What’s more, he’s gotten under the skin of politicians from both parties. In recent months, the White House took vigorous issue with Beck’s criticisms of senior Obama adviser Valerie Jarrett, and Republican Sen. Lindsey Graham of South Carolina ripped Beck’s cynicism and teary tendencies in an interview with the Atlantic’s Jeffrey Goldberg.

Beck’s would-be interpreters occasionally note that he’s a Mormon: He joined The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) as an adult, in 1999, with his wife and children. But in contrast with former Massachusetts Gov. Mitt Romney, whose Mormonism was discussed in great detail during his failed 2008 presidential bid, the ramifications of Beck’s faith have gone largely unexplored. That’s unfortunate, because a case can be made that Beck is to Mormonism what Father Charles Coughlin was to Catholicism in the 1930s, when the “radio priest” peddled nasty, faith-based opposition to another ambitious Democratic president.

Given the ease with which this discussion could degenerate into Mormon-bashing, this reticence may be understandable. To fully get Beck, though, it’s necessary to understand just how many of his beliefs have specifically Mormon roots or are conveyed in uniquely Mormon ways—from his embrace of former Mormon leader Ezra Taft Benson’s insatiable anti-communism to his Mormon-bred suspicion that the government is the agent of Satan. For some of Beck’s co-religionists, these links are obvious. Back in March, for example, writing on the Mormon-history blog The Juvenile Instructor, Christopher Jones—a doctoral student in history at William & Mary— noted that Beck seemed to be plumbing the disturbing depths of Mormon millenarianism and marveled at the media’s seeming disinterest.

Once the link between Beck’s faith and politics gets made, intriguing questions emerge: Without his unsettling brand of Mormonism, would Glenn Beck still be Glenn Beck? Should members of the LDS Church be cheering or lamenting Beck’s protracted moment in the spotlight? Could Beck’s forays into stealth Mormon sermonizing make his conservative evangelical fans rethink their loyalty? And, if Beck’s religiosity finally becomes a story, what might that mean for the lingering presidential hopes of 2012 Republican contender Mitt Romney?

DEEP TIES TO THE PAST

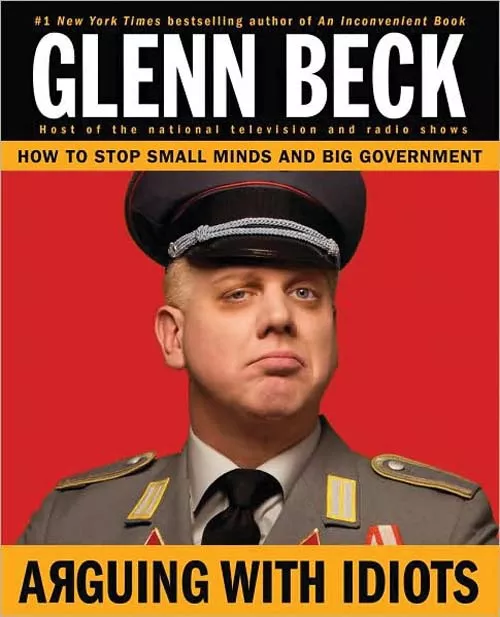

To be fair, the media haven’t totally ignored

the significance of Beck’s Mormonism. In September, Salon published

several stories by Alexander Zaitchik, author of a forthcoming Beck

biography, on Beck’s improbable march to conservative superstardom.

One—“Meet the Man Who Changed Glenn Beck’s Life”—focused on Beck’s deep

ties to Cleon Skousen, an eccentric, prolific Mormon thinker who died

in 2006. These days, Skousen is best known as the author of The Five Thousand Year Leap, a book that dubs the U.S. Constitution a “miracle” and casts the Founders as deeply Christian men. Beck has lavishly praised The Five Thousand Year Leap on

air, and even wrote the foreword for a new edition of the book; as a

result, this formerly obscure text is now a bestseller in its own right.

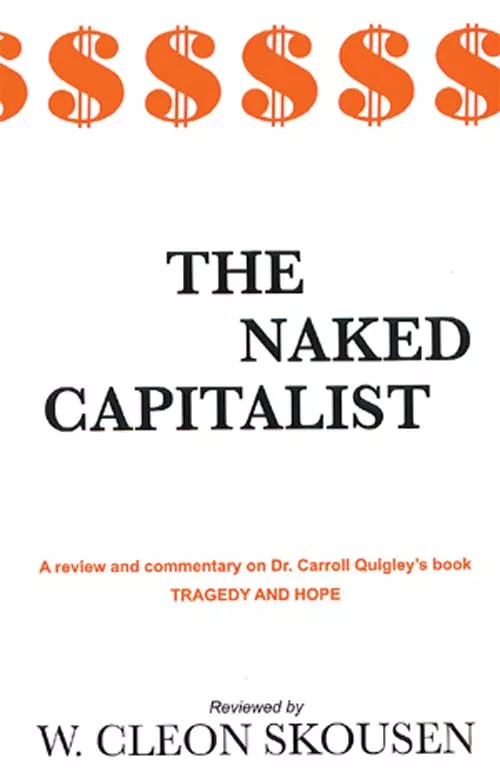

But Skousen wasn’t just a cheerleader for Christianity. He was also a zealous purveyor of conspiracy theories, obsessed with communism in his earlier years, and later warning of a vast mega-conspiracy in which communists and capitalists joined forces to seek total world domination.

