Buzz Blog

As

most film companies have now boiled their special effects down to

whatever they can force out of a computer, for a long time 90% of

those effects were created by designers for physical creations.

Ten years ago films like “Avatar” or “Transformers” would

have had to hire teams to create the costumes and build the

outlandish, with computerized graphics playing only a minor role in

the overall process. A skill that has been whittled away with every new piece of tech. Which is why people recognize the cinematic

craft for the true artform it is, helping define many of the sci-fi

and action films we grew up with and , that defined the term “movie

magic”

--- Local

artist Ryan K. Petersen was one of those magicians for a number of

years, having a hand in the design of characters and props from films

such as “Mortal Kombat”, “Men In Black” and “The Devil's

Advocate” to name a few. Now only working on film materials

part-time, he's taken up residence at Poor Yorick Studios to continue

his design artwork and sculpting, including creating The Brothers Bighead exhibition

you can check out next week up at the Art Barn on Finch Lane, and other works you can check out in a couple weeks at Poor Yorick Studio's open house on the 25th and 26th. I got a

chance to chat with Ryan about his career and works, plus his

thoughts on local art and a few extra topics.

Ryan

K. Peterson

http://www.ryankpeterson.com/

Gavin:

Hey Ryan! First thing, tell us a bit about yourself.

Ryan:

Well, I began my life in a sparsely populated, northern Utah town, surrounded by more cows than people, where I was raised in a very

loving, open-minded household. I’m now forty years-old and attempting

to live a comprehending and creative life.

Gavin:

What first sparked your interest in art and what were some early

inspirations for you?

Ryan:

Dinosaurs were the first to seize my imagination. It happened when

I was, oh, probably the age of three or four. They were an obsession. I

had dinosaur toys, dinosaur decorated plates, bathed in dinosaur

bubble baths (with a memorable plastic, Brontosaurus container),

dreamt of going to Dinosaur National Monument, and read every book on

them I could get my hands on. Eventually, it simply wasn’t enough

to consume all of this Dino stuff and I had to draw and sculpt them.

Then movies expanded my obsessions. My parents, mainly my father,

took me to see a lot of movies while growing up. I saw "2001 – A

Space Odyssey", "King Kong" the 1976 version, "The Island Of Dr. Moreau" "White Buffalo" and "The Land That Time Forgot" to name just a few that

had impact. But the most memorable was seeing "Jaws" when I was five years

old. I remember that day in vivid detail: I went to the bookmobile

with my sister, checked out a few dinosaur books and walked home on

the moody, cloudy day in anticipation for a movie I wasn’t prepared

to see. In fact, I barely saw it. After the scene where the boy on

the raft was eaten I buried my face in my dad’s chest and just

listened. Soon after, I had to cover my ears for total sensory

depravation. An interesting note: Because of "Jaws", I still dream

monthly about sharks. They’re never about me being attacked just

weird scenarios with sharks in them. Now, lest one reading this

becomes a bit too judgmental toward my parents for letting their

young son see such films, just know I wouldn’t have changed any of

it. I owe my active imagination to those early experiences.

Ryan: So

after Dinosaurs, I grew to add monsters, giant gorillas and sharks to

my creative repertoire. Around the age of ten, I started to idolize

those who made monsters for a living - guys like Ray Harryhausen,

Dick Smith and Rick Baker. A little later, in my teens, I became

fascinated by film directing and two directors in particular, Stanley

Kubrick and David Lynch. Because of them, I started to trust my

analytical skills – I felt like I “got” what they were doing.

When I would watch "A Clockwork Orange or "Blue Velvet", both Kubrick

and Lynch played with the principles of music, visuals and sound in a

way that made me high – not a literal high, but something related,

like a natural, aesthetic rush. To me it was one of the best

feelings in the world. If the process of movie directing didn’t

seem so exhaustive I think I would be doing that just so I could get

closer to the source of “the high” that I love so much. With the

exception of art classes and sports, I didn’t engage much with High

School. My mind was elsewhere – it was awakening to the power of

cinematic creativity and the need understand it.

Gavin:

You got your BFA from the U in Fine Arts. What made you choose the U

and what was their program like for you?

