nThe call for help came from Envirocare, the radioactive waste repository now known as EnergySolutions. Four pelicans had landed on one of its low-level radioactive ponds in Tooele County. Three of the birds thought better of the decision and flew off. But one remained—for days. n

Envirocare workers traipsed out to the pond with their equipment, and sure enough, they found one hot avian. They scooped up the bird and took it to one of their decontamination baths. Then they called Candy Carlson. n

In her professional life, Carlson is a real-estate agent. But the bird world knows her as Utah’s premier migratory-bird rehabilitator. At least she was. n

Carlson has fallen victim of what appears to be a bureaucratic brain cramp amid an ambitious if critical rebuilding campaign on the part of Tracy Aviary, which severed ties with her and another rehabber earlier this year. n

But, for more than a decade, Carlson has definitely been the go-to person for bird rehab. People would discover injured birds and call Tracy Aviary, but because of a unique and longstanding collaboration with Carlson, the aviary would refer people to her. The aviary, after all, is a park, not a sanctuary or clinic. Its Website calls it “America’s oldest and largest bird park, founded with a private bird collection.” n

That day five years ago when Carlson got the call from Envirocare, she jumped in her Subaru wagon and drove out to Utah’s west desert to a designated drop, off an Interstate 80 exit, between the road and the ponds. Carlson had already called her veterinarian, who advised giving the pelican fluids and antibiotics. n

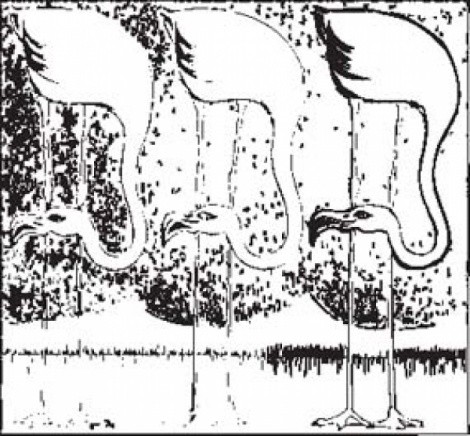

“The white pelicans come here to breed on remote spots on the Great Salt Lake. Often, it is the young ones that incur injury as they don’t have the flight experience to maneuver around power lines, etc.,” she says. “I took him home early in the evening and stayed up with him until 4 in the morning when he went into cardiac arrest and died.” n

Carlson and fellow rehabber Tazia Vickrey try not to obsess over the problems they see every day. They are consummate believers in making a difference, one bird at a time. n

“What we do probably affects people more than it affects birds,” Carlson says. “We’re not going to keep a bird from going extinct; there are bigger things out there that we have no control over.” n

Radioactive ponds, for instance—and traffic, pesticides, tree removal, high-rise buildings and high-voltage power lines. “Over the years, I have dealt with pelicans that have been electrocuted, that dropped out of the sky onto west-side freeways, that fell through canopies in Sugar House shopping strips while people were getting their hair cut, that landed in people’s swimming pools, or that were just discovered down in an isolated spot after suffering an impact injury,” Carlson says. “I have placed five non-releasable pelicans with Tracy Aviary on educational permits, one with Hogle Zoo, lost two (from radiation and electrocution) and released the rest—about a dozen.” n

When aviary director Tim Brown talks about birds, he likes to paraphrase from Richard Louv’s book, Last Child in the Woods. It’s about how important it is for children to connect with nature. In an increasingly urban society, we are bringing up a generation of children removed from the natural world, unexposed to the cycles of life. Unless, of course, seeing The Lion King counts as exposure. n

Brown became director of the aviary in 2005 as the park was spiraling almost imperceptibly downward. For most people, the eight-acre parcel perched at the southwest corner of Salt Lake City’s Liberty Park had simply always been there. They knew it was a little run down and its exhibits a bit remote, but visitors had come to expect that. And besides, the aviary was about to open Destination Argentina!, its first new exhibit in 20 years. Good news. n

