Page 3 of 3

CW: On your Website, you mention the reaction you had to a college professor’s quote that “the first great Mormon writer will be excommunicated from the Church.” Without putting you in the position of claiming to be that “first great Mormon writer,” were you thinking, even if you hadn’t had this personal epiphany, there would come a moment where you would collide with this wall so hard that something would have to give?RD: Oh, yeah, I absolutely knew that was coming. I think that’s why that professor’s statement really resonated with me. … I just knew that as a filmmaker, if I was always stuck in an area where I never said fuck or goddamn, and you never see a naked woman, and nothing ever gets too violent, that that would not be beneficial to me as a filmmaker. I’d need to go out and find out what for me, personally, was right and wrong. … So what I found in filmmaking is that these things that were taboos, I don’t have any problem with [them]. … Filming these scenes did not feel in any way like committing sins.

I always knew, though, that when it came down to it, I wouldn’t be able to sit at a table with 12 men and have those 12 men say, “Stop making these kinds of films.” I would just say, “I appreciate your point of view and your sincerity, and now I’m going my own way.” … Right after Brigham City and States of Grace, I still had people coming up to me and saying, “It’s so nice that you’re making family films.” And I always felt frustrated, because it was like, “Are you not paying attention?”

CW: Does it feel now like you’re making films that are not religious enough for the religious audience but too religious for the Sundance audience, which seems kind of like Falling’s natural fit?

RD: Falling was, from its very inception, you know, I am not making this for any market. … And in the process, whenever there was a decision to make, … whether it was casting a certain person, or doing this or not doing this, I would always just say, “OK, that’s the commercial decision and this is the not-commercial decision, and I’ll make the not-commercial decision.” In a way, it’s something of an experiment for me, because who makes a film that every step along the way—everybody makes the opposite decision: “Whatever’s commercial, OK, that’s what we do.” For this one, I thought, “What’s commercial? OK, let’s do something else.”

And I have no illusions that this film is going to be a Titanic at the box office. I would like it to be a small success, but that’s kind of my experiment. If filmmakers make this kind of film, where they’re not catering to audience demands or market demands in any way, will you make something that’s so unique that it will actually draw people?

CW: You’ve submitted previous films to Sundance, unsuccessfully. Does it feel to you like maybe this one is the one?

RD: I would sure hope so, because if this isn’t it, … [laughs]. After the [Sunstone] screening, some of the comments I got were like, “You know, you’ll have better luck if you take out some of that Christus stuff at the end; you’ll get into the festivals.” And it’s like, festivals are just one more market, if you look at it that way. I’m not going to say, “Here’s the film, and it’s just as I want it,” but, if I take out something that I think is a vitally important part of it just to satisfy some festival programmers … well, screw that. I became very aware since God’s Army came out of the critical resistance—and audience resistance—to films not just with religious content, but with spiritual content. But I can’t change what I’m doing to satisfy that.

Right now, … for me, there are two kinds of films I’m making. One type is just purely commercial films, and the other type is very personal films. And I don’t want to pollute one or the other. … Now if you look at someone like [independent filmmaking pioneer John] Cassavetes, he would say, “Well, it’s impossible, you’re not going to be able to do it. You’ll get hooked on the Hollywood tit, and you’ll never be able to leave.” … And I hope that he’s wrong because, personally, I don’t see how to do those other films unless you’re either independently wealthy—which I’m not—or you finance it through doing something more commercial. That’s what he said, but I don’t know if he really believed that because, near the end of his life … as an actor, he could go out and do whatever garbage they’d give him a check for, and then he would take that money and go make a film with it.

CW: So does Provo, Utah, still feel like the right place for you?

RD: Yeah, it does, actually. I spent 10 years [in Los Angeles] and going back now holds no appeal. The culture there is so removed from the act and art of making films that I never want to be a part of it. The things that dominate your life down there have nothing to do with making films. And, for some reason, there’s a culture of assholery—why are these people all rude, mean, unhappy people?

I came back [to Utah], I think, in my ninth year of living in L.A…. trying to raise money. Late at night I stepped out on the street; the stars were really bright that night, and I could see the mountains, and the air was clean. And it was so heartbreakingly beautiful after almost 10 years of smog and just … L.A. that I knew if I didn’t live here, I’d have to live somewhere that you could wake up in the morning and see a mountain, have a nice quality of life. And … with seven kids now, L.A. is not an option.

It’s interesting to me in looking at what I’m building here. It started off with me as an actor … realizing if I wanted to do something interesting, I’d probably have to write it myself. Then, eventually … even though people liked my scripts, nobody was making them, so I realized I’d have to produce them myself. And if I’m producing, I’m sure as hell going to direct. … And then, if you want to stay in the business, you’ve got to have a lot of control of the distribution, so I formed the distribution side of it. It’s been a natural evolution and yet very necessary. I can’t see now trying to make a living just as a writer, or just as an actor, or just as a director. It’s, like, virtually impossible. At least for me, because I’m not a 19-year-old, hot, young girl, I’ve got to actually create the whole thing. I’m not high in demand in the marketplace.

After creating all these relationships with exhibitors, now I am finally really in a place that, as long as I have the marketing dollars to back it up, I could open on 1,500 screens. And that would be kinda fun—just to sneak in and take the weekend away from all the big boys in Hollywood. I think Evil Angel’s got a good shot at it. It’s fun. And there’s another film we’re putting together now to shoot next spring, and I think that’s even more commercial. So, Main Street, I don’t intend for it to be just kind of a boutique, small thing. I want to come in and play in the majors.

Richard Dutcher Filmography

A brief look at Dutcher’s films, with his own observations on them.

(1997)

Dutcher wrote his first role for himself in this romantic comedy, playing a womanizer who needs to learn to settle down and be faithful. “Better than any graduate school in the world, Girl Crazy taught me more about filmmaking than I could have learned anywhere.”

(2000)

In the feature that made his name, Dutcher played a cancer-stricken missionary in Los Angeles serving as mentor to a new arrival (Matthew A. Brown). “I put everything on the line for this film. I was absolutely sure it would work.”

(2001)

Dutcher ventures into murder mystery, playing a small-town Utah sheriff investigating a series of killings. “From conception to premiere, it took less than nine months. My fastest film.”

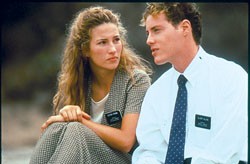

(2005)

Marketed locally as God’s Army 2, this stand-alone follow-up dealt with the intersecting lives of Southern California missionaries and those they attempt to serve. “Said everything I wanted to say about religion ... at that point in my life.”

(expected 2008)

An aspiring filmmaker and his aspiring-actress wife face moral choices that will change their lives. “Making it almost broke me physically, mentally and spiritually. It has become my favorite film.”

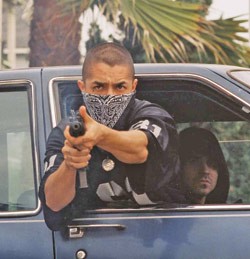

(expected 2008)

Dutcher cast Ving Rhames (Pulp Fiction) in a supernatural thriller he describes as based on the Lilith myth. “States of Grace was my Christmas movie. This is my Halloween movie. Guns, blood, demons and just a little theology.”

cw