Ryan:

During my search for which University to attend, my parents and I

took a tour through the University of Utah’s art department. Two

things swayed me there. The first was seeing pink blossom laden

trees outside the ceramic department’s windows and envisioning how

wonderful it would be to create in such a room where they were

visible. The second occurred while on the third floor in the

painting department. We were taking in the vibe of the place –

looking at student work on display and peering into classrooms - when

the elevator binged and its doors opened up. Instead of seeing

students or teachers exiting, out walked a German Shepherd. He was

the only one in the elevator and proceeded to casually head down the

hall with not a care in the world. Our guide told us the dog

belonged to one of the painting instructors, and was a regular

presence within the department. It was such a wonderful moment that

it sealed my decision. I was going to the U. The irony of my choice

was that I had planned on majoring in sculpting and within my first

year two key sculpting instructors left and the department fell into

disarray. I took the painting and drawing track instead. This

proved to be fortuitous because Dave Dornan, Sam Wilson, Paul Davis,

Maureen O’Hara Ure and Tony Smith were excellent instructors and

very interesting people to boot. I graduated in 1993 and am so

grateful to have been a student during that time.

Gavin:

What really pushed you toward sculpture and design work as your main

craft?

Ryan:

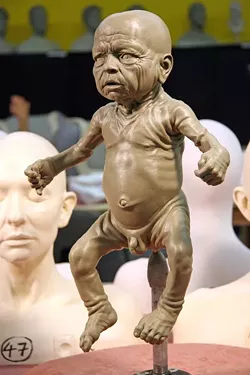

I have two different creative “hats” that I alternate wearing.

One hat, my “monster hat,” represents my youthful passion for the

fantastical and was spurred on by my monster making idols. I wanted

to have skills like them so I practiced sculpting pretty much every

day (I had good discipline). This hat is what I wear to make a

living as a sculptor/designer for film, animation and gaming. It’s

mainly technique driven and requires very little critical thought.

The second hat is my “fine art hat.” It formed in college and

reflects the more adult side of me satisfying my intellectual,

aesthetic and emotional needs. Both hats keep my awareness in check

so I don’t become too discouraged with the difficulties of living

life. As for your question, I’ve been strongest in, and had the

most patience with, sculpture. Drawing has become increasingly

frustrating for me. In fact, I don’t draw anymore. If I do, I do

it in the computer because it’s more forgiving. Now painting is

different. Going to the University of Utah, and learning from such

great painters, instilled an appreciation for painting. I guess I

feel less restricted while sculpting and painting let’s me play

with color, mood and composition. Unfortunately, ego is a director

too. If you don’t enjoy doing something you won’t improve and

you won’t get praise. So much of what guides artists, and I

suspect humanity in general, is to go where one’s ego gets fed.

Personally, I wish I could rise above this. I would like to be more

explorative with my art technique but my ego wants me to play it

safe. I’m gradually changing this. One of the benefits of getting

older is that I don’t care so much what people think.

Gavin:

How did you first get involved working for film studios as a

designer?

Ryan:

I don’t work directly with the big studios like Universal, Disney

or Sony studios. In the past they had their own special effects

facilities but that changed I think in the '70s and '80s. Now

special effects and make-up companies are independent of the studios

and compete with each other for gigs. These various companies,

usually started by talented artists who had to expand in order to

accommodate the scale of special effects required, hire people like

me for help. For instance, Rick Baker, who is a seven time Oscar winner and just won for "The Wolfman", is so talented he could do every aspect

of a special make-up effect himself but can’t, most of the time,

due to time restraints. He needs a crew of specialists – mold

makers, painters, sculptors, mechanics, hair ventilators, etc., which

can vary from a handful to, on the big projects like "Men In Black",

close to a hundred employees. Anyway, after college, I made various

portfolio packets – photos, cover letter, resume - and sent them

out to special effects companies I admired. I sold myself as a

sculptor. Not until I got out to L.A. did I realize how important

2D designers were to the process. I just assumed sculptors did much

of the designing, since that is what Rick Baker did. I considered

myself a designer, one who designs using clay, but didn’t always

get a chance to do so. That has changed with the introduction of 3D modeling programs like Zbrush. In a way, sculptors now have an

advantage over 2D designers because they can quickly realize a

character dimensionally, light it and render it, providing more

visual information than previously accustomed. Technology has an

interesting way of reversing fortunes in this business; we’ve all

felt the sting of it in one form or another.

