John Saltas had been publishing The Private Eye newsletter for four years when he found himself in an uncomfortable place—the horse latitudes, stuck on a windless sea. He had just transitioned the paper from a direct-mail newsletter to a street publication. He was carrying debt, had only crumbs of operating capital and would lie awake most nights with anxiety. Truth be told, he was on the verge of calling it quits.

Hoping for inspiration, he found himself loitering in the library of the old University of Utah communication department, then located in the LeRoy Cowles building on Presidents Circle. Long graduated, he didn’t actually belong in that library, so when the librarian peered around the corner and asked if he needed help, he blindly reached for a magazine off the shelf and told her he was good.

His random choice turned out to be a magazine called Press Time, which featured an article about the Association of Alternative Newsweeklies (AAN), a trade group based in Washington, D.C., which in the late ’80s was made up of less than 40 newsweeklies. Thumbing through the article, reading interviews with founders of papers he’d long admired—the Chicago Reader, The San Francisco Bay Guardian, Denver’s Westword—Saltas had his epiphany (so much so that he made off with the magazine): Private Eye would one day be a peer to those publications.

First, though, he needed to join AAN—no easy feat, it turned out. AAN screens its members and only admits those that meet stringent standards (even today, the association has only 130 members). Papers must be general interest (as opposed to those that cater to music, gay issues, fishing, etc.); and must publish at least 24 times a year. Papers are expected to be a true alternative voice to the mainstream media in their communities. For most, it takes several tries. In fact, one AAN insider told Saltas that Private Eye had a “snowball’s chance in hell” of getting in when he applied. That’s all Saltas needed to hear: Private Eye was accepted on its first try in 1989, just three months later.

Once in the “club,” Saltas began learning the ins and outs of newspaper operations. He had one thing going that would prove to be the secret of the paper’s success: established ties to clubs, taverns and restaurants. “I’d never worked at any other newspaper before,” he says. “The first four or five years as a private-club newsletter were the perfect incubation period because I learned to do everything. It took a long time. Meanwhile, I was learning newspapering and building relationships with every club owner from Logan to St. George.”

During that time, private clubs weren’t allowed to advertise in newspapers, so no competition could develop. In 1988, when new Utah Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control rules were interpreted to allow clubs to advertise in the media, “I put the paper on the street instead of mailing it, and we immediately had an advertising base that no one was able to capture from us. That’s what got it going—what kept it going,” Saltas says.

The ‘Free’ in Freelancing

Saltas had already pulled together an impressive editorial team—freelancers and columnists such as John Harrington, Mary Dickson and Ron Yengich—and he’d rented an office in the heart of historic Midvale. Future editor Ben Fulton got his start freelancing for the paper during the Midvale days. Pay was minimal to nonexistent. Saltas would shuttle carless employees to and from the office, or on deadline days they might all work late and crash at the office.

Yet, the early days were a rush. “There was a certain sense of exhilaration not knowing if the railroad track leads over a cliff or not,” Saltas recalls. “And you had no brakes. People who’ve been on the edge know this. Some are frightened of it and some get exhilarated. And not knowing was a lot of fun, because we were just speeding and, man, what’s going to happen? We’re going faster, but it’s exhilarating. So, let’s do some more of it, make it go faster, even though it could wreck.”

One writer, Tom Walsh, stuck around long enough to become Saltas’ managing editor in 1992, and together they moved the paper’s offices downtown to 400 South, a few doors east of what was then Port O’ Call.

“Tom came from KSL broadcast news and had never been a print news editor,” Saltas says. “He really had to reinvent himself as a writer/editor. He set the tone for playing hardball. When Tom got you in his sights, he wanted to bite.”

“I had developed this admiration for the paper,” Packer says. “Having been a journalist in Utah, I appreciated the fact that the state really needs an independent voice maybe more than other states. The Tribune and the Deseret News were sort of joined at the hip through the Newspaper Agency Corporation. There really was not competition between the two papers and both of them were dodging what I thought were important stories.

“I also liked the fact that the paper appealed to the gay community. It wasn’t a gay newspaper, but it was a liberal newspaper that gave voice to gay issues, something that was sorely lacking in Utah, as well,” he says.

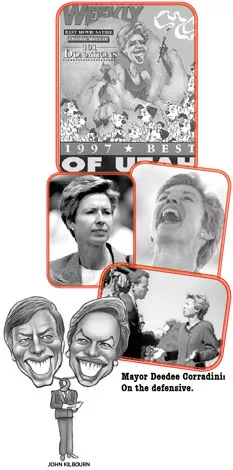

The Gift of Deedee

Packer wrote an investigative series on the Bonneville Pacific Corp. in the early ’90s, which looked at how former Salt Lake City Mayor Deedee Corradini and her one-time business partners funneled assets from bankrupt Bonneville Pacific, through offshore companies, to themselves.