Then bad news came. In 2006, the American Zoological Association pulled the aviary’s accreditation. The park was guilty of “substandard facilities … deferred maintenance … and insufficient past and uncertain future funding,” the AZA noted. The association also wanted to see evidence of progress. n

Brown and other supporters of the aviary are focused on reaching that progress through a Nov. 4 bond issue. They see the vote as crucial to the aviary’s survival. But it is Brown’s current frustration that bird rehabilitation is somehow reframing the campaign. n

The bond issuance would be enough for the aviary to meet AZA standards. The park would get $13.5 million immediately and another $5 million after it raises $1.5 million privately. The aviary recently secured a $750,000 anonymous donation—half of the amount it must raise in order to qualify for the bond money. But the bird rehab question has become a public-relations nightmare, which Brown is desperate to resolve. n

It was never supposed to be a big issue. However ill advised, the decision to get rid of the volunteer rehab program became entrenched. And, because of the void it left in the county, Brown is now dealing with two problems he never anticipated—the broken rehab effort and the lost accreditation. n

“I didn’t see it coming, to some extent,” Brown says of the accreditation dilemma. “They hired a local committed to Salt Lake City and … never did I look at Curious George and the Man in the Yellow Hat and say, ‘I want to be a zookeeper.’”

nn

From fledgling to full-grown

nNo, Brown is not your average zoo guy—nor is he a bird person. After three years of river running, ski-bumming and working with the state Division of Wildlife Resources, he got a degree in wildlife biology from the University of Vermont. He was working as a river guide and participating in fishery research on southern Utah rivers when, he says, he had an epiphany about the potential of environmental education. n

Graduate work at the University of Utah led him to the directorship of the Utah Society for Environmental Education. In 2002, he moved on, having earned a graduate degree form Antioch University-Seattle. He was working at the Center for Green Space Design in Salt Lake City just before signing on with the aviary. n

The aviary board was looking for someone to move the facility forward, since it had been stuck in neutral for so long. The aviary opened to the public in 1938, after the donation of 200 birds from the private collection of Salt Lake City banker Russell Lord Tracy. Calvin R. Wilson grew the aviary, where he served a 37-year tenure as curator until 1975. n

Aviary management actually merged with that of Hogle Zoo for a time in the mid ’70s, but the aviary was always the poor stepsister and never made a dime. Then-Mayor Ted Wilson wrested back control, and for a dozen years, the aviary was managed by Salt Lake City Corporation. n

The city threw about $500,000 at infrastructure needs over the years—enough to keep the aviary’s head above water. Then, in 1993, the Friends of Tracy Aviary formed in response to then-Mayor Deedee Corradini’s call to outsource city functions. Within a year, the aviary was flying solo with a largely advisory board trying to raise funds with fairly dismal results. Good will and funding from the Zoo, Arts and Parks tax initiative helped shore it up. n

When Pete Taylor joined the board some six years ago, fund-raising was still the main issue. The aviary was being run by Sharon Stenz, whose organizational skills had been honed at the Girl Scouts of America. n

But the early 2000s weren’t the best of economic times, and when Stenz was hit by a car and seriously injured, fund-raising took a nose dive. “The board was loosely run at that time frame, and looking forward, we didn’t know the long-term prognosis for Sharon,” says Taylor, a professional headhunter who became board chairman. “The budget was askew, cash flow was extremely tight and a group of board and staff, on a bare-bones budget, started to work through this.” n

Part of the working through required finding a new director. “Tim had the best foundation with the mission of the organization and his ability to tie and get into fund-raising,” Taylor says. “He had to deal with a lot of setbacks not of his doing—30 years of past ignoring the organization. He put together a strong format to rebuild and in the last five years, around $4- to $5 million has been spent on upgrading the aviary.” n

