Page 3 of 3

HOODWINKED

Prosecutors

are not the only ones who didn’t want to talk about how Davies went

from being a “big deal” to a guy who spent only three months in prison

and got to keep one of his grow houses, while Angelos became a “violent

street gang” member who needed to be put away for life. Davies was

contacted multiple times for this story, but never consented to an

interview. He had two defense attorneys: John Caine, who died before the case was over, and Bernie Allen, who did not return multiple phone calls seeking a comment.

Part of the problems in Davies’ case may have been evidence. Daynes said during Davies’ sentencing hearing that “one of our warrants” concerned them and prompted the plea deal to Davies and Wagher.

But even Stephen McCaughey, the attorney who tried to suppress evidence on Wagher’s behalf, thinks the searches were legal. His best guess at what prosecutors worried about was the way in which the informant was granted anonymity.

More important than concerns about the warrant, McCaughey believes, was that prosecutors were disappointed with Davies’ and Wagher’s finances.

“I think [investigators] thought these guys were pretty good size, but when they executed the warrant, and sorted things out, Davies didn’t have a dime. Wagher had some property, but that’s not a bank account with hundreds of thousands of dollars in it,” McCaughey said.

Attorney Danny Quintana, who represented Wagher with an appeal that was eventually withdrawn, had a different view. Davies told the judge, for example, that the marijuana operation brought in only $1,000 per week, and neither the judge nor prosecutor challenged him on that claim— even though the police’s own estimates of Davies’ marijuana said one pound could garner $3,000. Quintana believes Davies fooled everyone. “He hustled the U.S. Attorneys, he hustled his probation officer, and he hustled the court. … Davies hoodwinked [Daynes]. He conned the system.”

Angelos feels Lazalde also fooled the system. Lazalde and Davies are now free men who cooperated, while Angelos and Wagher continue to serve their sentences.

TUNNEL VISION

Ohio State University law profesor Douglas Berman wrote a book and maintains a blog, both named Sentencing Law and Policy. While

he believes police and prosecutors “generally have the right instincts”

about which criminals are the worst offenders, occasionally big fish

turn out to be minnows. But because they’ve already invested their

limited resources, or because of their subconscious biases about race,

class or age, investigators can develop a “tunnel vision” in which they

scramble to find any facts to prove the original big-fish hypothesis.

“That’s the key idea: Once prosecutors commit themselves to a vision of a case and a defendant, it’s dangerously easy to push that vision forward, creating the kind of injustice we see in Weldon’s case,” says Berman, who is representing Angelos in his appeal.

University of Utah law professor Daniel Medwed agrees. A prosecutor “becomes more invested in the case. You spend time, prepare charges, prepare evidence ... so you’re beginning to develop a vested interest in the outcome.”

Rydalch says they do not discuss the screening process publicly. She also says it’s “wrong,” “frustrating” and “impossible” to compare the Davies and Angelos cases. First, the jury convicted Angelos of using a gun, which allowed prosecutors to seek mandatory consecutive 25-year sentences for those acts. Additionally, prosecutors believe Angelos was a violent gang member, though it should be noted that he was not charged with nor has he ever been convicted of any violent crimes. Third, Davies did, but Angelos did not, cooperate.

|

|

According to prosecutors’ brief to the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals, however, Angelos tried to cooperate with prosecutors but “the agents believed that Angelos had been untruthful regarding the source of his [marijuana] supply.” Was it that he was untruthful, as prosecutors believe? Or was he really just a little fish, as Angelos maintains?

On top of that, Berman thinks highstakes cooperation deals can be undermined by the worst criminals of all.

“The more sophisticated defendants know the guiltier they are, the more necessary it is to run to prosecutors to cooperate,” Berman says.

Angelos was offered a 16-year prison term in a plea bargain prior to trial, but when he turned it down, prosecutors filed a new indictment with more charges. This is a typical for federal prosecutors, Berman says. “I won’t discount the need and virtue of prosecutors to have these harsh terms to induce cooperation, but I will suggest the benefits of that in some cases, are radically outweighed by instances of rough justice [in other cases], where a person like Weldon is subject to a life sentence.”

Mandatory minimum sentences, which both Davies and Angelos faced, are only mandatory if prosecutors want them to be, says Cassell. The mandate is initiated by prosecutors and forces judges to do things they may not want to do.

“Mandatory minimums are a massive transfer of power away from the judicial branch to prosecutors in the administrative branch,” Cassell says. “They can decide to file these enhanced charges and drive the sentence by that. A prosecutor’s job is to apprehend and put away bad guys. Part of the reason for having a judge impose the sentence is we need checks and balances because prosecutors are trained to see the worst in people and argue that a long prison sentence is needed.”

Berman, Medwed and Cassell all support ending mandatory minimum sentences.

Medwed suggests the U.S. Attorneys Office “institutionalize” a formal review process whereby prosecutors would need to pitch their case to a panel of experts and gain their support before moving forward. Berman thinks judges should be involved when prosecutors want to reduce a defendant’s sentence for cooperation. Cassell advocates for a reinvigoration of the sentencing-guideline system that was created in 1975 to ensure similar criminals receive similar sentences. That system was declared unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court in 2005.

The U.S. Supreme Court has not, however, found that the 171 federal laws that carry a mandatory minimum sentence are unconstitutional.

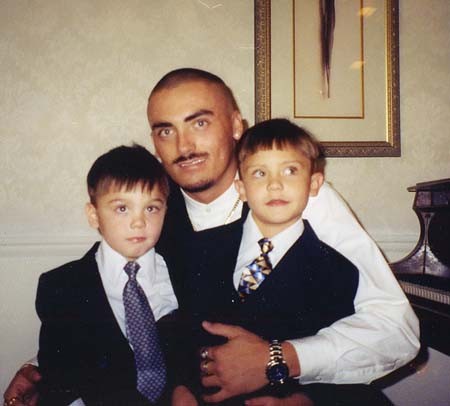

Angelos may seem like the biggest loser in this case, but his sister names at least three others hurt by the lengthy sentence.

“He

has two boys and a daughter. He’s never really met his daughter, other

than when she was a baby. He’s had interaction with her during [prison]

visits. Other than that, he’s never really known her. She was 6 months

old, or something like that, when he went to jail,” Lisa Angelos says

of her brother. “The boys were old enough to remember [their father].

They were severely impacted. … He was the sole provider for the family.

My husband and I play the role of Weldon at Christmas, but there’s

nothing that can replace him in their lives.”