It’s an unseasonably warm November morning, and something strange is happening at Wasatch High School.

The parking lots are packed to overflowing by 9 a.m., full of large four-wheel-drive trucks that are clearly work vehicles more than simple conveyances. That sight is not so unusual, given that the school’s rural Heber location means it serves kids living on ranches for miles around.

Look at the license plates, though, and there are trucks from Arizona, Wyoming, Nevada, Montana, Colorado and California joining those from Utah. Odd. And rather than fresh-faced young Utahns arriving to tackle algebra, football practice and all manner of daily teenage trials, the hundreds of people streaming through the school’s front doors are predominantly older males sporting one of the more impressive collections of drooping mustaches and wide-brimmed cowboy hats you’ll find outside a summer rodeo or Sam Elliott film festival.

They’re here for the Heber City Cowboy Poetry Gathering and Buckaroo Fair, an annual festival dedicated to all things Old West, from ranching prose to old-time music to the arts, crafts and tools endemic to the cowboy life. It’s the biggest gathering of its kind in Utah—one of the biggest in the country—and while Wasatch High’s students are on fall break each year, it turns the building into a buzzing showcase of a lifestyle largely forgotten—or never known—by urban dwellers along the Wasatch Front.

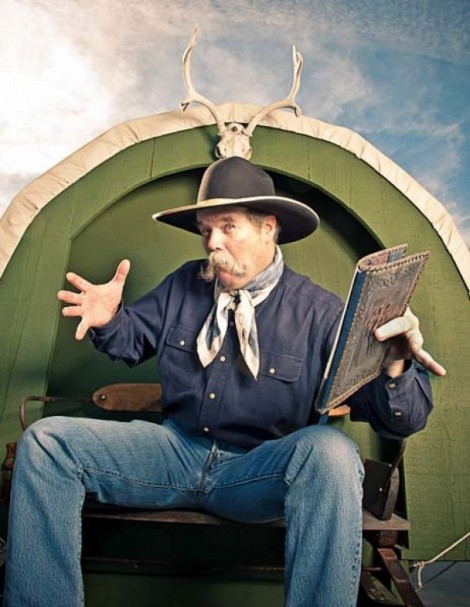

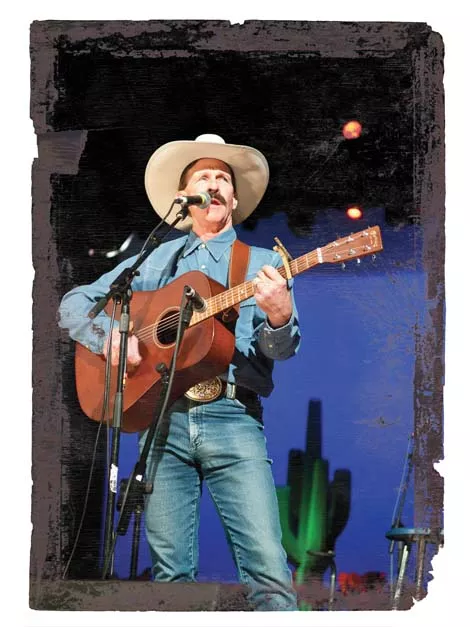

Go through the doors of the school, and the front hallways have been turned into essentially a mall for cowboys and cowgirls. You can buy some custom-fitted boots, ornate Western shirts and dresses or a saddle for your favorite horse back home. There are CDs of favorite poets and musicians, and an adjacent room serves up barbecue and sodas while a band of identically dressed players pluck out some bluegrass licks. The school’s gymnasium and various auditoriums have been decorated with cactus cutouts, old stagecoaches and other stereotypically Western imagery, and soon those stages will be filled by a who’s who of renowned cowboy poets and musicians. Among this year’s featured acts: rancher-turned-poet Waddie Mitchell, who’s hosted the Heber gathering for much of the past decade; Suzy Bogguss, a singer who’s shifting gears from the Nashville mainstream country scene to a more traditional Western sound; and a range of cowboy poets from Utah and beyond.

Spend some time at the Heber gathering, or at one of dozens of similar events across the country, and one gets the sense that cowboy poetry, prose and music are as thriving an art form as any other. But are these artists and their fans part of a booming—if retro—subculture, or are they simply the last gasp of an art form that will inevitably disappear along with the cowboy and ranching life?

The answer, for now, is that both ideas are true.

