions the accuracy of the percentage of cases that the survey shows as not being screened—66 percent—as well as the DA’s assertion that law enforcement isn’t screening adult rape cases.

“I don’t think Sim’s office should be pointing fingers back at law enforcement, necessarily,” Burbank says. Detectives send cases to prosecutors for screening, he says, but are then told “it doesn’t sound like something we’re interested in going forward with,” so “there’s no official declination.”

He says one question that comes out of the survey is, “Are we doing all we can to move prosecution forward, are we applying enough pressure to the DA’s office to bring the case?”

The SANE survey shows that in two of the nine years, there were seemingly no—or very few—rape cases prosecuted. The survey also shows that for two years during former DA Lohra Miller’s administration—2009 and 2010—there was an uptick in the number of cases being filed and prosecuted.

After his 2010 election win, Gill disbanded Miller’s “boutique” prosecution units in favor of generalist prosecutors. This included, much to the dismay of sexual-assault responders, the domestic- violence unit headed by Michaela Andruzzi. Andruzzi complained of being marginalized by Gill, ultimately settling after a two-year fight with Salt Lake County over her treatment by his office.

Andruzzi—seen by some as deeply committed to justice for rape victims, and by others as overzealous—focused on intimate-partner-related rape cases and date-rape cases, which typically had gone to the special-victims unit. That resulted in a unit that became specialized in sexual assault as well as domestic violence. That, in turn, some detectives say, led to more confidence among law enforcement in screening sex cases.

Donna Kelly of the AG’s Office says that the “key is training; that’s the holy grail of sexual-assault prosecution.” In many other states, she notes, in contrast to Salt Lake County, prosecutors have gone to specialized units because of the intense level of training required.

It also requires personal commitment to a very demanding area of prosecution, where, Andruzzi says, a lack of motivation can derail a victim’s quest for justice or healing.

One victim advocate says that she gets multiple calls a week from survivors “who have no sense where their case is at, where they can get services,” having been left high and dry by the detective who put their case aside.

While Andruzzi says she tried to always tell victims personally why prosecutors were declining cases, there seems to be disagreement between officers and the DA’s Office over who is responsible for informing the victim if the DA declines the case.

“I call my victims, I don’t like leaving it to someone else to make the call,” says Sandy detective Hanson. But, she says, “the prosecutor is supposed to notify them. ... That wasn’t happening; we brought it up, and it was changed.”

But Blake Hills, chief of Salt Lake County’s special-victims unit, says, “It’s typically the detective who touches base with the victim to let the victim know what the decision was.”

Advocates say such a hit & miss system leaves many rape victims dangling in limbo. “Victims aren’t the easiest people to deal with,” says one advocate, “but to leave them with no recourse, direction or justice. … Just to hear the agony and loneliness in their voices, what do you do with that?”

What also dangles in limbo are many of the rape kits SANE nurses collect from victims. The survey revealed that half of the Code R kits in the 21 cases where no known suspect had been identified had not been sent to the Utah state crime lab for processing, meaning that DNA evidence of a rapist—potentially a serial rapist—gathered dust on department shelves.

FEAR OF THE DARK

As Valentine presented the survey to different audiences in law enforcement, the court system and sexual-assault responders, concerns quickly emerged about how rape victims, both past and future, would view the figures.

Valentine hopes the survey will not discourage victims to report rape and sexual assault. Rape, Valentine says, is about taking away control. “We want every victim who is raped to report. We want to provide care to them. This is their examination, and they’re in control.”

Unified Police Department Chief Jim Winder says he also hopes victims will always report. “When you’re victimized, the best approach is to begin to take back control, which means reporting,” he says. “Even in the eventuality that it isn’t prosecuted, hopefully, you’ve saved some other victim. I say dime every one of them out, report it, let us do our job.”

In order for a victim to heal, they first have to realize, Valentine says, that “they are the victim of a violent crime, and that they bear no responsibility for what happened.”

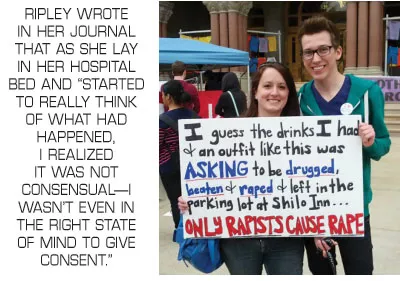

In spring 2013, Jessica Ripley took part in the SlutWalk, an annual march to the Capitol where women wear whatever they want—from bikinis to burkas—in an effort to dispel the myth that dressing modestly can prevent rape.

She held a sign on the walk that read, “I guess the drinks I had and an outfit like this was asking to be drugged, beaten and raped and left in the parking lot at Shilo Inn. Only rapists cause rape.”

But though Ripley immediately reported her Feb. 5, 2012, rape, she still struggles to move ahead. “I guess I’m expected to move on, to forget it ever happened,” she says. “I think about it honestly almost every day. You just don’t get over it.”

Memories of that night haunt her. She loathes the sight of the Shilo Inn, but can’t escape, she says, “that huge red building that glows at night.” Every night, she walks her dog, and every night, her fear of the dark reminds her of what an unnamed man brutally did to her.

“People always ask, ‘Why aren’t you dating, why aren’t you going out?’ ”

Her answer is two words, which she says with a slight smile: “I’m broken.”

WEST VALLEY CITY: LEARNING FROM MISTAKES

After West Valley Police Chief Lee Russo took over his agency five months ago, he authorized an audit of the department’s 260 sex-crimes cases from 2012. That audit found that in 10 cases, investigators’ claims that they had submitted them to the DA’s Office for screening were denied by the DA. Those cases have gone to Internal Affairs, which will investigate whether the officers were lying.

Of the three investigators in the unit, Russo says, one was terminated for unrelated misconduct, one subsequently resigned and one was reassigned to patrol. The supervisors were also reassigned.

In total, only 16 percent of West Valley’s sex-crimes cases were referred for prosecution, in contrast to the 34 percent county-wide shown by the survey. The deeper question, Russo says, is “why weren’t they being pursued?”

Russo says that “officers want to get as much of the story as quickly as they can to move the investigation forward. There are times when tunnel vision makes you forget about trauma, how the victim is perceiving it—we see it as just facts, get the investigation under way.”

That “impersonal professional perspective,” he continues, means that law enforcement “can become part of the problem with the victim, just one more overwhelming step in what happened to them.”

The survey should not be about pointing fingers, Russo says. Rather, “there’s an obvious problem and we have to fix that problem.” Law enforcement, prosecutors and victim advocates have to come together to define “how we make the system better for victims and hold offenders accountable.”

West Valley City is now taking point on trauma-awareness training in sexual-assault cases. It’s starting a one-year pilot program in January with the Attorney General’s Office’s Donna Kelly and WVC Detective Justin Boardman, training all WVC officers and detectives in the neurobiology of trauma. Valentine will measure the impact of training on both law enforcement and victims throughout the year.

She says this approach is so new that there is no literature available nationally on how to train a law enforcement agency in sexual-assault trauma.