Bateman’s newest exhibit at Phillips Gallery, Mechanical Brides of the Uncanny, takes the technology to look at a vision of the future from the 1800s, when the camera first came into widespread use. Several years ago, he became fascinated with tintypes, a kind of early photograph on metal plates—something like the Polaroids of their day, in that they developed quickly and were relatively inexpensive. By the late 1800s, the card de visite (literally “visiting card,” or calling card) proliferated with images of everyone from generals and heads of state to common people. Today, they are widely collected.

But, like everything in his work, Bateman filtered the tintypes through the lens of his own imagination, manipulating characters in them to become robots—or, more properly, “automatons,” he notes, since the term “robot” didn’t exist in the 1800s. This exhibition combines a set of 20 framed tintypes and sets of cards including all the images from his tintypes, plus seven of his larger color prints.

Bateman has used tintypes before in his larger prints, and notes that, every time he used vintage photos as subject matter in his art, he treated them as objects. The next step was to create the objects themselves. “One of my mentors taught me you can’t just do one of anything; you have to make at least three to learn about them,” he jokes. “I kept going until I hit 21.”

It’s a collection reflecting the personality of the age, with a jaunty metal man in cowboy gear, solemn-visaged human wife with automaton husband, several machine nannies with children in tow. A female robot wears a metal hairdo and hoop skirt. It’s hard to tell who is subservient to whom in some of them: A Civil War-era officer comports with a robot: secret weapon or supreme commander? They all affect serious poses, not a grin among them, but some more loose than others, as though secure in some hidden knowledge or power.

“I had to come up with a rationalization for placing robots in the 1800s, and it was the comparison of robots with cameras,” Bateman explains. “Humans had looked at objects for centuries, but the camera was the first time an object looked back at us.” The visual effect of these monochromatic images is a little discomforting, and, Bateman spoofs in his artist’s statement, “They were widely documented, although few examples remain today.”

In the 1800s, the backs of photos had ingenious inscriptions. His card series makes humorous use of them, replacing historical sites like London Photography Studios with his own name. There’s something incongruous about seeing a Website on the back of a vintage-looking card. The faux-antique brown metal tin makes the set a nifty artifact.

His larger prints could make up—and have made up in the past—an entire show on their own, such is the arresting power of their images like wakeful dreams. This is a new series of them, incorporating images from tintypes within them, hanging from a tree or on a raft floating down a river. Rather than surreal, they combine very real objects in unusual combinations to create metaphorical impact.

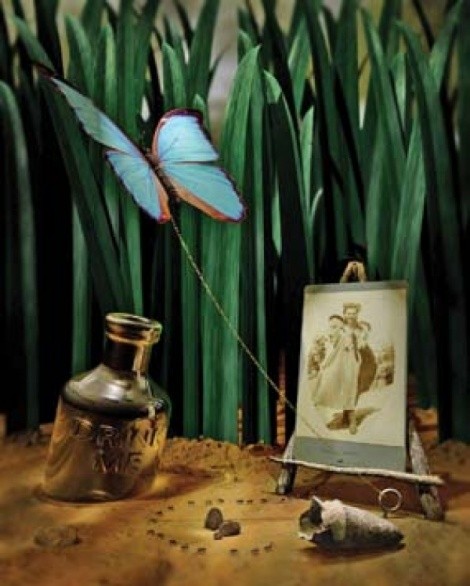

“Transformation,” pictured, mirrors a butterfly in the tintype with a live butterfly chained to the ground. “Attraction” repeats its motif with the moon above a water glass with a boat weathering its shifting tide, two magnets at a distance, and a boy and girl, gazing at each other from the expanse of the separate tintypes in which they dwell. “Cupid and Psyche” takes the classical myth of the two lovers separated, with tintype girl waiting in repose while her lover departs on archaic flying machine, three nails in the ground for the three tasks she has to complete to win him back.

The 3-D rendering software Bateman uses is similar to that used in Hollywood, creating textures like silver or glass. Almost every surface seems to contain or reflect other objects, as the bottle marked “drink me” in “Transformation” reflects an image of the woman and butterfly in the tintype. These pieces reward examination with incredible depth of detail, even to the artist. “I feel like I’ve done something right if, at the end of the day,” he says, “I’ve discovered something new.”

Mechanical Brides of the Uncanny: Edward Bateman

Phillips Gallery

444 E. 200 South

801-364-8284

Through March 13