Gavin:

What was your first big motion picture you worked on and what was

that gig like?

Ryan:

I was first hired in 1994 by a relatively new company called

Amalgamated Dynamics Inc. (A.D.I.). It was founded by a couple of

talented guys, Alec Gillis and Tom Woodruff Jr., who had worked for

Stan Winston of "Jurassic Park" fame. They were about to start "Mortal Kombat" and needed some sculptors to flesh out the four-armed

character named Goro. I drove out to L.A., got a hotel room

and worked on the film for five weeks. It was awkward at first. I

didn’t have any of the right tools and had to adjust to the high

quality of sculpting that surrounded me. It was sink or swim time.

Luckily, after the job, Tom and Alec asked me to stick around. "Mortal Kombat" soon led to "Jumanji" and I was officially living my

childhood dream. I’m very grateful to Tom and Alec for giving me

my start.

Gavin:

You've worked with a number of different companies, Cinovation and

A.D.I. to name a couple. What is it like for you

switching between them and working with different designers?

Ryan:

Some shops owners are legends within the film industry. They’re

respected so they get the bigger budgeted films with the longer

schedules. This is changing rapidly due to the technological shift

from practical effects to digital. To work under those conditions

can be fun - real quality can be achieved and that’s what it’s

all about. The down side is the crews are larger and more

departmentalized. When working for smaller shops you may get to do

more, and with less restrictions, but you have to work fast, which is

not always conducive to creating quality work. I think the one

project I worked on that was a nice combination of both was "The Curious Case Of Benjamin Button", for which my boss, Greg Cannom, won the Oscar

for best make-up. I had time and freedom on that one. What I miss most, when not in L.A., is working for,

and with, truly gifted people. Rick Baker ("Star Wars", "An American Werewolf In London" and "Harry & The Hendersons") and Rob Bottin ("The Thing", "Robocop" and "Legend") for example are geniuses. I say that without

the slightest hesitation. It’s not often one gets the opportunity

to work for brilliant people. It’s incredibly stimulating. What’s

sad is that these guys are slowing down. Rick is more selective

about work now and Rob Bottin hasn’t done anything for eight years (I

have no idea why this is). The younger filmmakers coming up in

Hollywood have different influences and may not even grasp what these

men can do. It has made me aware that, when time passes, it’s not

a given that progress is being made. Things just change they don’t

necessarily improve.

Gavin:

For those interested, what are some of your prominent designs we've

seen in movies?

Ryan:

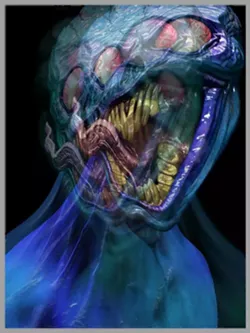

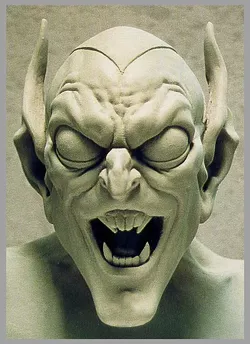

Most of my work has been collaborative so I can’t take sole credit

for much of it. The stuff that I think reflects my aesthetic

sensibility the best are the Edgar character in "Men In Black" and the demons in "The Devil's Advocate". Many of my designs throughout

the years never made it to screen. The Green Goblin for "Spider-Man" was one of them. It went out the window when the

production opted for a static mask instead of a make-up. But, I must

say, the work I lament the loss of most are the designs I did for Rob

Bottin’s directorial debut. The movie never happened but I am very

proud of the stuff we came up with. Unfortunately, I don’t have

any photos. It’s a weird feeling knowing your best work will never

be seen.

Gavin:

You also dabbled in computer graphics for video gaming for a while.

What persuaded you into exploring that field and what was it

like?

