Medical misfortune didn’t turn Jean-Dominique Bauby (Mathieu Amalric) into a saint. Just emerged from a two-week coma—the distraught mother of his children, Celine (Emmanuelle Seigner), only recently gone from his bedside at a hospital near Calais—the editor of French Elle still ogles the boobs of the woman who leans over him. In his head, he’s cocky, horny and vital.

In the real world, however, Bauby has been almost completely paralyzed by a severe stroke: his face twisted into a perpetual frown, only his left eyelid capable of any motion whatsoever, his thoughts known to us only through voice-over. But it’s nearly 40 minutes before we actually see that side of Bauby, thanks to director Julian Schnabel’s decision to shoot almost the entire first third of the film from Bauby’s point of view. We understand the devastating nature of his diagnosis—the rare “locked-in syndrome”—from a doctor’s description, but Bauby himself isn’t permitted to become an object of pity. Before we’re allowed to grasp the full extent of what has happened to his body, The Diving Bell and the Butterfly forces us to know him from his still engaged mind—even if that means introducing us to all the ways in which he’s still kind of an asshole.

Adapted from Bauby’s autobiography, The Diving Bell and the Butterfly eventually addresses the complex communication system that allowed Bauby to “dictate” to his secretary Claude (Anne Consigny), one letter at a time, through individual blinked indications on an alphabet board. As remarkable as the accomplishment may have been, however, it would be a mistake to reduce the story to the mechanics of the autobiography’s creation. Schnabel and screenwriter Ronald Harwood are interested in what happens to a man forced to live entirely in his head. And while the opening point-of-view device does allow Schnabel to mess with viewers by making them up-close-and-squeamish stand-ins when Bauby’s dead right eye is sutured shut, it’s not just an artsy gimmick. It’s a construction that allows a warts-and-all understanding of Bauby’s personality to emerge so brilliantly.

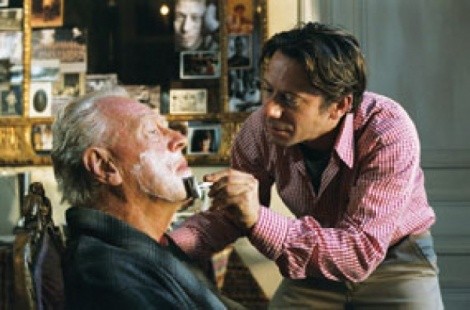

Unsurprisingly, much of what emerges from Bauby’s mind is either remembrance of earlier times or elaborate fantasies. Flashback sequences show Bauby visiting with his housebound elderly father (Max von Sydow), enjoying an outing with his mistress (Marina Hands), riding in a convertible—eventually, even the moment of his stroke. Amalric easily might have overplayed Bauby’s joie de vivre in an effort to make his paralysis seem even more tragic, but instead he maintains a simple twinkle in his eye to indicate the life force within him, still driving him to imagine post-stroke possibilities like an oyster-slurping dinner date with Claude.

The real triumph of The Diving Bell and the Butterfly is that it almost never resorts to triumph-of-the-human-spirit platitudes, even abruptly cutting off one of the few moments of sentimental music. Schnabel and Harwood don’t avoid the indignities of Bauby’s life entirely—the inability to deal with a fly crawling on his nose, or watching his children play on the beach without him—but they find the human interactions more compelling. If there’s tragedy in the scene where Bauby’s father attempts to communicate with him over the phone, it’s not so much in Bauby’s frustration. It’s in the pain of a father—beautifully, hauntingly played by von Sydow—for whom his distant, silent son might as well be dead already.

Stories of people with both disabilities and character flaws aren’t anything new, but most of them exhibit their protagonists’ surliness and/or bitterness only so that they overcome these terrible attitudes and make peace with their new lives. The Diving Bell and the Butterfly doesn’t go there; Bauby remains the kind of person who leaves Celine in the uncomfortable position of serving as his translator for a phone conversation with his mistress. His autobiography stands as an astonishing example of determination, it’s true, but the film version isn’t about to place him on a pedestal for his efforts. From the first moment to the last, it remains a testament to someone whose ordeal didn’t change him. We’re allowed to watch a man whose tragedy didn’t change his singular internal self—even the parts of that singular, internal self that leer at the nearest boobs.

THE DIVING BELL AND THE BUTTERFLY

![]()

Mathieu Amalric, Anne Consigny, Marie-Josée Croze

Rated R