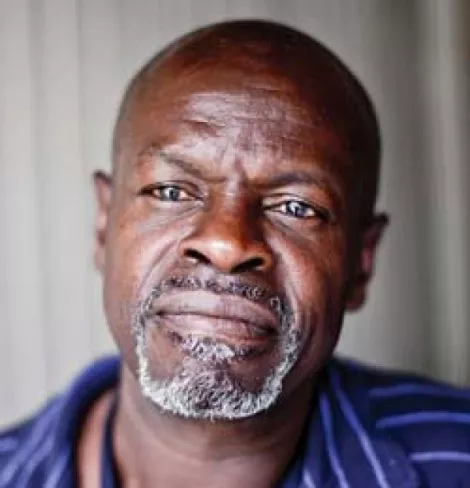

“Mr. Miller,” the Utah state prison guard said. “Pack up your shit and get out.” Harry Miller stood in his cell and cried uncontrollably, as cellmates put his few possessions in a box. “I figured I’d never get out,” he says. “I was just too happy to move.”

As the 53-year-old walked through the prison just before 2 p.m. on July 6, 2007, other prisoners clapped and cheered the African-American from Donaldsonville, La. In 2003, a 3rd District Court jury convicted him of aggravated robbery, and Judge Sheila McCleve sentenced him to five years to life. He didn’t do the crime—snatching a woman’s purse at knifepoint—he told fellow inmates, because he’d been thousands of miles away in Louisiana recovering from a stroke when the crime was committed.

“Taking somebody’s life away, that’s hard,” Miller says, reflecting on his four years of hard time in a growly, Southern accent. “Losing all those years I’ll never get back again.”

In prison, he says, you accumulate “the weight” of worrying about doing or saying something that earns you additional prison time. As he walked out of the gate and felt the sun on his skin, “all that weight left my body.”

Jensie Anderson of the Rocky Mountain Innocence Center [RMIC] hopes to have Miller declared “factually innocent” under a 2008 statute so he can receive $115,000 in compensation for his three years behind prison bars post-sentencing. (A year Miller spent in jail awaiting trial is apparently not included.) Anderson—a University of Utah law professor who runs the federally funded nonprofit RMIC’s innocence clinic staffed by law students—says the evidence of Miller’s innocence is simple: “Harry wasn’t in the state [at the time of the crime]. I have no doubt of that. It’s a simple case of mistaken identity. Not only was he not in the state, he was ill, recovering from a stroke.”

Miller’s wrongful conviction highlights the issue of faulty eyewitness identification. Nationally, out of 273 inmates exonerated of their crimes through DNA testing, 204 of the convictions involved eyewitness misidentification. Even more disturbing, national eyewitness expert and University of Iowa psychology professor Gary Wells says, conservatively, only “5 percent of eyewitness-identification cases […] can produce DNA tests to ‘trump’ an eyewitness identification.” This means that for every one of the 204 exonerations, “there should be another 19 [wrongful convictions] that could never be overturned by DNA because there was no DNA evidence to be analyzed.”

Miller’s tragedy is inevitably bound to that of his alleged victim, former Salt Laker Julia Smart, who not only lost the justice she thought she had after he went to prison, but also arguably has to wrestle with her own guilt that she helped put an innocent man behind bars. For the eight jury members deliberating on faulty evidence, finding an innocent man guilty must similarly have echoes of guilt and anguish.

Anderson notes that Utah is one of only two states that have innocence statutes on its books. Indeed the Utah Attorney General’s Office pushed hard for Utah signing into law the 2008 Exoneration and Innocence Assistance Bill. “This new law [also] affirms our obligation to provide a compassionate response in those rare cases where the wrong person is sent to prison,” Attorney General Mark Shurtleff said in a press release.

So why, wonders a bewildered Anderson, “do they now not want anyone to use it?” She is referring to the AG’s decision in late May to appeal Deborah Brown’s exoneration of a murder a judge ruled in March she did not commit after she had served 17 years in prison. But Miller’s case is different. Attorneys on all sides, including the attorney general, agree his case is rare. Given that rarity, argue Miller’s supporters, why did it take the legal system so long to first release an innocent man, and now, hopefully, acknowledge to the world that a mistake was made? If Miller were an example, Scott Reed of the attorney general’s office says, “of one time [when the system was fallible] and we accept that, then we are going to correct it.”

Anderson says Miller, who currently works part-time as a landscaper for Salt Lake County, was “failed by the system through the police investigation, through his arrest, his trial, his appeal.” His petition to be declared factually innocent is “an opportunity for the system to at least attempt to make it right.”