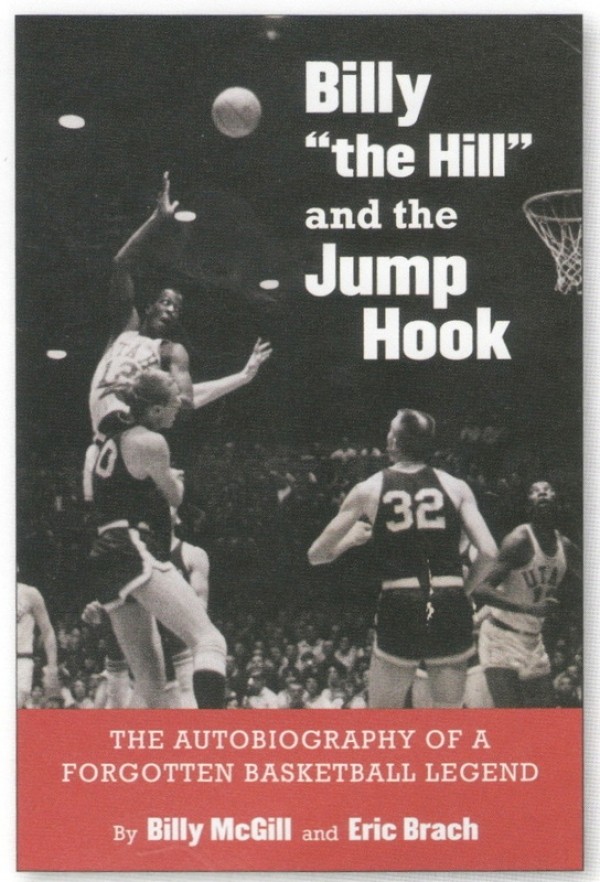

In more than 100 years of University of Utah basketball, one of the all-time greats to wear the red and white was Billy “The Hill” McGill.

While playing up on the hill at the U from 1959 to 1962, “The Hill” took the Utes to a Final Four, and in his senior year averaged a seemingly impossible 38.8 points per game—a figure made all the more amazing when you consider there was no shot clock or three-point line in that era. The 6-foot-9-inch center was the first practitioner of the jump hook, a shot you can see big men taking in any college or pro game today.

McGill’s performance in Utah made him the No. 1 overall draft pick in the 1962 NBA draft. Based on his college stardom, it was natural to assume that he’d go on to NBA championships and league scoring records. But in fact, McGill played for eight different teams in the NBA and the now-defunct American Basketball Association over five seasons, often in a backup role, before ending up out of the game at age 30. Just eight years after being the best player in the nation, McGill found himself homeless in Los Angeles.

Now, almost 50 years since fading from the cultural conceousness, McGill recounts his fame-to-rags-to-(spoiler alert)-eventual-middle-class-life in Billy “The Hill” and the Jump Hook: The Autobiography of a Forgotten Basketball Legend.

It’s a fascinating story, but as with any autobiography, we’re only getting one side of the story, and there can be gaps in the narration where a reader would like to know more.

For example, even though McGill was a high-school All-American in Los Angeles, California colleges and national powerhouses didn’t offer him scholarships. The book is frustratingly vague as to why; McGill hints that it may have been due to poor grades, but doesn’t provide anything definite. Some schools might have been scared off because McGill was coming back from a major knee injury and had to practically teach himself to walk again. He also had a difficult family background to contend with. Some coaches might have felt constrained by the unofficial “quota” for black players at the time, which said you could “start two at home and three on the road.”

If prejudice was a factor, it’s ironic that it ended up steering McGill to Salt Lake City, where he became the first African-American basketball player in Ute history. When he visited his first restaurant in Zion in the late 1950s, the official policy was a sign that read, “No coloreds”—but when the staff learned he was the new starting center at the U, they decided to make an exception. Thus began an uneasy truce where McGill’s accomplishments on the court led to acceptance from the community in some situations (e.g., getting one of the best tables at a swanky downtown restaurant after a big win) but not others (e.g., openly dating a white woman).

In 1962, McGill was the first overall pick of the Chicago Zephyrs, one of just nine NBA teams at a time when it was a fringe league, still more than two decades away from having its finals games broadcast on network TV in prime time. McGill’s struggles at the professional level can be chalked up to a variety of things: racism, knee problems, bad coaching, a league with only nine starting center spots, and just plain bad luck.

However, McGill’s biggest problem may have just been the way the game was played at the time. At a lean 6’9”, he was too small to play center in a pre-three-point-line game where everybody jammed into the paint for lots of physical play, yet his knee problems made him too slow to play forward. He was a classic “tweener” who didn’t fit into the rigid boxes that sometimes define positions in the NBA.

It’s a shame, because the McGill story would have been very different—financially at least—if he’d been born 50 years later. BYU basketball has its own story of a college scoring phenom who went high in the NBA draft and now can’t seem to find the right fit in the league for showcasing his talents. But while Jimmer Fredette may be frustrated with his NBA experience, he’ll walk away from the league having made more than $7 million, even if he never plays another minute. McGill never made more than $17,000 in a single season.

If nothing else, this book will remind basketball fans of one of the greatest players in college hoops history. Next time you see a big man jump off two feet and loft a one-handed shot from behind his head, think of The Hill.

BILLY “THE HILL” AND THE JUMP HOOK:

By Billy McGill and Eric Brach

University of Nebraska Press, 2013

$29.95 hardcover