Page 2 of 3

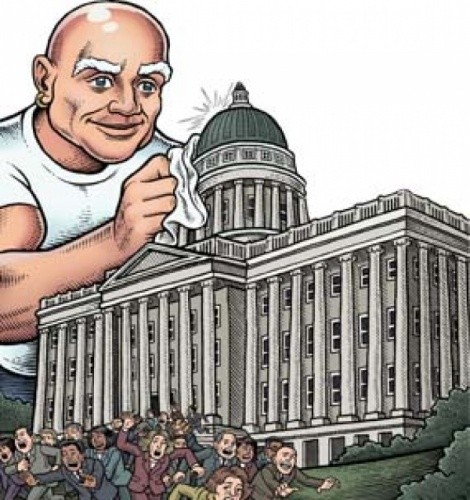

The “religion” of ethicsnNewly elected House Speaker David Clark, R-Santa Clara, sounds like a man serious about ethics reform. The perception that Capitol Hill needs a good scrubbing was at the top of voters’ minds during the 2008 campaign, he notes. “I hope that all of my colleagues’ memories will, even after the election, still be crystal clear,” he says.

Already Clark has asked the seldom-used House Ethics Committee to hold regular meetings and pledged that discussions of changing the ethics-complaint process will be vetted by the group, which is the only committee in the Legislature with an equal number of Democrats and Republicans. “That’s my attempt to say this is really a bipartisan, fair approach,” he says.

| The Players |

n Has put ethics reform on the fast track in Utah's House |

n |

|

Before the legislative session even began, Clark’s leadership team negotiated with Senate leaders about what the Senate, which has blocked previous years' ethics reform packages, would accept. The agreed-on package of bills calls for a ban on expensive entertainment gifts to lawmakers, lowering the threshold cost of meals lawmakers can secretly accept on lobbyists’ dimes, a one-year “cooling off” period before retired legislators can enter the “revolving door” of lobbying, quicker reporting of campaign donations and a ban on lawmakers' pocketing of campaign cash for personal use. Clark says the idea is to get the low-hanging fruit out of the way early, but he also pledges to work with Democrats on broader ethics reforms through the session. He doubts an overhaul of the ethics complaint process can be ready by the end of the 2009 legislative session but promises new rules by summer.

Clark was subpoenaed three times to testify during this summer’s secret meetings of the House Ethics Committee. His Democratic counterpart, Minority Leader David Litvack, D-Salt Lake City, served on the committee that sat in judgment of two lawmakers. Both men came away feeling the process failed. One main problem: The House's Code of Official Conduct is so vague the committee couldn’t say for sure what was ethical.

The committee had trouble with the question, “Was some of the behavior unethical, or merely unbecoming?” Litvack says. Clark wants to establish some sort of ethics training for lawmakers. Litvack doesn’t think it’s possible to draft a document spelling out right and wrong behavior but says an ongoing ethics conversation should be valuable, particularly since many of the Legislature’s 104 members are new each year.

Litvack’s Democrats will be pushing for creation of an independent commission to hear future complaints about lawmakers. He says this summer’s ethics committee investigations instantly devolved into politics. The ethics complaint-review process “needs to be the closest to religion that we get in politics. It needs to be that pure. It didn’t always feel that way.”

The House Ethics Committee met twice this summer and fall. The first meeting took less than 15 minutes and was shut down after former Republican Rep. Mark Walker, the subject of the probe, resigned his seat. The second meeting—over bribery and abuse of power allegations brought against Rep. Greg Hughes, R-Draper—was seven days of secret interviews of lobbyists and legislators. In the end, the committee decided not to pursue any of the charges. Members did, however, write a letter admonishing Hughes for “unbecoming” conduct.

The committee also recommended future training in ethics for lawmakers.

Don’t need no stinkin’ ethics class

nRiesen says he doesn’t question the motives of those talking about ethics training, but doesn’t buy it. “Even being next-to-a-freshman legislator, I know what I can and can’t do,” says Riesen, who was elected to a second term in November 2008. “I don’t need a code of ethics. I don’t need to go to a class to have somebody tell me what is inappropriate behavior for a sitting member of the Legislature. It’s common sense. You don’t use your office for private gain. You don’t use undue influence of your office to extort or intimidate other people.

“When you offer a bribe to a sitting member of the Legislature to change a vote, or when you attempt to extort money from registered lobbyists to promulgate your point of view, or to threaten their potential legislation, that’s not the way you run the people’s House, I’m sorry.”

The two legislative bribery allegations that tore the Legislature apart had origins in the 2006 school-voucher fight. Several gathered in Irvine’s office were veterans of the antivoucher campaign. Rep. Sheryl Allen, R-Bountiful, who heads up the House’s moderate Reagan Caucus and brought ethics complaints to the attention of House leadership, is on the executive committee of directors of antivoucher Utahns for Public Schools (Allen also works for the Davis School District Foundation). Irvine was one of the antivoucher group’s lawyers.

During the voucher campaign, public-school advocates felt they’d been steamrolled by pro-voucher lawmakers using bullying tactics and wads of out-of-state cash to barter for votes. Public-school advocates came away feeling something was seriously wrong with democracy in Utah.

As the campaign to have the 2006 law overturned slogged on, they heard more complaints, including allegations that attempts by moderate antivoucher Republicans to run in primaries against conservative incumbents were met with threats to the candidates’ jobs or to the Capitol Hill interests of their public-school employers. Several who felt they had been victims of such tactics agreed to put their complaints in writing.

The two 2008 ethics committee hearings didn’t do much to resolve complaints, but they appear to have set the price of a lawmaker in Utah: $50,000—give or take a few thousand—the amount allegedly offered in both cases.