But there is an end. If developers and politicians and the market economy have their way—and there is little reason to believe they won’t—a day will come when the population will have grown to the point that the Beehive State will simply not have enough water to meet demand.

Rather than focus on using less water (Utahns are widely regarded as among the most wasteful water users in the nation), Utah officials are busy trying to figure out how people can continue using lots of water long into the future.

In order to sustain Utah’s green landscapes and growing suburbs, state leaders intend to spend $2 billion on massive pipeline projects. One will dip a straw into Lake Powell to sprout more homes in the desert of St. George, while the other will siphon water from the Bear River.

These projects, combined with modest conservation efforts and the repurposing of agricultural water for culinary use, will get Utah through the year 2060, when the state’s population is expected to have doubled to 6 million souls.

The following stories speak to Utah’s water future, and whether the state’s efforts to step into this future are well advised. Some say they’re not.

Every single person interviewed for these water stories, though, agreed on a seminal fact: Utahns could be saving much more water than they are.

With that in mind, raise a glass of water and toast Utah’s great and abundant water. Gulp it down, and as your throat thaws from the water’s chill, take a moment to reflect on how you personally use, and perhaps even waste, water.

Then do something about it. Because when it comes to how you consume water, your choices are all that matter.

A Pretty, Dry State

Utahns are nearly the biggest water consumers in the country. What does that mean for the future?

Rare is the summer day when Utah gutters aren’t running with sprinkler water. All across the state—from the parched red earth of Dixie to the fertile farmland of Cache Valley—strings of century-old brick homes along main streets and the droves of new geometrically intricate suburbs are buffered from the asphalt streets by yards and yards of shining green grass.

Call it waste, or call it abundance: Even though Utah officials say that the state is headed toward a water emergency that will soon require construction of $2 billion in water projects, Utahns use, and will continue to use, boatloads more water than their neighbors across the West.

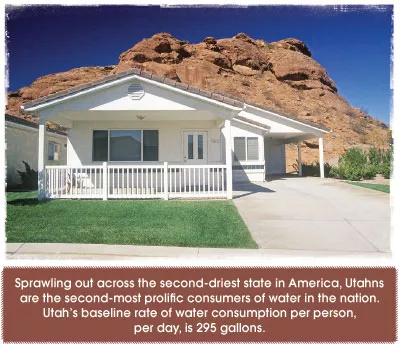

Sprawling out across the second-driest state in America, Utahns are the second-most prolific consumers of water in the nation. Utah’s baseline rate of water consumption per person, per day, is 295 gallons, according to the Utah Division of Water Resources. Only Nevada uses more. This number fluctuates from year to year, but is important because water officials have used it as a starting point for conservation efforts and future projections. When Utah achieves a statewide conservation goal of slicing its thirst by 25 percent over the next 11 years, its consumption will still far exceed the 130 gallons New Mexicans consume, or the 165 gallons used per person in Denver.

Rock-bottom water costs, typically reliable and abundant water sources and a longstanding lust for non-native plants and thirsty Kentucky Bluegrass (60 percent of Utah’s municipal water is sprayed on outside sources) contribute to Utah’s high water use.

When the state’s population doubles by 2060, as state census data predicts, the Beehive State’s water system will be strained. But few water planners seem truly worried. Through a combination of modest conservation, more efficient delivery and colossal water projects, this demand will be met.

Those who criticize the last piece of this puzzle—the development side—say Utah could provide enough water for its booming economy and population if it merely sought to no longer be among the thirstiest water consumers. Conserving, they say, would save taxpayers billions while leaving the strained Colorado and Bear rivers—the sites of the state’s future water projects—alone.

Even water managers say conservation could be much more robust, and perhaps negate the need for these projects.

But Utah’s proud pioneer heritage, forever transfixed on LDS Prophet Brigham Young’s adherence to the idea of making this desert—Zion— “blossom as the rose,” and a distaste for government intrusion, persists. And Utahns really like their green landscapes, costs be damned.

“It goes back to people can have their landscapes the way they want,” says Eric Millis, director of the Division of Water Resources, the state agency charged with ensuring Utah has enough water now and in years to come. “We’ve had this legacy, maybe you’d call it, of having green landscapes.”

When it comes to conservation, Millis says, the state is doing enough. Whether they even noticed, Utahns have already gone a long way toward meeting the state’s conservation goals. Millis says water consumption has dropped by 18 percent since 2000, leaving him confident that the remaining 7 percent will be reached easily, and perhaps even ahead of schedule.

But once the state reaches its goal, which would cut the per gallon usage to 221 gallons per person, there is no statewide conservation plan.

“They don’t disagree with that,” says Zach Frankel, executive director of the Utah Rivers Council.

Frankel says Millis and other water managers don’t want Utahns to conserve because they want to build their way into the future. And the comedy of it, Frankel says, is that Millis and his colleagues across the state have been effective at convincing Utahns that the state is gripped by a water crisis to get more projects built, while simultaneously declining to save more.