Indeed, Brown has brought a vision to the aviary. After Destination Argentina! came the exhibit Kennecott Wetland Immersion Experience. Brown’s wife, Angela Dean, an architect, has donated her time to secure materials that finished the Chase Mill, the aviary’s only public indoor space. n

The master plan calls for a “periphery experience,” by which visitors will go from exhibit to exhibit and see the birds through viewer-friendly barriers. Things seemed to be moving along—until the accreditation setback. n

No one associated with the aviary anticipated the denial. The AZA had even provided a mentor to Brown who “led him to believe it was very positive,” Taylor says. “We were surprised when they denied our accreditation, but the things they wrote up weren’t a surprise. The infrastructure is what it is.” n

And so, it has become even more important for the aviary to win its bond election. Earlier this year, the Salt Lake County Council approved putting the $19.3 million bond proposal on the ballot. Proponents say the measure would raise property taxes on a $235,000 home by $2.51 annually for 15 years. Voters will also weigh in on a separate $65 million bond proposal for updates to the zoo.n

Broken bird patrol

nWhen Brown joined the Aviary, bird rehabilitation was a staple. For many years, rehabilitation had been done on-site. Rehabilitation is both a labor of love and a federally sanctioned activity because essentially all native birds are, in fact, federally protected. n

With 5,000 species of birds worldwide, there are some 1,000 species native to North America. Since 1918, the Migratory Bird Treaty Act has made it “unlawful to pursue, hunt, take, capture, kill or sell birds” listed as native to the United States. The idea back then was to stop commercial trade in birds and their feathers, which, according to the law, “had wreaked havoc on the populations of many native bird species.” Eggs and nests are also protected. n

Only a few birds, like prolific starlings and pigeons, are off the list. But even handling the humble and plentiful sparrow requires a permit. n

Brown notes that 5 million to 7 million birds use the Great Salt Lake as a stopover every year. Many of them—like the American white pelican—are actually native to Utah, and their flight paths are exhibited at the aviary. n

Candy Carlson started out as a docent at Hogle Zoo doing education outreach to schools and began working with avian rehab, mostly with birds of prey and songbirds. She moved to the aviary and worked there until the early '90s, when work hours, costs, quarantines and space issues forced the rehab functions off-site. n

The aviary, however, continued to carry the state and federal permits for the rehabbers. After all, it had to field many calls for help from the community. n

The rehabilitation community was admittedly a little loose, with four or five willing rehabbers at the most. In the summer, there was more need, and the aviary would try to pick up interested people and offer classes in rehabilitation. Carlson started teaching classes in her home. It was nothing if not a demanding avocation. n

“It’s 24/7,” Carson says. “When you go through the baby-bird season, you have no life. My phone rings (all day) with people who find a bird and don’t know what to do.” n

Many would-be rehabbers quit once they realized the mess and the dedication required. “Some things can be sad and disheartening, but a few successes are so amazing,” Carlson says. When Vickrey came along, there seemed to be some stability. She started out volunteering at the aviary and then worked in the ticket booth. In the beginning, she rehabbed starlings because they weren’t protected. n

“Tazia was extremely dedicated and committed, and another woman, Kathryn Alf, wanted to do ducklings and waterfowl—for the last half-dozen years it was the three of us doing hundreds and hundreds of birds a year at our expense,” Carlson says. n

They paid for veterinary services, and for food and transportation, although the Aviary often donated mice. Carlson calculates she spent more than $13,000 from her own pocket; Vickrey about $2,000. And then there was the time spent documenting the bird injuries and fatalities, page after page: n

Townsend’s solitaire—neurological head tilt, probable impact—died during night n

Interior Gray crowned Ropsy-finch—fix right humerus, possible coracoid tiny puncture, possible cat—died n

Goldfinch lesser—found not flying in yard, probable coracoid—released n

Magpie—found in garage, possibly brought in by cats—died n

Great horned owl—building strike, head trauma & injury to right eye—delivered to … n

