The day I’ve long awaited and long predicted may have arrived: Comic books are being taken seriously as cinema and as drama. But this day hasn’t arrived out of nowhere. It’s been building for the last decade.

The first major film drawn from comics was 1978’s Superman, which came along at just the right time to catch the blockbuster wave that was sweeping Hollywood: Jaws and especially Star Wars had demonstrated that audiences would respond—outrageously so—to pulpy genre fiction up on the big screen. But all through the ’80s, while the blockbuster film flourished, comic-book adaptations did not. Even the Superman films finally sputtered and descended into self-parody.

The 1990s saw some experimentation with the comic-book movie. The Rocketeer (1991) was a pale imitation of the Superman approach, and while it’s watchable and vaguely amusing, it’s nothing extraordinary. Jim Carrey’s 1994 film The Mask—yes, it’s based on a comic book—took chances and paid off at the box office, but it’s hardly anything that can be considered dramatically or cinematically important. Ditto Men in Black (1997) and Mystery Men (1999), both of which sent up genre fiction and are still enduring favorites with fans, but aren’t anything you’d send your mom to see.

Then things started getting serious with 2001’s Ghost World, based on the graphic novel by Daniel Clowes. It’s one of the best stories of disaffected adolescence I’ve ever seen—and it’s about girls, to boot! Then came 2003’s American Splendor, a biopic of cult comic-book writer and professional malcontent Harvey Pekar based on his own underground comics about the mundanity of his life. Both films received Oscar nominations for Best Adapted Screenplay, and both won a slew of notices from film festivals and critics groups. But that’s not why they indicate a turn toward importance for the comic-book movie. It’s because the movies were finally noticing what comic books had been doing for years: moving beyond the standard caped-crime-fighter story to use the medium to explore other matters.

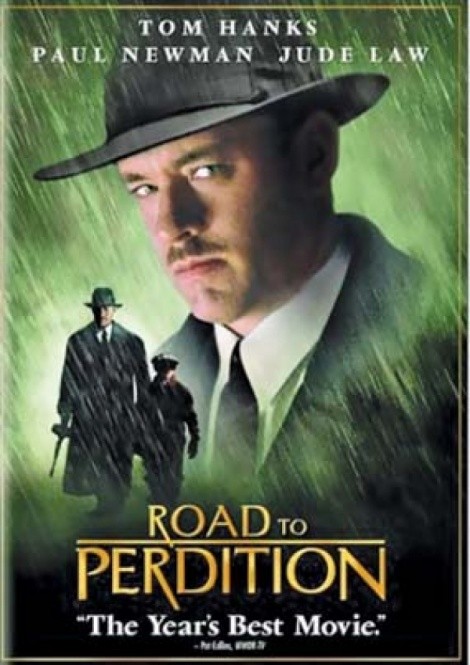

Comics also started to question the presumed morality of crime and punishment that earlier stories in the genre had taken for granted. Road to Perdition (2002)—based on the graphic novel by Max Allan Collins and Richard Piers Rayner—received multiple Oscar nominations for its tale of a Depression-era mob hitman and his collision with the upside-down morality of his chosen profession. The thematically similar A History of Violence (2005)—from John Wagner and Vince Locke’s graphic novel about a former mob hitman trying to escape his past—received an Oscar nomination for Adapted Screenplay and lots of love from critics’ groups for its performances, including Viggo Mortensen’s lead and the supporting work of Maria Bello and William Hurt (the latter of whom was also nominated for an Oscar, perhaps presaging Ledger’s nomination and win).

Not every comic-book movie of the 2000s has deviated so radically from the expected. Ang Lee’s 2003 Hulk was more arthouse than action, but it still told a standard superhero story. The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, from that same year, couldn’t even manage to tell a standard tale with any coherence. But films like those are being forgetten in the wake of stunning work such as 2005’s Sin City and 2006’s V for Vendetta and 300, which draw on the vivid and striking imagery of still drawings to imbue cinema with a unique visual freshness, and draw on the cultural revisionism of the stereotypes and archetypes graphic novels today upend for unexpected depth. And with the vitality and the creative wealth of medium, we surely have many years and many movies to go before Hollywood taps out the comic book.