Buzz Blog

Cannabis Compromise

If you feel strongly about legalizing medical cannabis in Utah, you still need to vote next month.

- Enrique Limón

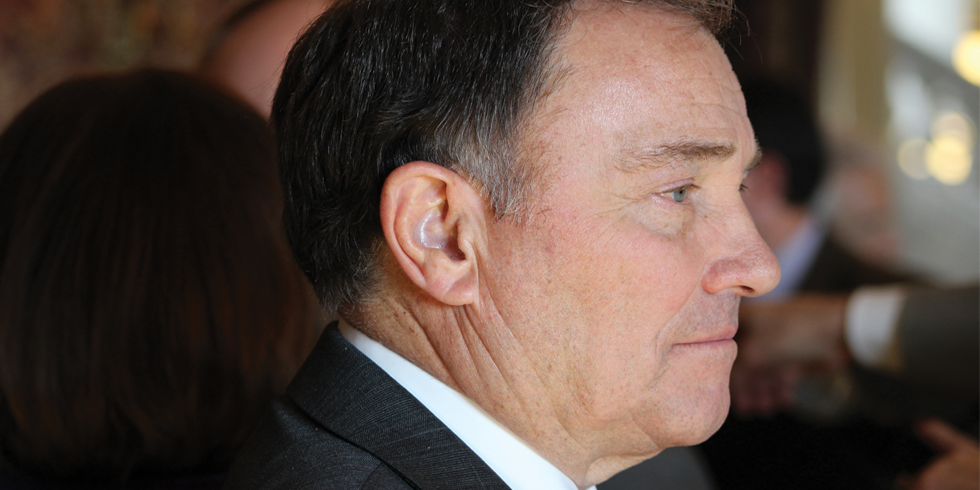

- Gov. Gary Herbert

Despite a recently announced compromise and special legislative session, there’s still no guarantee Utahns will have legal access to medical cannabis after the Nov. 6 midterm election, Hinckley Institute of Politics Associate Director Morgan Lyon Cotti, says.

“This compromise was made by people, in part, who will not be in office,” Cotti says of outgoing Senate President Wayne Niederhauser and House Speaker Greg Hughes. “If voters want the proposition to pass, if they want medical marijuana, they need to vote.”

Niederhauser, Hughes and other faith leaders and legislators held a news conference at the Capitol last Thursday to tell Utahns they’d reached an agreement on a state-run medical cannabis system that differs from the Proposition 2 initiative that will be on the ballot in next month’s election.

Utah laws allow legislators to make adjustments to ballot initiatives after they’ve been approved by voters. Alex Iorg, Utah Patients Coalition’s (UPC) campaign manager, says his committee anticipated amendments would be made to Prop 2 if it passed. Being a part of the compromise discussions allowed UPC to have a voice in how state lawmakers would change the initiative.

The new proposal would amend several key aspects of Prop 2. Among the most notable distinctions is that authorized patients would no longer be able to grow their own cannabis plants after Jan. 1, 2021, if they did not live within 100 miles of a dispensary. This is a much-maligned provision of Prop 2 that Gov. Gary Herbert has previously spoken out against because he fears the state would “lose control” of its oversight of medical cannabis, bringing Utah closer to recreational marijuana.

Iorg says the so-called “grow your own” portion of Prop 2 was written to ensure the state set up its medical cannabis system in a timely fashion. “We had a really good suspicion that was going to be removed almost immediately,” he says.

Under the compromise, qualifying patients would get their medical cannabis from one of Utah’s 13 local health departments or from one of five privately owned medical cannabis pharmacies. Because the “central fill pharmacy” would be run by the state and not a private facility, Iorg says Utah would need to get approval from the federal government, since it would be distributing a substance still deemed illegal under federal law. It’s unclear how the feds would react, he says, but the privately owned pharmacies would allow for a dual system of distribution that doesn’t solely rely on the state. “We’re nervous, because right now it is a compromise we agreed with, and we did so in good faith, but we’ll never stop worrying about it until it’s actually implemented and there’s a law on the books,” Iorg says.

Also modified in the agreement is the list of qualifying conditions that allow for patients to be eligible for medical cannabis. Iorg says such lists were “tightened up” by removing generalized medical terms that are in Prop 2. “We don’t feel like very many patients will be left off the compromise,” he says.

Not all lawmakers are supportive of the deal. “My concern is unveiling this compromise a week prior to ballots going out,” Rep. Angela Romero, a Salt Lake City Democrat facing reelection, says. Four weeks from the midterms, Romero says she knocked on doors over the weekend to talk with voters. Naturally, the cannabis compromise came up in their conversations. “They’re not supportive of us going into special session,” she says of the people she spoke with. “They want to see Prop 2 passed as is.”

Romero warns that a compromise could, “supersede the will of the people,” considering the high levels of public support for Prop 2. “Why are we, as elected officials, going to change that? To accommodate who?” she asks.

Cotti says the margin of victory matters on an initiative like Prop 2. If it’s overwhelmingly passed, voters send a clear message to the Legislature that they’re in favor of medical cannabis. If it passes by a smaller margin, Cotti says, lawmakers might feel more comfortable passing legislation that’s less comprehensive.

Cotti says it’s tough to predict voter turnout in the midterms, so it’s unclear how last week’s compromise could affect participation in the upcoming election. But she suggests Prop 2 supporters like UPC will need to work hard to keep public excitement up so people don’t assume medical cannabis is a sure thing, regardless of whether they cast a ballot. “This issue isn’t decided, and their vote is important,” Cotti says.