Male mallard—hit by car, left foot and leg hit, left eye closed—released with slight limp n

n

Late last year, Carlson began to prepare to renew her state permit through the aviary. At first, she was told she’d need to get a master rehabilitation certification—something not offered or required in Utah. Last December 4, Carlson opened an e-mail from a veterinary technician and intern coordinator at the aviary. n

“Sorry for the delay in responding to the e-mail you sent regarding the ‘master rehabber’ test. After much discussion among the senior staff, I think at this point we are looking to no longer carry sub-permits. …It sounds like you should have no problem passing the exam and with all the years experience you have it shouldn’t be a problem. We will maintain you on the Federal permit until 2010 so you don’t have to worry about that for a few years. …” n

Carlson saw an immediate problem. Federal and state permits have to be in sync. She couldn’t operate with only a state permit if the aviary held the federal permit separately. It can take six months or more to process a federal permit. She’d also thought that the aviary had obligated itself to the program until the federal permit ran out. n

“When they gave us two weeks’ notice to be done, we were done,” Carlson says. “There was nothing I could do in that short a time to be up and running.” Besides the permits, she says she’d need to get nonprofit designation and do fund-raising on her own. n

“It was a very low blow,” Carlson says. And it wasn’t until she had her lawyer in tow that she first talked to Brown. n

Brown, however, holds the line that the rehab program was simply too risky to continue—even though there had never been a complaint. “Being the permit-holder, we have a responsibility to provide a level of oversight, which we haven’t been doing,” he says. “They invest their souls; they’ve spent time and money to go to remote houses to accommodate injured birds. I’m saddened by where we’ve arrived, but if we are responsible for them, you should have some institutional procedures. We have so much to do here that we have to prioritize our time, and spending time with rehabbers doesn’t meet our top priorities.” n

The aviary has been 70 percent complete for years, and Brown is firm that piecemeal reconstruction won’t happen. Bad for the birds; bad for the visitors. n

Meanwhile, birds are still hitting widows, being shot, landing in sludge ponds and being electrocuted in Salt Lake County. The Ogden Nature Center is taking most of the cases, as the nearest facility with a permit to care for injured birds. n

“Now we have a massive influx of people from the Salt Lake Valley, says DaLyn Erickson, the center’s wildlife specialist. “It’s about doubled our numbers. We’re a small nonprofit rehab facility, and there’s not a lot of funding for that.” n

Volunteers are trying to step in, she says. Still, it is illegal to transport even a little finch without a permit. Owen Hogle, owner of the Wild Bird Center in Holladay, called Brown at the aviary to make a personal appeal for the terminated rehabbers. “I felt this decision was handled very poorly,” Hogle says. “If they had set a timeline so Candy and Tazia could prepare, they could have handled this so much better.” n

The Wild Bird Center gets 10 to 12 calls a week from people with injured birds, Hogle says. That’s just a fraction of the total number of bird injuries, however: Multiplied throughout the valley, that number would be huge. n

Hogle himself has been trying to come up with some alternatives, as have other organizations. n

An emotional meeting that Brown arranged ended disastrously in mid-October. Brown offered to work toward a solution outside the aviary—to write rules and standards, address recruiting new rehabbers and coordinate training—and still plans a Nov. 10 meeting. Carlson feels he just wants to delay resolution until after the bond election, and that he fundamentally misunderstands the program. The two rehabbers had been working under federal standards, recruiting and training for years, although few newcomers stuck with the demanding program. n

And while Brown has now determined that AZA frowns on rehab activities, the original decision—made by a staffer—was simply to terminate without transition. n

Meantime, Brown has been getting calls in “strong opposition” to the bond based on the bird rehab controversy. And he’s incensed at the connectivity of the two otherwise unrelated issues. n

“It’s about the need for us to have more indoor space … so the revenue stream doesn’t drop between September and May,” Brown says of the bond. “It’s a business plan. It’s not about rehab.” n

Carlson—a bird with an injured wing—can agree with that now. tttt