It’s that time of year again when the more than 12 million members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints turn eyes and ears to Salt Lake City for the semi-annual General Conference. It’s a time when the faithful flock to the capital of Zion in their Sunday best to hear words of wisdom from their prophet, apostles and other church leaders, who dispense sage advice and wisdom like a kindly grandfather hands out Werther’s Originals.

While the conference is an opportunity for members to be reminded of valuable church lessons relating to current issues and old-time values, it’s also an opportunity for Mormons to define themselves. It’s likely a welcome opportunity for the faithful, as the media has recently been gripped by Mormon mania. Two contenders for the GOP presidential nomination, Mitt Romney and Jon Huntsman, have brought their LDS faith with them on the campaign trail. Even the creators of South Park have their own take on Mormonism with their Broadway smash hit The Book of Mormon musical.

The world wants to know—what is a Mormon? Where did these pleasant people with their polygamist pasts come from? What’s with the green Jell-O? What’s with Satan being bros with Jesus?

While misperceptions and myths abound, what is known is that Mormons believe Jesus came to America, they believe in The Book of Mormon and they believe the church president is a living prophet with a direct line to God. But, as individuals, they believe more than that.

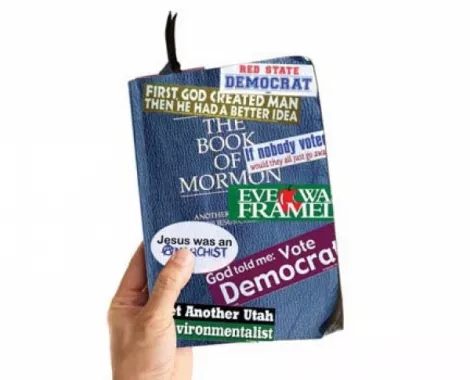

Despite stereotypes, you can’t place a name badge on a Mormon that simply says “White/Republican/Male.” The truth is that within the church there is a diversity of Mormon thinkers and members who find their faith also supports their beliefs in anarchy, feminism and protecting the environment. Unlike many conservative Utahns, these members find the lessons of their old-time religion completely consistent with radical or progressive beliefs. It’s not that these Mormons don’t fit the mold—it’s just that their unique beliefs make them the fruit cocktail in the jiggly green mass of the church’s membership.

Anarchy in the HK (Heavenly Kingdom)

The seven months that Mormon anarchist/socialist/pacifist William Van Wagenen lived in Baghdad during the aftermath of Operation Iraqi Freedom were a lesson in power and destruction. While volunteering for a small human-rights organization in the suburbs of Iraq’s capital, a regular morning ritual for Van Wagenen was to awake at dawn to the sound of artillery explosions.

“In the morning, I’d climb to the top of the apartment building and see smoke rising usually four or five blocks away,” Van Wagenen says.

Life in Baghdad then was bedlam at best, as U.S. military forces, Iraqi security forces and myriad militias and resistance factions fought for power on the streets, while kidnappings and murders became routine aspects of life in the newly liberated Iraq.

The scene could be described as anarchy. But that’s not how Van Wagenen sees it.

“There are two different meanings to the word anarchy. There’s the pejorative usage, which in Iraq is like murders, killing and chaos,” Van Wagenen says. “But anarchy as a political philosophy is just the opposite; it’s a highly organized society, but one in which there is either no political authority, or at least a very decentralized, weak authority.”

Van Wagenen, who founded the Mormon Worker, a monthly publication touching on Mormonism’s radical anarchist and socialist roots, found in Iraq a horrifying example of the tyranny of coercive government authority. But the lifelong member of the church who grew up in Utah, attended Brigham Young University and later studied theology at Harvard, was first introduced to anarchy by, surprisingly, a friend from his LDS mission in the Frankfurt area of Germany.

Van Wagenen had been off his mission for two years and was in Germany touring Europe with the BYU soccer team when he went to visit a friend from his mission who was an anarchist. That friend had a message to share and a book that Van Wagenen needed to read—a German book about the Haymarket Square riots in 19th-century Chicago. Those riots resulted in a public bombing that authorities later blamed on German socialists and anarchists in the city. The anarchists were summarily imprisoned and executed, not because of evidence they’d committed the bombings, but because of their radical beliefs.

This introduction to anarchism was eye-opening for Van Wagenen, but it wasn’t the first time he had read about the anarchist way of thinking.