Cowboy Poetry Gets A Name

He first encountered what he’d come to know as “cowboy poetry” while doing field work for the Smithsonian Institute more than a quarter-century ago, when Cannon was roaming the Great Basin documenting the folk arts of the region.

“I’d talk to a cowboy one day, and then a quilter the next day, then maybe a fiddler the day after that,” Cannon recalls. “I met these real cowboys, and heard their wonderful stories and started exploring the poetry and how it reflected their real lives, and that had a big impression on me.

“I met Waddie Mitchell, guys who were working cowboys at the time [and later became prominent poets]. I ran into these sort of rumpled guys and started talking to them, and I really thought it was amazing. That was before any [cowboy poetry] events or anything, very insider, traditional. A lot of water’s gone under the bridge since then.”

Indeed it has: In the years since that first introduction to ranchers and cowboys waxing poetic about their horses, their buddies and their homes in the rugged, rural parts of the American West, Cannon has spent countless hours documenting the cowboy life.

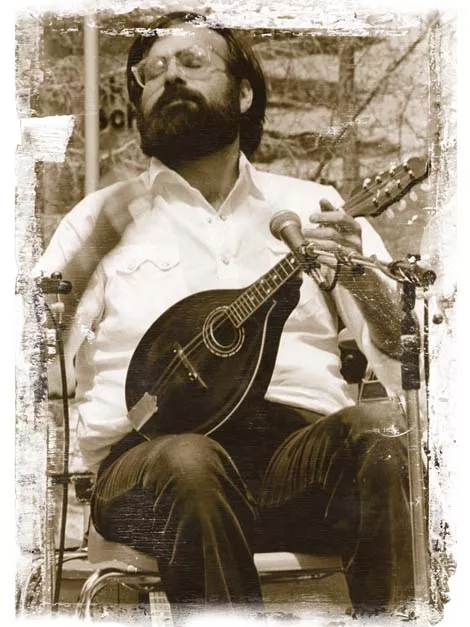

He was the Utah Arts Council’s first folk-arts coordinator in 1976, before starting the Utah- and Nevada-based Western Folklife Center in the mid-’80s. In addition to exploring Western life as an academic, Cannon has delved in as a filmmaker; Why The Cowboy Sings, a documentary he co-produced, aired nationally on PBS in 2003 and won a Rocky Mountain Emmy. And as a musician, Cannon led the long-running Deseret String Band, a group dedicated to researching and performing music found in the West in the 1800s, before leaving to join Red Rock Rondo, another group focused on traditional sounds and exploring the American West mythos.

It was while Cannon was working as the Utah folk-arts coordinator that he helped spawn the cowboy-poetry-gathering movement. He and his fellow Western-state folklorists held annual meetings in Logan at the time, and they would try to come up with ideas for joint research projects and grants they could apply for. After years of rejection, the National Endowment for the Arts finally gave the group a small sum to explore the poetry written and performed in the West’s ranching and farming communities.

The Elko gathering has since become known as the National Cowboy Poetry Gathering, and this January will mark its 27th year filling Elko’s hotels and casinos with poets, musicians, painters, chefs and folklorists obsessed with documenting and preserving the Western cowboy life.

While Elko is widely known as the granddaddy of cowboy-poetry gatherings, it is far from the only one these days. Across the West, cities like Santa Clarita and Monterey host large gatherings each year. And towns across Utah have hosted gatherings of their own, from Ogden to Kanab and many towns in between.

“From Salt Lake City’s perspective, it seems to me that Utah’s cowboy culture is not as strong an identifying force as it would be in Wyoming or Montana,” Cannon says. “And yet, there’s always been ranching and cowboys here. I went to a film premiere for a movie about saddle-bronc riding in Cedar City, and I looked around and it was all ranch folks.

“There are a lot of people who either make their living ranching or live in rural areas and identify with ranch culture. They may work delivering propane by day, but at night, they put on their cowboy belts and go out. Their identity is kind of ranch culture. You go out in rural Utah, that’s very prevalent.”

Those people make up the audience most likely to latch on to cowboy poetry and music for entertainment, but that audience is shrinking along with agricultural life in America. Roughly 90 percent of America was involved in ranching and agriculture during the late 1700s and early 1800s. A century later, that number was down to less than 50 percent.

And now, in 2010? Less than 2 percent of Americans make their living from the ranching and cowboy life. Yet cowboy-poetry gatherings continue to grow, blending traditionalists from rural communities with a new audience of urbanites yearning for a glimpse into a dying part of American life.