Nonetheless, The Naked Capitalist gained

a wide readership at Brigham Young University (BYU), where Skousen was

a professor of religion—and where he apparently taught one Willard Mitt

Romney. (One internecine Mormon squabble, one former president, and one

serious presidential contender … what are the odds?)

Of course, just because Beck’s politics are Skousenian doesn’t necessarily mean they’re deeply Mormon. No intellectual tradition can be reduced to one individual—and in 1979, the LDS Church formally distanced itself from the Freemen Institute, which Skousen founded in 1971 to promulgate his half-baked ideas. (At the time, the LDS Church was led by Spencer Kimball, known for receiving the revelation that finally opened the Mormon priesthood to black men. For his part, Skousen accused critics of this notorious racial ban of using communist tactics.)

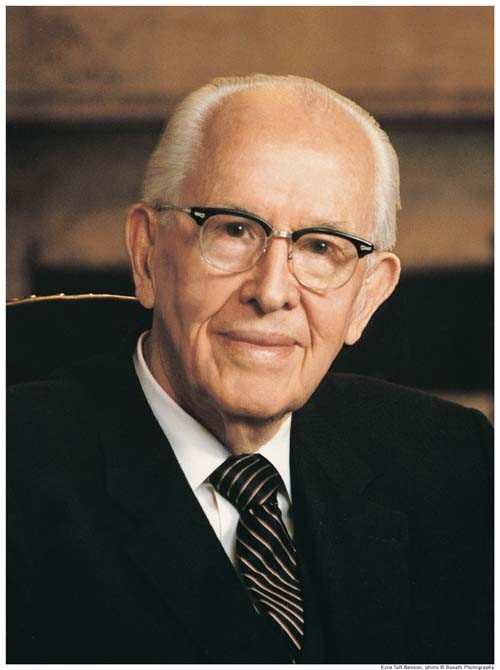

But Skousen is hardly Beck’s only major Mormon influence. His understanding of present-day realities also reflects the paranoid anti-communism of Ezra Taft Benson, who served as secretary of agriculture in the Eisenhower administration and later, from 1985 to 1994, as president and living prophet of the LDS Church.

Beck made his troubling fondness for Benson explicit just before the 2008 presidential election while riffing on the comments of a clueless Obama supporter, who was caught on tape saying that Obama’s election would mean no more gas or mortgage payments. On his Oct. 31, 2008, radio show, Beck cited these absurd remarks as evidence that a dire prediction made by Benson in 1966, during a speech at BYU, could soon come to pass.

Introducing Benson only as Eisenhower’s secretary of agriculture, and omitting any mention of his subsequent role leading the LDS Church, Beck noted that his listeners were likely the same age as Benson’s grandchildren. Then came Benson’s voice, describing an ominous conversation he once had with Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev:

As we talked face to face, [Khrushchev] indicated that my grandchildren would live under communism. After assuring him that I expected to do all in my power to assure that his and all other grandchildren will live under freedom, he arrogantly declared in substance, “You Americans are so gullible! No, you won’t accept communism outright. But we’ll keep feeding you small doses of socialism, until you finally wake up and find that you already have communism. We won’t have to fight you. We’ll so weaken your economy until you fall like overripe fruit into our hands!”

Church and State

Benson

and Skousen were products of the Cold War’s heyday, in which Americans

of all religious stripes were spooked by real and imagined

manifestations of the Red Menace. But they both also emerged from the

distinct culture of Mormonism—which was shaped in its earliest days by

violent conflict with the U.S. government and which still brings its

own unique understanding to bear on key political concepts and

institutions.

Take the U.S. Constitution: As Michelle Goldberg explained in Kingdom Coming (Norton), Christian nationalists of every denomination believe that the Constitution is a fundamentally Christian document—and that the separation of church and state, as currently understood, represents a radical departure from the Founders’ ideals.

But

Mormonism goes a step further. According to Mormon scriptures, the

Constitution isn’t merely a document written by deeply Christian men.

It is, instead, the indirect handiwork of God himself. (See, for

example, Doctrine and Covenants 101:80, in which God explains: “[F]or

this purpose”—i.e., the preservation of moral agency— “have I

established the Constitution of this land, by the hands of wise men

whom I raised up unto this very purpose.”)