“It just seemed like these are ideas, in secular form, that are taught in Mormon books of scripture,” Van Wagenen says.

The roots of anarchy in The Book of Mormon and church teachings come in many forms and manifestations. Decentralized power is one the church still employs to this day, with its lay clergy and Mormon wards that bestow non-permanent callings of authority for ground-level operations of the church on people in the ward. Joseph Smith said, “I teach them correct principles, and they govern themselves,” a mantra for many LDS anarchists who hearken to the idea of acting on principles rather than allegiance to authority.

Van Wagenen likes the story of the prophet Abinadi in The Book of Mormon who criticized the wicked King Noah for his cruel taxing of his people and corrupt regime. Abinadi was burned alive by Noah, but his bravery inspired a member of Noah’s court, Alma, to convert to Christianity and lead a group of followers from the kingdom and into the wilderness. His followers wanted Alma as their king, but Alma was not fond of crowns.

“He basically said that if you can always have someone righteous as king, that would be great. But since that’s not always the case, you shouldn’t make me your king, and you shouldn’t make anyone your king,” Van Wagenen says. This political equality, he says, goes hand in hand with economic equality that was enacted early in church history with Joseph Smith’s collectivist United Order program. And, in Utah’s early history, Van Wagenen points out, Brigham Young allotted land as needed by the saints, and that the territory held water, minerals and other resources under public ownership—all in living with gospel principles.

You May Be a Mormon Anarchist If …

You like the sound of: “And they had all things common among them; therefore there were not rich and poor, bond and free, but they were all made free, and partakers of the heavenly gift.” (4 Nephi Verse 3)

Van Wagenen understands that people could interpret scriptures how they want, but if 4 Nephi from The Book of Mormon speaks to you, it may be because you’ve got the itch for anarchy.

“People say you can find whatever you want in scriptures, and that’s right—but only to some degree. There are things that are just there,” Van Wagenen says. “In The Book of Mormon, it clearly says that people had all things in common, there were no rich and no poor and that was the most righteous the people ever were. And when they became wicked, they had a society divided up into classes.”

Mo’ Feminists Still

Making Waves

For Tresa Edmunds, a self-described Mormon feminist and founder of Women Advocating for Voice and Equality (WAVE), being a Mormon feminist is more about speaking up for LDS women than it is about speaking out against the church’s patriarchy.

“We sustain our leaders,” Edmunds says. “We just want to contribute to the kingdom by offering our voice, our talents and our experience—and leave the big revelations up to the prophets.”

WAVE operates mainly as a think tank for LDS women who want to learn more about the role female members have had in the church and what day-to-day impact a pronounced female voice can have in the church. Unlike some Mormon feminists, WAVE does not agitate for women to receive the priesthood authority, which is reserved for male members. Rather, her organization takes a more diplomatic and grass-roots approach to remind the brothers and elders of the church that the sisters should have a say in basic issues, as well.

“I really do believe [church leadership] are doing God’s work,” Edmunds says. “But we have to serve each other, and I also believe that God isn’t going to send an angel to Thomas S. Monson [when] he can just ask his wife what she feels about something.”

Since the group’s launch in 2010, it’s completed Words of Wisdom, a quote book that’s a compilation of sayings from female leaders in the church that can be downloaded for free from the group’s Website. WAVE’s next project, Edmunds says, is to create another quote book of the church’s references to Heavenly Mother, a female deity often discussed in the 1800s and early 1900s.

For Edmunds, a Mormon feminist is not so controversial.

“Feminism is the belief that men and women are equal. From a Mormon perspective, what that means to me is that each of us should be allowed equal access to develop our talents,” Edmunds says, “and, especially from a Mormon perspective, to contribute to the kingdom.”

You May Be a Mormon Feminist If…

You’ve ever said, “I’m not a feminist, but …”

To Edmunds, that phrase is a pretty big indicator: “You’re a feminist! Just embrace it!” Edmunds understands that labels can get in the way of discourse and action, and says that a Mormon feminist understands that men and women should not be confined to gender roles, but rather valued for their contributions. She points out how the stay-at-home dads she knows feel stigmatized for not being the breadwinner in the family, even though they’re better suited to stay with the family.

“What difference does it make?” Edmunds asks. “If someone is nurturing in the family, why does it automatically have to be the woman?”