- Niki Chan

What stopped Michael Coots that Saturday in September 2012 from going home and putting a gun in his mouth was that he could not remember where he lived.

The 54-year-old sat in his truck in shorts and flip-flops and struggled even to recall why he had left his Ogden home that morning. His life had no meaning and he wanted out of it. “I just wanted to get it over with,” he says now. “I wanted to stop the pain.”

But then the electro-mechanical technician looked through his windshield, saw a sign for Ogden Regional Medical Center, and, in a moment of clarity, realized that he was sick and needed help.

His brown eyes awash with tears, Coots took stock of his life with a doctor in the ER. Divorced once, his second marriage was now also collapsing. But more than that, he said, stress over his work at Hill Air Force Base, where he had been employed for 13 years, was destroying him.

The doctor called in a psychologist and locked the door. He told Coots that he was suicidal and needed to be hospitalized.

Coots panicked. He asked to go to the restroom and, as he was let out, twisted a guard’s arm behind his back, pushed him away and took off running, only to tumble to the parking lot asphalt as his flip-flops fell off his feet. Half a dozen medical staff and a security guard piled on top of him, strapped him onto a gurney and wheeled him into a barred room, where he spent the next week heavily medicated, monitored by the unblinking eye of a wall-fixed camera.

On the eighth day, after filling out a 500-page psychological evaluation form and being interviewed by a judge on closed-circuit television, Coots was found to be no longer a danger to himself and was released.

If Coots had managed to find his way home that Saturday morning and killed himself, it would have made him one more statistic to add to the 40 civilians and seven military employees of Hill Air Force Base who, between 2006 and the end of 2013, took their own lives, according to previously published statistics figures the base released to City Weekly.

Coots says the base is a toxic world where supervisors and managers use bureaucracy to persecute people to the breaking point. Coots and others—none of whom would go on the record for fear of retaliation—say it’s also a world filled with hypocrisy, where employees take mandatory classes on the 2002 Notification and Federal Employee Antidiscrimination and Retaliation Act, which claims to have zero tolerance for harassment, and attend assemblies where military brass urge employees to look out for each other. Despite all this, Coots says, no one would listen to his concerns of workplace retaliation.

“That was the reason for all my desperation,” he says. “No one cared.”

In November 2013, a little more than a year after his almost-suicide, Coots filed a health discrimination complaint with HAFB’s Equal Opportunity Office, alleging he had been discriminated against because of his age and a 2006 heart-bypass surgery.

Hill declined to address Coots’ complaints, citing the ongoing litigation.

Coots provided City Weekly with several reports prepared by investigators with the Equal Opportunity Office that detailed both his claims and documentation and the responses of colleagues and supervisors to his complaints. The first investigator made no conclusions, but several people she interviewed supported Coots’ allegation that he was being driven out of the base by disgruntled management, who, as one maintenance mechanic put it, were “maliciously trying to fire him.”

Coots is a fighter; his father boxed for money in back alleys during the Great Depression and taught his son a love of the sport. Now, Coots is determined to fight for himself and others like him, who’ve been sapped of the will to live because of their working environment.

But in boxing, Coots says, “you know where you stand, you know who you are up against. You have the opportunity to defend yourself, you can look them in the eye. With the government, you’re fighting a vast entity that is elusive in every way, and you don’t know what’s the truth, when you’re being entrapped. It’s like trying to fight the invisible man; it’s like fighting a ghost.”

RAISING THE DEAD

Coots and his two best friends, Brian and Jimmy, were hell raisers as kids, chasing each other on dirt bikes through the small town of Lemont, Ill., just outside Chicago. Brian’s sister Laurie Zuro recalls the then-redheaded Coots as being old-fashioned and respectful, someone who “loved to learn, always watching how things were done, and then doing them better.”