Ryan:

In 1999, a year after moving back to Salt Lake City, I was hired by

a local gaming company, Beyond Games, to provide clay character

sculptures with the understanding that I would also be introduced to

digital modeling. Just prior to that I had worked on "The Grinch" for

Rick Baker (I no longer lived out there so I stayed on the couches of

friends for a few months), and one of my co-workers, Aaron Sims, was

getting heavy into digital work. He was one of the first practical

artists out there to do so and was very effective at it. Anyway,

Aaron planted the seed so when the opportunity came to get my feet

wet digitally, I took it. My practical work at Beyond Games did

eventually segue into learning 3D modeling programs like Maya. It

wasn’t easy. I was a computer illiterate and the left parts of my

brain being forced awake protested. Also, Zbrush, a very effective

sculpting program, had not been released yet, which would have made

the adjustment easier. Kris Johnson and Clark Stacey, Beyond Games’

President and Vice President (who have since started Smartbomb Interactive) were very patient with my rather

sluggish learning curve. All in all, it was a valuable

experience.

Gavin:

After a number of years it seems you pulled back from doing design

work for films. What brought on that decision?

Ryan:

That was due to me living in Utah. I moved back so I could start

creating fine art. I knew I needed a break from L.A. when I kept

returning to this book I had on the English painter Francis Bacon. I

was enamored by a particular photo of him working in his studio. For

those not privy to Bacon, his painting studio epitomized creative

chaos – the domain of a hoarder aesthetician. I guess I was sick

of doing work for others so to me his studio and life represented

unabashed, creative freedom. I wanted that. So I moved back

home.

Gavin:

When did you first come across Poor Yorick Studios, and what made

you decide to move in?

Ryan:

I had to have a studio if I was to take this turn in my life

seriously. So I checked out a building that advertised art studios

for rent. That’s when I met Brad Slaugh. I recognized Brad from

the University of Utah’s art program and seeing him was reassuring

because I’d rather rent from a fellow artist. Now, this was back

in 1998 and I don’t think Brad had been in the business of studio

rentals for long. The building he was sectioning studios out of was

located on 3rd West and 4th North and had yet to be called Poor

Yorick studios. It turned out to be exactly what I needed and I’ve

rented from Brad ever since.

Gavin:

What's the process like for you when creating an original piece,

from concept to finished product?

Ryan:

It starts with an idea. Sometimes the idea initially communicates

itself as a whisper - a hint of something worth creating. At other

times, the idea presents itself loud and clear, which can be a

blessing or a curse depending on one’s energy level (It’s easier

to ignore the whispers). There’s a flip side to all of this and

that is that some ideas are dead end duds. That is why it’s so

critical for an artist to hone his/her intuition, especially if you

work with expensive materials like I do. Now, some artists are more

technique oriented and less concept driven. I respect that. At

times, I enjoy looking at a good landscape painting as much as

processing somebody’s abstract idea. I understand the need to

create both. So, if I get excited about an idea, and feel it’s

worth committing to, I will start by assembling the materials to

create it. Once I’ve begun my main fear is to not finish it. If

that happens, it can be pricey and a bit deflating emotionally. I

consider my artwork complete when I lose energy, or realize the idea

has stopped communicating, or reach the point in my mind’s eye

where I envisioned it finished. Most of the time, it’s a

combination of the three.

Gavin:

Do you usually play around with the concept before finishing it, or

are you pretty determined to keep what you had in mind as the final

look?

Ryan:

If the concept is hazy, or still a whisper, I will “play” with

it. A while back I had an idea to go to Deseret Industries and find

a cheap, cool looking frame that I could sculpt a clown face in, sort

of a relief piece. Not the most original or interesting start, yet

for some reason I felt it was worth continuing. I ended up with

various small picture frames from the D.I. and just started

envisioning how a sculpted face might play within each of them. I

usually like to explore ideas as a series to fully exhaust their

potential. So the plan became to mold my favorite of the frames and

cast multiple copies of it so I could explore various clown faces in

each… Frame... Clown… Sculpted frame… Utah shaped frame…

Utah state Senator Chris Buttars… Buttars as a clown… Buttars

as a puppet… Buttars spewing vomit... And so it goes. That’s

how my “Public Forms” series on Chris Buttars came about. I don’t

make a point of attacking people I disagree with. I believe in

diverse points of view. But when people in power keep delivering

hate speech I feel compelled to react the best way I know how. I’m

sure Mr. Buttars has a good side, but man, the guy is sure resistant

to show it.

