Page 2 of 3

THE FEAR FACTOR

After court, Tarin meets with Comunidades Unidas’ Morales, who wants attorney to join the nonprofit’s board.

Over lunch in a nearby food hall, they discuss SB81, a bill sponsored by former Sen. Bill Hickman, R-St. George, that sought to make it harder for undocumented immigrants to work and live in Utah. Rep. Mike Noel, R-Kanab, the House sponsor of SB81, says even after the bill became law, he remained concerned about a number of lingering issues. Those include the cost of treating undocumented workers in hospitals and identity theft. But he also worries about the undocumented workers being unable to report employers who treat them unfairly. He doesn’t want to be the “poster child” for the anti-immigration groups.

Sen. Luz Robles, D-Salt Lake City, condemns SB81 as sending a message that Utah is not a welcoming state. If the intent was to create fear in the undocumented community, she says, “then it was fulfilled.”

Tarin agrees. “The biggest damage SB81 has done is it’s sent out a message: Don’t trust anyone in law enforcement.” He cites a Hispanic woman and her daughter asking for advice on breaking their contract with a landlord.

The mother suspected he was sexually abusing one of her other daughters, so Tarin told her to report him to the police. She refused. “They’ll deport me,” she said. “I just want him to let us leave.”

Tarin and Morales agree that for those who hold antiimmigrant views, SB81 gives them a license to put them into practice. “People feel justified in indulging their xenophobic tendencies,” Tarin says.

He accepts Morales’ invitation to join her board, while warning her he is controversial. “I go after notarios [notary publics] and attorneys who do shady stuff.” Some notarios, Tarin says, work as quasi-lawyers, filling out immigration forms for undocumented clients, the result of which is often that immigration officials become aware of the individuals and deport them.

He first started hearing stories of malpractice when he volunteered at the Guadalupe School Pro Se Legal Clinic as a law student. He heard horror stories from immigrants “of unscrupulous notarios and attorneys charging them for doing nothing, filing cases that end up in deportations, gross abuses of attorney relationships.”

Tarin is not the only immigration attorney who has tried to tackle malpractice. But in a community of lawyers that arguably prefers to wash its dirty laundry in-house, he sees the media as “a necessary evil” to push for change.

At the end of 2008, 15 Hispanic LDS families who were facing deportation proceedings came to Tarin. They claimed a notary called Leticia Avila, herself LDS, had conned them out of thousands of dollars with false promises of legal status. An Anglo missionary couple convinced them to denounce her to the authorities. But after several years, Avila remained free and her alleged victims faced deportation.

Tarin was infuriated. “Taking advantage of those people’s religious beliefs to defraud them made it so I couldn’t stay quiet any longer. I couldn’t believe no one was doing anything about it.”

In April 2009, City Weekly broke the story in “Money for Nothing.” Avila admitted in an interview to taking money from undocumented Hispanics, supposedly to help them get their papers. Subsequently, the Utah State Bar sued Avila.

Avila, in turn, countersued Tarin and numerous undocumented Hispanics who alleged she scammed them, although Tarin says that, as of yet, nobody has been served. Avila’s attorney, Steven Paul, declined to comment on either lawsuit.

“It’s a typical effort to intimidate victims and use their fear of being deported against them,” Tarin says.

One victim, 60-year-old Tomas Flores, recently testified against Avila on behalf of the Utah State Bar. Flores says he and four family members paid her several thousand dollars to resolve their undocumented status. All they got in return were empty promises. Attorney Paul says, “we are aware of his accusations, and deny them emphatically.”

Only one of Flores’ four children still remains in Utah, the other three and their families already deported to Uruguay. “It’s going very badly for them there,” he says.

Avila, Flores says, with her claims to be inspired by heavenly visions and her LDS connections, tricked them. “Who comes into your house as a thief and offers you everything you want?”

QUEEN OF THE AMERICAS

On

July 29, 2009, federal prosecutors indicted immigration attorney James

Alcala over allegedly arranging thousands of fraudulent visas for

undocumented Hispanics to work for Utah companies. Earlier this year,

attorneys Lance Starr, who worked for Alcala for nine months, and Sean

Foster, both friends of Tarin, persuaded numerous clients who claimed

Alcala had cheated them to testify against Alcala to the U.S. Attorney.

Alcala says Starr “betrayed me.” The case is currently in federal

court, and a hearing was scheduled for Jan. 7.