“This claim that we’re running out of water is a farce,” says Frankel. “But if you’re trying to make the public receptive to spending its tax money on destructive water projects, making them afraid of the future is the way to do it, and that’s what the Division of Water Resources has been doing for 20 plus years.”

Water On the Cheap

Critics of Utah’s sky-high water use believe one of the key elements to promoting waste rather than conservation is the dollar value the state puts on its most valuable resource.

A DWR study shows that 1,000 gallons of water in Utah costs $1.34—43 percent below the national average and 45 percent under the average for other Western states.

The reasons for these low costs, the study shows, is the abundance of water in the state’s mountains and streams that wets the majority of Utah lips. This water comes courtesy of the hundreds of inches of annual snowfall in the mountains, which is stored, protected and naturally filtered as it trickles downstream to water treatment plants. Since much of this supply is gravity-fed, costs of transporting the water is low. And because these mountain sources are clean, the cost of treatment is also low.

No one says that Utah’s water delivery system is anything less than wonderful. But for Frankel, this fast and easy water should be valued and conserved, not frivolously wasted.

“We give lots of lip service to the idea that water is valuable,” he says. “But we don’t price it like it’s valuable. We price it like we don’t care about it. Water is given less value than dirt. And I don’t mean to disparage dirt. But water needs to be valued appropriately so people don’t waste it.”

In the name of conservation, other states have instituted far more rigorous pricing structures. Some Utah communities have tiered pricing, where users pay more if they use more. But these prices generally lag behind other Western cities.

For example, Frankel points out, during July—peak water season—the average home in Seattle uses 4,000 gallons of water. In St. George, average per-home use is around 28,000 gallons in July, and residents pay just over a buck per thousand gallons, compared to the nearly $6 paid in Seattle.

Of course, Seattle is much wetter than Utah. This means lawns and landscaping requires less watering to stay green.

And here lies a conflict: Utah officials say the aridity of the state justifies high outdoor water use. Some would say, however, that this is backward—because Utah is dry, it should use water more wisely.

But Utah’s water isn’t as cheap as it seems. Water rates in much of the state are subsidized by property taxes. Studies conducted by DWR show that only 8 percent of the nation’s water suppliers rope in revenue through property taxes, but most water providers in Utah utilize taxation.

Water managers defend this practice, saying the predictable revenue streams give their organizations stability and help them borrow money at lower interest rates.

Property tax “gives you a more secure source of money,” says Ron Thompson, general manager of the Washington County Water Conservancy District. Thompson has lobbied hard for the Lake Powell Pipeline, a $1 billion project that has been blessed in Utah with a legislative decree and is nearing the completion of a $25 million environmental impact study.

Thompson doubts that raising water prices in his district would stanch water use. As an example, he says, when he was a boy, gas cost under 20 cents a gallon. “I don’t think the fact that I pay $4 now means I drive any less,” he says. “I don’t drive any less.”

Frankel, though, says shedding the property tax would allow water consumers to see a truer picture of water costs. And with modest rises in prices, Utah, like its neighbors across the West, would waste less water.

“It’s nuts, it’s perverse,” Frankel says of the property tax, noting that in fiscally conservative Utah, a tax of this nature flies in the face of letting the market economy determine the price of the commodity. “It’s why we have the cheapest water rates; it’s why we have the highest per-capita water use.”

Utah water managers will continue protecting these low costs, even if hiking them could save water. The DWR report on Utah’s inexpensive water notes that bank-busting water projects will raise water costs in Utah, but due to the state’s “unique climate, geography and other factors … average water bills are likely to remain below those of other areas of the West and the nation.”

There Is Water All Around

As more and more farmland is gobbled up by housing tracts, less water is needed for agriculture use. Currently, around 85 percent of Utah’s water goes to agriculture.

With ever more houses sprouting along the heavily populated Wasatch Front, farmland has disappeared. What hasn’t disappeared, though, are many of the canals and the water that fills them. During summer months, many of these canals sit stagnant, filled with water that never makes it into Utah taps.

DWR studies have shown sharp decreases in the need for agricultural water diversions in the Jordan and Weber River basins. For example, in the Weber River Basin, 308,800 acre feet of water was diverted to irrigate cropland in 2007. The study shows only 161,200 acre-feet will be needed in 2060, leaving a 147,600 acre-feet surplus—enough water to supply more than 600,000 new residents.

For the Salt Lake Valley, the amount of water diverted for agricultural use is around 143,000 acre-feet. The state’s 2010 water plan for the Jordan River notes that by 2030, and perhaps much sooner, agricultural needs in the Salt Lake Valley will be “nonexistent.”

Millis says the canal water is not being wasted, and that by 2060, utilizing this water for residential and industrial use will account for 15 percent of the state’s needs.

“I think that conversion process is happening,” he says. “It’s certainly something that we’ve encouraged to meet the needs.”

Frankel, though, says the staggering amount of water in the Weber and Salt Lake Valleys alone—combined with ambitious conservation—could fully provide for Utah’s needs long into the future. The basis for this argument is that acre for acre, homes, streets and sidewalks use far less water than fields of crops.

“These canals are everywhere,” Frankel says. “This is clearly not a good use of water. They’re ignoring this water source.”