Gavin:

Considering the kind of work that you do, what's the difference for

you in creating something by request and coming up with something of

your own?

Ryan:

If I’m wearing my “monster making hat” I can sculpt or design

upon request. That is, technique can be a compelling enough reason

to move forward – a challenge, say, to sculpt the coolest wrinkles,

forms or bone structure possible. It’s not as easy to do this

while wearing my “fine art hat.” If I had to create someone

else’s idea, or suggestion for a piece, it would kill my creative

energy and betray my process. I will never say never; especially if

a lot of money is involved, but it would feel… Faustian.

Gavin:

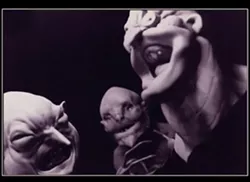

Currently you have The Brothers Bighead on exhibitionup at the Art Barn. Where did the

idea come from in creating them, and what was it like putting them

together?

Ryan:

I’ve always loved dioramas. It goes back to my love of Dinosaurs

and seeing them featured in various dioramas in Museums. My idea was

to create four different dioramas each contained within a sculpted

shell. I wanted to make sure the outer sculpture was interesting

enough to hold a viewers attention. That way when the viewer figured

out they housed interior sculptures it would be a bonus to their

experience. Once I had this concept down I knew it was going to be a

challenge creating them. Goodness, they were expensive, time

consuming and required the use of toxic materials. Worst of all, I

knew I had to make them because I loved the idea so much. Once I had

a rough idea of what the outer shells were going to look like I

sculpted them. They were big sculptures so I wanted the finished

molds to be made of a light weight material. I made them out of

silicone and fiberglass resin at my Poor Yorick studio. That was a

mistake. The resin used is toxic and I tried to contain the smell of

the resin by blocking all the openings from my studio to the rest of

the building. It didn’t work. I subjected my fellow artists to

this horrible material and it was irresponsible. I now had to

continue the process somewhere else. I ended up casting all the

polyester resin outer shells, from their molds, in my parent’s

barn. It took forever because I tackled each stage, of what was

going to be a series of four pieces, simultaneously. Everything had

to be done in quadruplet. That way, if a subsequent stage proved too

difficult, I wouldn’t be discouraged from plowing ahead on the

other three. After completing the outer shells I had to narrow down

what would be inside the heads – what the dioramic subject matter

would be. This too was hard and their engineering was a nightmare.

The internal scenes required miniature sculpting, wiring, soldering,

LED lights, vacuum form plastic, more fiberglass… oh good hell, it

was never ending. On and off, the Brothers Bighead series took five years to complete. And I wouldn’t have changed a thing because the

idea was so satisfying to explore.

Gavin:

Are you looking to do any more grand exhibitions over the rest of

the year or adding onto this one?

Ryan:

No, not really. To be honest, I’ve had to delve deeper into

digital sculpting to expand my skill set because I went a long time

without employment. I used the down time to learn Zbrush because my

digital education had stopped six years earlier with gaming and the

program Maya. Zbrush, by the way, is an amazing computer program.

It was designed with practical special effects sculptors, like me, in

mind so we could do the things we were accustomed to doing in

Hollywood. It came out after I had left gaming and it became a

revolutionary tool for the entertainment industry. Young people were

doing some amazing stuff that was becoming too difficult to ignore.

And once "Avatar" came out, it became painfully obvious that practical

special make-up effects and animatronics were in trouble. Digital

creations were the future, whether I liked it or not, so I had to

adapt. The consequence of this, and there are always consequences,

is that I haven’t put on my “fine art hat” for quite some time.

I feel out of balance and a bit empty. I’m not complaining. I

know with every door that shuts, another opens. I’m just orienting

myself to the reality of this new room.

Gavin:

Going local for a bit, what are your thoughts on our art scene, both

good and bad?

