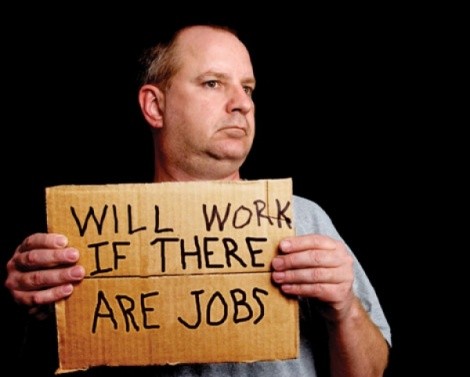

“We’re looking at alternatives other than criminalizing people for being homeless,” says Bill Tibbits, Anti-Hunger Advocacy Project coordinator for the Crossroads Urban Center. Instead of a punitive panhandling ordinance, Tibbits is pushing Salt Lake City to follow the lead of other cities that have created transitional job programs. “In places that have done this, the businesses have often seen a noticeable reduction in panhandling,” he says. While everyone agrees jobs for the jobless can only improve local lives and the local economy, the biggest challenge will be to convince city government that it needs to take part—and to what degree.

Tibbits says there are many resources for job-skills training, but members of the homeless population who have not held a steady job for multiple years because of a lack of skills, criminal pasts or substance-abuse problems need more than a workshop on how to write a résumé. “There is a need for a specific transitional jobs programs for people that need that first step back into the workforce.”

If the city could create temporary positions—three to six months long—it would give the workers experience to carry into the job market.

“We’re not asking the city to employ 10,000 people,” he says. Instead, the program might employ only 10 to 20 people. “Ideally, for the people who this works for, after a couple months you have a different set of 10 to 20 people.”

The jobs could be tasks like cleaning or street maintenance, an ideal way to create jobs that move people from the streets to self-sufficiency. “Salt Lake City is such a progressive city, it’s time for us to lead in this area and do something in terms of homeless policy that has never been done before in Utah,” Tibbits says

But for Salt Lake City Council chair J.T. Martin, that’s not city government’s strong suit. “Government’s not good at that kind of stuff, government’s good at supporting from the sidelines,” Martin says. He points out that Salt Lake City and the state already have a large network of nonprofit agencies and other entities that provide job-training services for the state’s low-income and homeless. There’s also Deseret Industries, the thrift chain owned by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, which provides work experience to people receiving state assistance, refugees and recovering substance abusers. Martin says he certainly doesn’t oppose a job program but just wonders why the city has to set it up.

“I have to ask the question: Isn’t that a wonderful thing that the Crossroads Urban Center should be providing?” Still, Martin says, because the idea is new, the city wouldn’t be opposed to studying it.

There are various models of transitional-job programs across the nation that have involved city government to varying degrees. The successful Chrysalis program in downtown Los Angeles operates a shelter and homeless distribution center that stepped up its services in 1993 by creating two companies that employ clients who come through their job-search counseling services. Chrysalis Works, a street-maintenance business, actually provides more than half of the entire nonprofit’s yearly revenue. The company provides trash pickup, weed abatement, graffiti removal and other services. The work is largely manual labor, but Michael Graff-Weisner, Chrysalis’ vice president of government relations, says it’s not technical job skills that participants get out of the program.

“We do learn ‘hard’ skills—operating equipment and machinery—but probably the biggest thing our clients are learning are work habits,” Graff-Weisner says, speaking of what his organization calls “soft skills.”

“Showing up on time, in uniform, ready to work with a good attitude, being reliable,” he says. “A lot of employers hire for those things other than ‘hard’ skills.”

All the employees are paid minimum wage and compete for contracts in Los Angeles’ Business Improvement Districts. Chrysalis Enterprises, the organization’s other business, is a temporary-staffing agency that draws from the nonprofit’s pool of people in its job-training courses and refers them to temporary positions, which can lead to full-time positions. Chrysalis’ transitional jobs provide temporary jobs to 600 individuals a year, and have provided jobs to more than 10,000 homeless and low-income residents.

“These jobs are not meant to be a permanent stop,” Graff-Weisner says. “It’s meant to be a launching pad back into the workforce.”

While the skid-row homeless population of Los Angeles and Salt Lake City’s homeless do not necessarily compare well, the Streets Team initiative launched in Palo Alto, Calif., in 2004, is a similar venture but on a smaller scale. As in Salt Lake City, business owners in Palo Alto were concerned about a sudden increase in panhandling. They also, according to a survey, were concerned about blight and urban decay. The job-creation program became a collaboration between the Palo Alto City Council, business leaders, law enforcement and local nonprofits to solve both problems.

“It seemed like a unique solution to both problems: pretty cheap labor to clean and maintain the downtown area and give people a second shot,” says Chris Richardson, program manager of the Downtown Streets Team nonprofit. The initiative now puts homeless individuals to work cleaning streets, trimming trees, providing janitorial services and drawing chalk lines at city soccer fields.

“The core idea is to get people up and running with a small job like cleaning the streets—they become invested in the community and can reintegrate into the community,” Richardson says. The Downtown Streets Team program is also unique in that it doesn’t pay its participants a cash wage. Participants are compensated with food and housing vouchers or, in some levels of the program, gift cards to retail stores such as Walmart. Richardson says the program currently offers 42 positions in Palo Alto and 36 in two other locations in the county and recently franchised to Daytona Beach, Fla. Since its inception, the program has offered work experience to more than a thousand homeless people, 151 of whom have completely transitioned to permanent jobs and housing.

“One lady on a team was out of work for 25 years, addicted to drugs for 24 years, until she got with us,” Richardson says. “She’s three years sober and works full time now.”

For Tibbits, these success stories are exactly the kind of collaborative solutions he wishes Salt Lake City would have prioritized instead of deciding to simply get tough on panhandlers.

“If the city is really serious about doing something about the number of panhandlers, then it needs to create a jobs program for people who can work,” Tibbits says.

|

Eric

S. Peterson:

|