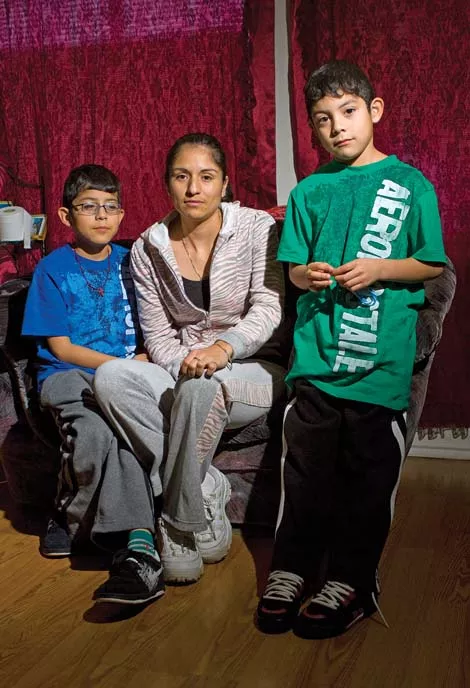

Alfaro lives in a Glendale house with her two young sons.

The mantelpiece is a shrine to the Virgin of Guadalupe. “She is the mother of God, the queen of America,” Alfaro says in Spanish. “She has been a source of hope to keep me going.”

Legal resident Alfaro married undocumented roofer Leonel Medina on Dec. 17, 1999. In September 2007, Medina went to Alcala’s firm for help becoming legal. Alcala told Medina to come to the federal immigration offices in Salt Lake City on April 30, 2008, and bring his family. He went in with Medina while Alfaro and the boys waited outside. Alcala, who describes the Medina case as “an albatross around my neck,” says immigration officials pressured Medina to admit he had been caught entering the United States with fake documents. It was only then, Alcala claims, that he learned Medina had been deported previously. Medina was arrested and deported to Mexico the following day.

Alfaro, however, says her husband told Alcala he had been deported once, only to illegally return to the United States, and gave the lawyer copies of his deportation papers. At that point, Tarin says, Alcala should have known there was nothing to be done. Having been deported three years before and illegally returned, if Medina went to immigration, he would be immediately removed from U.S. soil.

The case didn’t end with Medina’s deportation. Alfaro denounced Alcala on a Utah Hispanic TV news show, accusing him of asking for an additional $5,000 to bring Medina back, and she wrote in a 2008 complaint to the Utah State Bar that Alcala knows “this is impossible.”

Alcala, however, says he told Alfaro he might be able to get her husband back for $5,000, but she went to another lawyer before he could investigate further.

Tarin says that such offers of help were “clearly frivolous. It was a ploy to get more money out of a suffering victim.”

After a meeting with the Utah State Bar over Alfaro’s complaint, Alcala gave her back $2,800 in fees and, in April of this year, successfully secured her citizenship. Alcala continues to practice law, albeit with an ankle monitor, and says that despite the federal allegations, clients continue to seek his help because they know he will fight for them.

But the citizenship and refunded fees bring little comfort to Alfaro, who is constantly struggling to make ends meet and particularly since her children have struggled with the loss of their father. “If I kill myself, will immigration bring papi back?” one of her sons asked her.

BEER WITH A METH CHASER

For

about 50 percent of Tarin’s potential clients, he says, “the best

advice is do nothing.” But when Tarin says he can’t help, he knows many

will go to lawyers or notaries who will take their money, give them

empty promises, or at worst, get them deported.

That leaves the bulk of Tarin’s practice defending aliens in deportation proceedings, such as Efren Robles (no relation to Luz Robles), transferred in August from a California court. The West Coast is overwhelmed by deportation proceedings, Tarin says. Clients like Efren Robles, with a considerable criminal background, inevitably test his faith. “It’s frustrating to see immigrants who have been at the gates of opportunity, had the American dream for their taking, and to a certain degree squander that opportunity.”

Chained and manacled, Efren Robles shuffles into courtroom two and sits next to Tarin before prosecutorturned-immigration judge, Dustin Pead.

Tarin goes through Efren Robles’ lengthy rap sheet of 11 Californian convictions, including four DUIs and one for meth possession, in 2003. While Efren Robles, speaking through a court translator, offers sometimes confusing testimony, he constantly repeats his regret over the crimes he had committed.

Following an August 2006 DUI conviction, Efren Robles went to a rehabilitation home called Victory Outreach in San Francisco. He left 18 months later and, he tells Pead, has not drunk alcohol or done drugs since. In October 2008, however, he was sentenced to 90 days for a probation violation, after being picked up by police with a man in possession of a crack pipe. Efren Robles hired a lawyer who got drug possession charges against him dropped. Efren Robles denies to Pead having consumed alcohol or drugs since Victory Outreach, although a urine analysis report showed positive.

Tarin’s first character witness, Victory Outreach’s Pastor Richard Prieto, says in a telephone call from San Francisco that Efren Robles underwent genuine change in rehabilitation. Pead abruptly summons Tarin and the prosecutor to his chambers. He tells Tarin that Efren Robles’ fate comes down to whether in 2008 he relapsed into drug use or not. He will schedule more time for the case in February so the lawyer can gather more evidence.

“You can put him in a better position,” Pead tells Tarin. “I am uniquely obligated to make the best judgment I can.” The case is continued to Feb. 10.