Apparently, Beck believes that this terrifying crisis is now at hand (or just thinks LDS apocalypticism makes great radio). On Election Day in 2008, Beck interviewed Utah’s Republican Sen. Orrin Hatch, also a Mormon, on his radio program:

Hatch: You got that right …

Beck: We are so

close to losing our Constitution. We are so close to losing what we

have, and people aren’t thinking. The next generation, our children

will look to us and say, “You sold my freedom for what?”

Hatch: Well, let me tell you something. I believe the Constitution is hanging by a thread.

More recently, Beck used his radio show to propound the Mormon conception of Satan—though many in his audience may not have noticed. On May 5, waxing indignant about governmentsponsored social services—as opposed to freely chosen acts of charity—Beck asked, “Did Jesus say when a man asks for your shirt, you give the government your coat also, and have the government give that coat to the man? No! The government is a middleman. … The government is the devil.”

That’s a bizarre statement—but it jibes with a passage in the "Pearl of Great Price," one of the LDS Church’s canonical scriptures, in which God explains that Satan was cast down after he “rebelled against Me, and sought to destroy the agency of man …” God’s conflict with the devil, in other words, originated with the latter’s attempts to deprive humans of free moral agency. Hence, Beck’s overheated assessment of a hypothetical, government-sponsored clothing giveaway. As Jones, the aforementioned Mormon historian and blogger, immediately noted, Beck’s strange claim was actually a “variation on a standard Sunday School theme.”

Romney’s Apocalypse?

So is Beck’s retro Mormonism responsible for his particular brand of politics?

The prolific historian D. Michael Quinn, who grew up in the LDS Church, makes a similar point. Quinn—who was trained at Yale and has taught there and at BYU—was excommunicated by the LDS Church in 1993 after pursuing several incendiary topics in Mormon history. He suspects that Beck’s conservatism led him to embrace the LDS Church, rather than the other way around. “The combination of Skousen and Benson would have been very attractiveto him,” says Quinn. “I think he’s now sharing with America what originally attracted him to Mormonism.”

Even if Shipps and Quinn are right, though, that doesn’t mean that Beck’s faith is insignificant. After all, thanks to Beck’s chosen LDS influences, he’s currently interpreting the first years of the 21st century via a melodramatic, anxiety-soaked worldview that was established 50 years ago—and which, in turn, was itself grounded in Mormon scripture and the LDS Church’s 19th-century travails. Given this intellectual lineage, is it any wonder that Beck and his fans tend to regard fundamentally political problems— health-care reform, say—as apocalyptic battles between good and evil?

Among some Mormons, meanwhile, there’s fear that Beck’s ascent could reinvigorate a strain of Mormon thought that’s been fading away. Rory Swensen is co-chair of the board of directors of the Sunstone Education Foundation, which publishes the independent, liberal-leaning journal Sunstone; he also writes for the Mormon blog Times and Seasons. In a best-case scenario, Swensen says, Beck’s ascendance could foster discussion of the notion—repeatedly endorsed by the LDS Church hierarchy—that Mormonism doesn’t require allegiance to any political party, even though most Mormons tend to vote Republican.

That said, Swensen worries that Beck could help throw the LDS Church into a sort of ideological time warp. “Mormons tend to be one or two generations behind the broader culture, which is frustrating—a church that espouses prophetic inspiration should be the headlights on issues affecting the oppressed and the downtrodden, not the taillights,” he argues. “On civil rights, we were about 30 years too late. We’re fighting gay marriage right now, but I think you’re going to see the broader culture adopt it—and about 30 years later, we’ll find some way to make it work.”

That’s his hope, anyway. But, Swensen adds, “With Beck tapping into and exploiting mid-20th-century fears of anti-communism and anti-fascism, we might see a resurgence in that culture within Mormonism—and another generation of LDS leaders like Ezra Taft Benson.”

Mitt Romney’s politics are radically different from Swensen’s— but as the Massachusetts former governor girds for another run at the White House, he should probably be concerned, too.

During the 2008 campaign, Romney wooed Christian conservatives by arguing that the doctrinal particulars of his faith weren’t important. What mattered instead, Romney claimed, was that he had faith—that he wasn’t a godless secularist. “While differences in theology exist between the churches in America,” Romney said in his December 2007 speech on faith, “we share a common creed of moral convictions. And where the affairs of our nation are concerned, it’s usually a sound rule to focus on the latter.”

But, as Beck’s example shows, shared moral conviction can mask radically different ideas about important subjects. If the media start examining Beck’s Mormon influences in detail, they just might follow suit with Romney.

That’s

precisely the sort of talk that Romney’s speech on faith was supposed

to quash. Instead, thanks to the converted zealotry of Glenn Beck, the

conversation might just be getting started.

This story originally appeared in the Boston Phoenix.