“I used to tell my students at BYU: ‘No story is worth going to jail over, and that’s why you need to draw the line,’ ” Packer says. “But when I was working on the Bonneville Pacific story, there came a time where the line presented itself, and I took a chance and went over it. I was lucky.”

The Bonneville Pacific series led to an in-depth Packer investigation of “DeedeeGate” or “Giftgate,” where it was alleged Corradini used her office as mayor to solicit more than $231,000 in cash and loans to cover her debts in bankruptcy court.”

With such formidable muckraking skills, why didn’t Lynn Packer go to work as a reporter for Private Eye? “I was making far more money consulting. In fact, the money that I made consulting enabled me to do this. I considered what I did for City Weekly sort of like a duty. I enjoyed doing it, and I thought it was important to do. There were many other writers for City Weekly who had the same attitude—they weren’t writing for the money, they were writing because it was important that nobody else was telling stories like this. John Saltas had this gift to find them, to keep them happy—because it wasn’t with the pay—and keep it going. It was an enormous accomplishment on John’s part.”

The admiration would appear to go both ways. Of Packer’s journalistic chops, Saltas says, “Lynn Packer was a bull in a china shop. He’s so ethical, talented, professional—a great individual. Back then, we had an open turf. We had Packer’s stories for three or four years, untouched. That’s how pathetic the dailies were. They used to read our paper for scoops.”

Soul Mates & Soul Patches

Rocky Anderson, then a civil-rights attorney, now founder of High Road for Human Rights, was an early supporter of the paper. He and the paper “were soul mates in a lot of respects,” he says, “in terms of the values and the kind of changes that we saw that needed to be made, both in individual cases and more broadly in terms of public policy.”

Anderson immediately saw the promise of the fledgling paper: “I was thrilled that there was a truly independent source of investigative reporting in this community. It was a healthy thing, both in terms of getting better information and also providing a release valve for those who oftentimes were unhappy about abuses of power and the absence of people standing up to those abuses.”

Christopher Smart went on to edit Lynn Packer’s coverage of the Olympic bribery scandal and also, under his watch, the paper’s moniker became City Weekly. He nurtured freelancers like Andrea Moore Emmett, as well as Carolyn Campbell and Katherine Biele (both of whom still freelance for the paper). Smart, Saltas says, “brought a certain kind of fun to the office. He was connected. He loved reporting. He continued Tom’s legacy and elevated the style of City Weekly.”

When Smart left in 2002 to work for the Trib, alt-weekly vet John Yewell was hired to take City Weekly for what turned out to be a nine-month spin around the block. “John was a fine writer,” Saltas says of Yewell’s brief editor stint, “but hubris was his Achilles’ heel.” Yewell declined to comment for this issue. [Editor’s note: As if we weren’t in enough of a swamp attempting to report on ourselves, it should be noted that Yewell took a chance on current editor Jerre Wroble, hiring her in 2003 as copy editor, for which she is grateful.]

Ben Fulton stepped up for the next four years, capping off a long reporting career at City Weekly. From the calendar to music reviews to Fulton Files, Fulton had penned nearly every column in the paper at one time or another, although long-form features were his specialty. “Ben was our longest-tenured employee,” Saltas said. “He was a very crafty writer. He studied writing. In retrospect, he was miscast as an editor. I’m not surprised he’s chosen not to speak in this issue. Everybody here loved Ben and, sometimes, that affection was returned.” Fulton quit in 2007 and later went to work for the Trib.

Enter ebullient Holly Mullen, a Tribune exile, who, for two years, put her columnist muscle to work in her Mullen column as well as in newsroom blogs. “I really like Holly,” Saltas says, “but I think she’d agree the timing was not right” for her return to alt-weekly journalism (she’d previously written for alt-papers in Minnesota and Texas). Saltas was referring to the high political profile of Mullen’s husband and step-daughter, conflicts that can pose a reporting challenge for alt-journalists. Since leaving the paper, Mullen has announced her own candidacy for an at-large seat on Salt Lake County Council. She declined to comment for this story.

In 2009, Jerre Wroble got a chance to sit in the catbird seat with stern admonitions not to screw things up. [Editor’s note: As if … ]

Ground Control to Major Tom

There remains that nagging “mission” thing: Are the alt-industry, and City Weekly in particular, still on one? “We’re absolutely alternative and have never changed that stripe, by the definition of our industry, by the definition of what we do in this community,” Saltas insists.

“[The mission] seems to have been fairly consistent,” Anderson says. “There were things I didn’t really like seeing in City Weekly when I was mayor because I think it was personally motivated. [John Saltas] and I had earlier been friends, and there was a blowup there. But, I have always really valued the role that City Weekly plays in providing information and a different perspective that wouldn’t be present in our community. I see it as sort of the journalistic equivalent to the role that Saturday’s Voyeur plays in part of our cultural community.”