But fully utilizing this water, Frankel says, could eliminate billions in water projects, and when no one’s looking over a water manager’s shoulder, he says, “they’ll choose the $2 billion every time.”

Deaf Ears No Longer

Frankel doesn’t hold back when he talks about Utah’s water picture. Plain and simple, he says, Utahns are “the most wasteful water users in the United States.” And in order to get big projects built, the DWR has been “cooking the books to manufacture a water crisis.”

His assertions have gained an audience.

In November 2013, a four-person committee of high-ranking legislators met to receive a briefing from the state’s Office of the Legislative Auditor General. An item of business was to ask for new audits, one of which set its targets on the DWR.

Senate President Wayne Niederhauser, R-Sandy, referenced the possible surplus of water that’s building as agricultural use is consumed by development.

Far from a water crisis that would warrant billions in spending, Niederhauser said, “it seems that they’re building treasure chests of water that they may not need for the future.”

James Behunin, the legislative audit supervisor, confirmed that an audit on the DWR is in progress.

“There’s some really interesting issues with water in Utah,” he says, noting that a full audit of the agency hasn’t been done in decades. “We’re going to look at how we handle our planning and regulation and just see whether our state agencies are proceeding in the most efficient, effective manner possible and in the best interest of the citizens of Utah.”

The Billion-Dollar Straw

In addition to being costly, the Lake Powell and Bear River pipelines will have impacts on the environment.

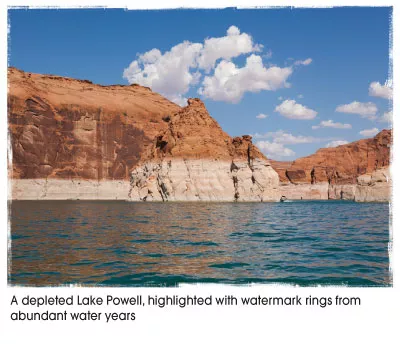

The taxed Colorado River, which supplies water to around 40 million people, has withered under years of drought. This has left Lake Powell less than 40 percent full, although it will likely rise slightly this year due to healthy snowpack in the Rocky Mountains.

Utah’s insistence on building the Lake Powell pipeline is rooted in the fact that it does not currently utilize its full allotment of the Colorado, as specified in the Colorado River Compact of 1922.

Watching water-needy areas like Southern California and Las Vegas get this water has chapped many a Utah politician.

Washington County’s Thompson spells it out. The pipeline, he says, “allows us to keep the water we’re entitled to. It runs downhill unless we use it.”

And now, whether Utahns truly need it or not, a portion of the state’s allotment is scheduled be siphoned out of Lake Powell, with most of it arriving in Washington County.

To fuel continued growth in St. George—which, Thompson says, has returned to the pre-Great Recession rate of selling and building homes to the tune of 400 a month—Washington County will need that water to fill the bellies and water the lawns of the projected 600,000 people who are expected to live there by 2060—a 416 percent jump from today’s 144,000 residents.

The alternative, Thompson says, is that Washington County doesn’t grow to that extent. And the area’s reliance on the fickle Virgin River watershed, where most of its water comes from, won’t accommodate massive growth. This year, Virgin River snowpack is less than 40 percent of normal, making Thompson certain he and his colleagues will be unleashing strict water conservation methods in the months to come.

Lake Powell would alleviate these concerns. “Without Lake Powell, there’s not a big future here,” he says.

Mike Noel, a stalwart Republican member of the state’s House of Representatives from Kanab, is also the general manager of the Kane County Water Conservancy District.

Noel’s district would receive a share of the water in the pipeline, which he fervently supports.

But Noel, who is known for his sharp critiques of environmentalists when he’s on Capitol Hill, has implemented a number of water-conservation efforts in his area, including more aggressive meter-reading and a tiered rate structure.

Still, he believes the pipeline is necessary, and that if it were the will of the people to conserve, they would elect people who oppose the pipeline and resolve to change the way they consume water.

“There’s no question about it that there’s an ability to conserve more,” he says. “What it’s going to require is that people recognize ... that it’s going to be a different community if you have more conservation.”

While the DWR’s Millis estimates the Lake Powell pipeline could be built by 2025, the Bear River pipeline, which aims to redirect a portion of the river’s flow into a pipe to supply the Wasatch Front, won’t be needed for at least a decade later.

Diverting the Bear River, Frankel says, would devastate tens of thousands of acres of wetlands in the Great Salt Lake, jeopardizing the largest wetland between the Mississippi River and the Pacific Ocean.

Fueling population growth and maintaining landscaping might rank high on the list of importance for many Utahns. But Frankel wonders at what point Utah will realize it cannot afford to pillage every water source it has and sacrifice it on the altar of growth.

That Utah is home to the Great Salt Lake and the Colorado River, Frankel says, makes the Beehive State a natural wonderland. And Utahns have been charged with ensuring these water sources survive long into the future.

“It’s time that Utah catch up to the rest of the pack and embrace an ethic of stewardship of nature instead of annihilation,” he says.