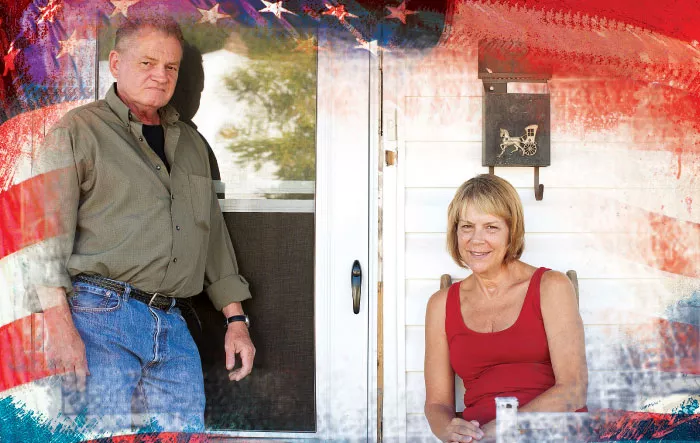

- Niki Chan

- Michael Coots finds solace in spending time with his childhood friend laurie Zuro in the ogden home they share.

Brian enlisted in the military in 1977, an act that eventually inspired Jimmy and Coots to follow suit, because, Coots says, “It was the right thing to do.” Coots enlisted in the Air Force in 1984 in Chicago when he was 25. He attended jet school for four months, then went to New Mexico on active duty as a jet-engine technician. But in October 1988, his father died, and his mother, suddenly alone after 52 years of marriage, wanted him to come home. Although he had only one more year of active service left, he made a deal with the military that he would do six years of weekend duty with the Air National Guard so that he could return to Lemont.

But in the wake of Desert Storm, Coots’ knowledge of jet-engine propulsion made him invaluable, as the Air Force desperately needed replacements for their sand-damaged jets. He returned to full-time active duty, putting in 12- to 14-hour days building as many engines as he could, jet fuel running into his cuts and burns.

His supervisor wrote that Coots’ work at the jet engine shop reflected the “kind of spirit [that] is necessary to national defense. While you did not actually deploy, your mission here at O’Hare was equally important in the ‘Big Picture.’ ”

Coots says his service “gave me a sense of duty and honor. It made me feel good to be able to do well there.”

Shortly after the refueling wing returned from deployment, the base commander called employees into a hangar. To his surprise, Coots was awarded the Meritorious Service medal, the equivalent, he says, of a Bronze Medal for non-combat military personnel.

Coots moved to Utah in 1994 and joined “Team Hill” in 1999.

Hill Air Force Base is a world unto itself. It’s fenced off, with guards at every exit and anonymous voices that blare from external speakers, counting down to lightning strikes or reminding employees to use safety glasses. The 6,650 acres, straddling Layton and Clearfield in Davis County, is dotted with almost 1,500 windowless buildings and 11 huge hangars, plus a 13,500-foot-long airstrip from which high-tech fighter planes roar into the sky.

- Niki Chan

- Hill’s Ogden Air Logistics Complex, where maintenance of fighter aircraft is performed

Hill is also littered with aging machinery, like a 1960s altitude chamber the base used to test re-entry rocket motors for intercontinental ballistic missiles, simulating altitudes in excess of 160,000 feet. When the chamber “gave up the ghost,” Coots and his team were called in. The 649th Munitions Squadron commander, Nathan Ply, described in a 2003 memo how, with no documentation or repair manuals, Coots got it to work “as well now as it did on the day it was built.”

According to 35 commendations and letters of gratitude from Hill staffers, Coots proved himself to be a highly valued mechanic, maintaining and salvaging machines from disposal that saved “the USAF untold dollars in machine replacement and down time,” according to a 2009 letter written by civilian manager Shane Olsen.

The concept of the chain of command is fundamental to the Air Force, where you are accountable to your immediate superior. If an employee is not satisfied with the response of that immediate superior, he or she has the right to go up to the next level.

Coots worked under five levels of supervisors, all civilians. The first level manages workers, handing out work assignments. The second level, Coots says, carry down orders, questions and disciplines from the third level to the first. The fourth and fifth levels are “figureheads,” at least for those working on the shop floor, he says.

Hill officials, Coots says, “realized my abilities and put me in charge of maintaining a lot of equipment. I was very busy, and busy means being happy.”

In December 2006, the 48-year-old Coots had heart-bypass surgery. After he returned to work, his third-level supervisor, Scott Boothe, asked if Coots “could get the second shift to perform their duties and straighten up,” effectively making him their supervisor.

Coots says his management style was to work on improving employee relations. When “someone did something good, I’d ask for an on-the-spot reward for that person,” he says. Along with a “cheesy” item like a hat or a T-shirt, Coots would get a letter of appreciation typed up.