Ryan:

Our local scene has genuine, strong voices. I’m so impressed with

what I’ve seen. Unfortunately, living away from the coasts, we sit

in relative isolation from the nourishment an appreciative audience

provides. For instance, my artist friends in L.A. are doing very

well. We, by contrast, seem to be lone voices in the wilderness. I

guess I shouldn’t speak for others. I just know I haven’t

figured out how to survive yet. I was watching a documentary on Bob

Dylan and one of the people interviewed talked about how in the 60’s,

artists, even the citizenry, were valued for “what they had to

say.” He went on to say it’s different now – priorities have

changed. I agree. The Utah artists who actually have something to

say are the counter culture providing balance, albeit small, to our

community. The best of us are the release valves, the voices of

conscience, the annoying itch to collective, psychological decadence

and a challenge to the status quo. It’s a struggle to live this

way: It takes time, resources, attention, sacrifice and energy.

Most people I suspect are too distracted to care these days - there’s

just too much stimuli out there. That’s why I create art to please

myself and if others like it, well, all the better. That’s why I’m

so grateful for my Poor Yorick studio. Twice a year we open up our

doors to the public and get to display our work to those who seem to

care.

Gavin:

Is there anything you believe could be done to make it more

prominent?

Ryan:

There are pretentious and rather asinine ways to achieve prominence

these days, especially in the art world. Anyone who has seen the

documentary "Exit Through The Gift Shop" can attest to that. So maybe

we should consider whether prominence would actually improve our

scene. If say, a particular artist’s voice is loud enough to reach

areas that give a damn, what would the consequences be? Would it

stimulate others to find their own voice or motivate mimicry? For

every original voice, there is an army of emulators. This can garble

communication. At the same time, artists need to keep expressing

themselves. If they can’t because their invisibility has taken a

financial toll, well, that’s a problem. I guess my point is, in

the art world, everything is arbitrary. It’s not a given that

those who get attention have earned it by developing a substantive

voice and quality doesn’t guarantee prominence. With that in mind,

maybe the middle way is the best course of action. For our scene to

get prominence we need to draw attention to ourselves. Controversy

works nicely. After we shock some sensibilities the spotlight will

turn our way and, at that critical point, we would need to display

substance, which we’ve got; act with shallowness first, end with a

display of quality. Our local scene would then get to enjoy the

fruits of our efforts… until Denver’s scene takes it

away.

Gavin:

What do you think of the galleries we have in town and around the

state, and the work they do to promote local art?

Ryan:

I think the galleries are doing the best they can. Everything is

about survival. The gallery needs to sell art and the artist needs

to make enough money to keep making art. The two don’t always

connect.

Gavin:

What's your take on Gallery Stroll as a whole and how it’s doing

today?

Ryan:

I haven’t done the Gallery Stroll for some time now. I love the

idea of it and when I have gone I’ve enjoyed it. I’ve been a bit

anti-social lately... it’s something I need to work on.

Gavin:

What can we expect from you over the rest of the year?

Ryan:

After the Finch Lane show, I’m not sure. Like I said, I’m in

adaptation mode so computer sculpting and design are where my

attention is focused. Last month I did participate in a group

sculpture show, "Conjoined - In 3D", at the Copro Gallery in Santa

Monica, California. A talented friend of mine, painter Chet Zar,

curated the show and it was a resounding hit. I’ve been invited to

contribute to its sequel next year. So I have that. Also I

helped out on some alien designs for a film "Battleship" that I think

comes out this year. It’s being directed by Peter Berg who did "Hancock" and "Friday Night Lights". I think he is preparing to remake "Dune", which is intriguing. Also, last October I was one of a team

of artists that helped Director Guillermo Del Toro with trying to get "At The Mountains Of Madness" green lit. Del Toro took all of our

designs, sculptures, etc. for a presentation to Universal. I’m not

sure of the project’s fate but I was grateful to play a small part.

So we’ll see what happens.

Gavin:

Is there anything you'd like to plug or promote?

Ryan:

What a fun question to get. Yeah, in fact there is. I’m

currently helping a friend, Christopher Salmon, who just received

funding to direct an animated short film based on Neil Gaiman’s "The Price". Another friend, Dave Laub, whom you’ve interviewed, is

helping out as well. The three of us go way back and are having fun

working out the book’s character designs. It’ll be cool. If

anyone is curious to learn more they can visit the following our website. Also, for those interested, you can check out my

portfolio/blog. Thank you Gavin for

your interest and support!

| Follow Gavin's Underground: |

|

|

|