Echoing Anderson’s sentiments is lobbyist, former state representative and Deseret News columnist Frank Pignanelli, who wrote in an e-mail, “Although the Weekly can be hard—and sometimes unfairly—on those with whom the editors disagree, our community needs an alternative voice.”

That voice is curiously of interest to all ears, not just those of the liberal persuasion. “It became clear that the readership cut across a fairly wide swath,” Packer says. “There were, you know, Republicans, Democrats, Mormons, non-Mormons—just a lot of people who valued multiple viewpoints. I was really surprised how many Republicans read the papers and gave me feedback on the pieces I wrote.”

David Carr, a former alt-weekly editor and now a media and culture columnist for The New York Times, applauds the broad-based appeal of the alternative press. “On the one hand,” he writes in an e-mail, “alternative papers had it absolutely right: high quality editorial freely distributed, with ads sold against the audience. Sounds downright modern right now.”

Going forward, though, Carr fears alt-weeklies have their work cut out for them: Like many newspapers, he says, “alternative weeklies have a lot of content on hand, a great ability to manufacture more, but not the best history of organizing that information. Although many alt-weeklies were alert to the perils and possibilities of the Web, many had execution problems along the way and lost what had been a big advantage heading into a consumer Web age.

“In a sense,” he says, “the threat was too large and too secular to escape: Alt-weeklies were ad hoc tribes of like-minded folks who pivoted around specific interests—city politics, music, sex, theater—and the Web allowed those folks to organize without a media property in the middle or a digital maypole. Getting a nascent generation of consumers to organize around a printed product is going to be pretty tough.”

Minding Our Mantra

Carr, who met Saltas through AAN and has visited Salt Lake City on numerous occasions, is impressed by the paper’s loyal following: “Every time I get to Salt Lake, I am stunned by the continuing level of commercial and civic engagement with the paper. It’s weathered very complicated times with a great deal more alacrity than its peers. I could blame it on the leadership and vision of John Saltas, but then he would just get a big head, so let’s speculate that the existence of a dominant and occasionally oppressive culture has created a strong affiliation among people not associated with the culture. City Weekly’s steady focus on creating accountability from and in a city through hard-hitting political coverage leaves many of the citizens feeling that the paper is looking after their interests.”

Despite the dire prognostications for print media, Packer thinks City Weekly is in better shape than most to continue hard-hitting investigative work. “City Weekly is uniquely positioned for investigative reporting,” Packer says, “because it doesn’t have deep pockets. You have this little City Weekly that isn’t litigation proof—you can sue ’em and put ’em out of business, but you’re not gonna get rich doing it.

“But the other thing that John Saltas has is high standards—for most of the stories I did, he had Rocky Anderson go over them with a fine-toothed comb, and that’s the responsible thing to do.”

Packer sees an evil triumvirate of technology, deregulation and the recession conspiring to further fracture media audiences to the point that the money needed to pay the cost of reporters and their investigations will disappear. “Eventually,” Packer says, “a new way of reporting, a new way of professionally gathering information, needs to emerge. But I don’t think anybody knows how that’s going to happen and, really, if it’s going to happen. Just as other institutions are in decline in the United States, our journalistic institutions are in decline and may continue in sort of a free fall, and the United States may never regain its position as a world leader. It’s interesting what’s going on right now.”

Saltas concedes that while the past few years have been tough on newspapers, “We’re moving more papers from our racks than ever, so folks can stop the ‘newspapers are dead’ routine. They’re not. If the Tribune wants to die, let it die, but we’re not dying. Between the Internet and mobile and social media, we have channels everywhere and people can find us in more places than ever.”

In late 2003, Saltas managed to replace himself as publisher with Jim Rizzi—a 20-year New Times (now Village Voice Media) executive who worked for alt-papers in Los Angeles, Denver, San Francisco and Phoenix. The move has enabled Saltas to dedicate his time to new ventures like developing publishing software and products through his affiliated companies AveNews.com and Kostizi.com.

Saltas takes considerable pleasure in the successes of former employees. Tom Walsh, for example, left in 1996 to edit the Miami New Times and now is editor of the San Francisco Weekly. “Tom had ambitions to get good at a new career, and he did it successfully and has moved on. You gotta give him credit for that,” Saltas says. Former writer Shane McCammon is an Air Force JAG attorney. Former production manager Kat Topaz designs papers and Websites throughout the alt-industry.

“We’ll continue to entertain, enlighten, educate, and we’ll always be smartasses,” Saltas says. “We won’t kowtow to anyone. That’s my mantra. It’s been that way forever. If I have to take lumps, I’ll take them, but I’m not going to bend over for anyone.”