![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

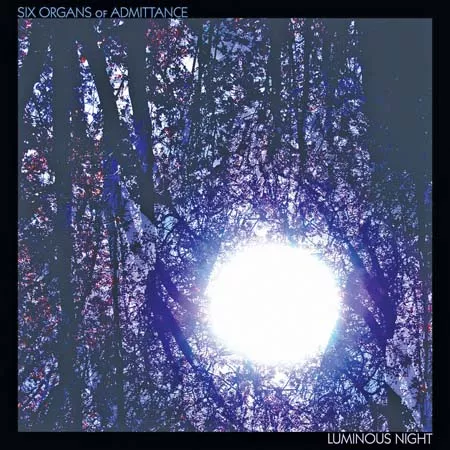

Six Organs of Admittance: Luminous Night (Drag City)

![]()

But, the sky provides an escape route, a path to somewhere else. “To leave any town, any time/a skill acquired from bein’ alone/only fixed to the stars as they twirl/around the tail of a bear like stone,” Chasny muses as guitar lines swirl above in imitation of birds. This leads into the “River of Heaven,” an Eastern-Indian influenced instrumental meandering river of sound, not necessarily joyous but elevated. The record doesn’t just illuminate, it enlightens. If this all sounds a bit too like a prog-rock concept album, it’s readily accessible.

Various Artists: Music For a Revolution (Arts Council England)

![]()

One of the most loaded words of the last century is “revolution,” a term embraced by pop musicians, most famously the Beatles, twice, with “Revolution” and “Revolution 9” in which John Lennon and Yoko Ono reworked the ending of the former song with the ominous voice intoning “Number 9,” one of the earliest examples of a remix.

This limited-edition collection, compiled by Alan Dunn, is a fascinating look at not only the musical uses of the word but also spoken-word samples, from The Cramps’ singer Lux Interior’s obituary to Aldous Huxley and Raul Castro, Marcel Duchamp, the terrorist Baader-Meinhof Gang and radio soccer broadcasts—diverse offerings that together indicate revolution has morphed into a ubiquitous symbol and a brand, the opposite of what most of its acolytes intended it to be.

Gil Scott-Heron’s iconic “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised,” the oft quoted and sampled elephant in the room, is not featured but cited as a cultural touchstone. Robert Pollard, the great ethnomusicologist of the sweeping-rock gesture, creates the ironic anthem “Headache Revolution.” The revolution may not be televised, and “the revolution will not be digitized,” according to Derek Horton on the sleeve notes, but this collection has traced the paths the word has taken in the course of a world revolving.