Page 2 of 7

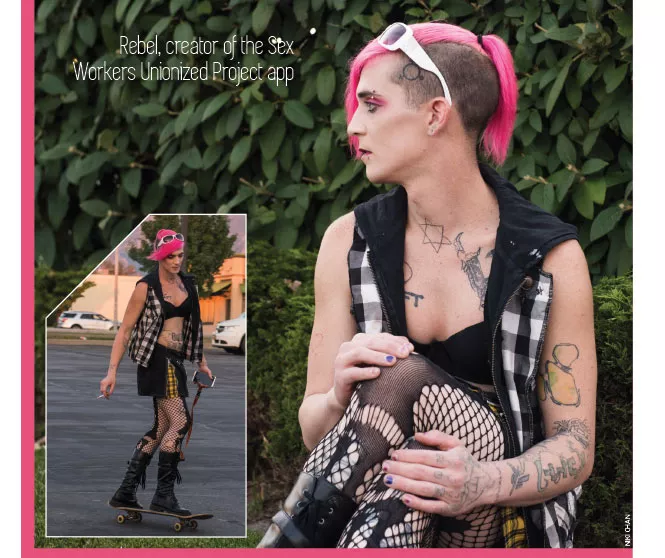

That experience led her to develop a mobile phone app called Sex Workers Unionized Protection (SWUP), wherein sex workers anonymously upload the contact info of concerning clients, along with descriptions and comments. When a client who's on the database calls, that call will automatically be flagged, letting the sex worker assess the level of threat identified by others. While 90 percent of the client comments are negative, Rebel also flags clients with whom she had a positive experience, such as "one dude who tipped me $500 for a 20-minute session."

In sex worker parlance, a "bad date" is an encounter with a client that could result in wasting her time, being threatened, abused or hurt. While there are numerous local, regional and even national bad-date list websites, nonprofit advocacy group Sex Workers Outreach Project's Katherine Koster says some are behind paywalls and impoverished sex workers can struggle to access computers.

While clients have long posted often disturbingly detailed "reviews" of their encounters with sex workers on various websites, Rebel's app allows them to turn the tables to some degree, rating clients and warning their peers if they have concerns. Such a list is important because "a lot of people committing violence against sex workers are serial perpetrators, not just a one-shot thing," Koster says. Rather than report a sexual assault to law enforcement, she says, which might result in her getting arrested, reporting it to a bad date list might prove safer and more effective in terms of warning other sex workers of a potential threat.

Its emergence comes at a time of disquiet for sex workers across the country who, since the sudden shut-down of adult ads on Backpage.com last month, are scrambling for work. This followed the October 2016 arrest of Backpage's CEO on sex-trafficking charges. Several sex workers City Weekly spoke to reported a dramatic drop in their income since the adult section of the site went dark, possibly because clients were uncertain where to look for them. While Rebel's app leaves Koster excited at the possibilities it offers sex workers to pool information about clients, loss of work because of the Backpage shut-down makes her fear that in the immediate future sex workers will return "to abusive work situations, relationships, back to street-based sex work," or end up homeless as they are evicted for non-payment of rent.

Rebel says 160 people were using the app from Salt Lake City before she decided to bow to requests from users that it be anonymous, which meant she could no longer keep track of the number of workers. She shows a reporter a few comments submitted to the app about clients. "Time waster, will ask for bareback and want to pay after," one worker wrote about a client seeking sex without a condom but refusing to provide the agreed amount before the act.

A 24-year-old escort who goes by Lana Del Shay, uploaded a number onto the app belonging to a man who she says offered her $200 for oral sex, then tried to force her to grope his genitals. After she repeatedly demanded "a donation"—language some sex workers use in the belief it will help them avoid arrest—he allegedly pulled out a cop badge and told her, "Now we're both implicated." She questioned whether he was law enforcement and eventually he returned her to her hotel.

Advocates for sex workers both nationally, like Koster, and locally welcome the app. Local advocate Gina Salazar regrets it has not been available before. "I wish somebody would have thought about it a long time ago before tons of girls ended up getting hurt, beaten or raped. It's probably as important as a condom," she says. "To me, it's a huge tool for harm reduction."

While technology in the form of Rebel's app may prove to be a powerful tool in improving the odds of keeping sex workers safe, the questions that surround Backpage shutting down its adult ads highlight both the boon many say it provided for independent sex workers and what Utah Attorney General's special investigator Nate Mutter calls its "double-edged sword," when it came to finding minors enslaved in the sex trade and prosecuting their traffickers.

Rebel says that Backpage "has been nothing but a safety net," providing regular income with which to support her family. Del Shay concurs. She says she was a homeless 18-year-old addict when she started "dating," after she was robbed of her shoes and money while sleeping in a park by North Temple. "If it wasn't for Backpage, I don't know what I would have done," she says. She made enough money to get off the street, rent a hotel room and eventually support her grandmother, relatives and her toddler.

Local anti-trafficking advocate Laurin Crosson says as a trafficked woman she preferred the street to meeting a client in a hotel room. "You can see the trick, look into his eyes," and based on her instinct she could turn him down or get in his car. In a hotel room, waiting for a client, there's very little chance to say no. "It's so much more dangerous and scarier," she says.

In the weeks following the shutdown, Rebel and LaShay both report a collapse in their income. "My business has been cut in half," La Shay says, who, like her counterpart, has had to rely on regulars to keep her going. "The last few days, I've been lucky to pay my room." They both fear sex workers will be forced to turn to the street to work, or to accept offers from a new wave of pimps who reach out to them online, parading pictures of cars and money along with the promise of money if they come to work for them out of state.

Law enforcement has mixed feelings about Backpage.

Mutter says the move is "good for the public; it takes away one piece of the tool that traffickers use to traffic their victims," particularly minors. At the same time, "it's almost a negative for law enforcement. One of our main objectives is to get the trafficker, but it's more important to get the victim out of that situation." If shutting down drives trafficking further underground, as some predict, he says the fear is they're not going to be able to rescue as many victims.

Given that the shutdown is only weeks old, he adds "it's too early to tell" how it will impact investigations and prosecutions.

Salt Lake City Police Department's Sgt. Mike Burbank, who heads the Organized Crime Unit, says that Backpage amounted "to almost a one-stop shop" for them, given it was where most local "johns" would look for sex workers. Within 15 minutes of his officers realizing it was gone, they found the same postings had been listed elsewhere on the site, such as date-seeking sections (women seeking men) or ads offering therapeutic massage.

Rebel hopes her app will not only gain traction among local and out-of-state workers, but will also lead to more dialogue among sex workers. As the name implies, she would like to see her peers "unionize" in some form. She also wants to see sex work legalized, and along with the move "take control of the industry out of the hands of clients," she says. "Having a tool like this available will help shift that power."