Ana Canenguez wanted to kill herself when she was 7 years old. But, even on tiptoes, she couldn’t quite reach a tin of rat poison on a shelf at the back of a street-corner shack where she lived in Santa Elena, El Salvador.

She received little affection as a child, her mother having sent her and her younger sister to live with her grandmothers and four other children. When she was 10 years old, she persuaded her mother, who lived in San Salvador, to take her and her sister in. But her situation only worsened, with her mother beating her and her stepfather sexually abusing her.

Desperate to escape, Canenguez moved in with a 24-year-old man when she 14, but he abandoned her when she became pregnant with his son, Jose. She moved back in with her mother to raise Jose, then became pregnant by her stepfather. When her stepfather’s child was born, whom she named Oscar, he was diagnosed with cerebral palsy. She told her mother that her stepfather was Oscar’s father, only to be turned out into the street at the age of 17 with 2-year-old Jose and baby Oscar.

She stood in torrential rain with her son and baby, watching a bus approach, homeless, penniless, wanting to throw herself and her children under its wheels. All that held her back was a profound belief that God would “never leave me alone,” she says in Spanish.

Canenguez’s aunt took them in, and the single mother set about building a new life for her and her children. She rented a small space in a noisy outdoor market and sold handmade sweets. She also met a young man, Job Ramirez, with whom she had two boys, Job and Geovanny, before marrying him in 1993, and then having two more boys, Mario and Erick. They lived in a two-room hovel and Canenguez worked seven days a week selling sweets, then toiletries and biscuits.

She struggled to buy Oscar the medication he needed and take him for checkups to the doctor. “He never spoke, he never told me anything, only cried when he was wet, hungry.” Oscar died at age 13 in 2001. Shortly after, Canenguez and her husband separated.

In early 2003, Canenguez’s brother suggested she come to New York, where he lived. Her plan was to work for two years to earn $50,000, which she calculated would pay off debts to two banks she owed for loans for her street-market business, buy her and her children a house in El Salvador and pay for their schooling. Canenguez, herself educated only through the sixth grade, feels that education is vital, but in El Salvador, little emphasis is placed on attending public school. “If nobody goes to school, nobody cares,” she says.

Just after dawn on Jan. 31, 2003, Canenguez told then-15-year-old Jose that she was leaving him and his brothers in the care of her husband, but that Jose was also responsible for the children, who were still sleeping. “He was very quiet. He almost didn’t say anything.” She hugged and blessed him. “I’m going to come back for you,” she told him. “It’s just for a time.”

Job woke up to find his mother gone. His father told him she would be back in a month. “I was very sad all the years I didn’t see her. Every Mother’s Day, I cried in my room.”

“It’s very hard to leave your children,” Canenguez says. “But you know what’s worse? You get up, your children say they are hungry, and you don’t have anything to give them to eat.”

THE LEGAL ANSWER

Her brother loaned her $6,000 to cross through Guatemala, then Mexico, and then to the U.S. border to reach New York. But her expectations of making money “so I could fill my children’s emptiness” were quickly dashed. She worked for her sister-in-law cleaning houses but earned only $100 in the first week. That, she says, was what she earned in a week selling 50 boxes of biscuits in the San Salvador market.

After several months in New York, she moved to Utah in May 2003, at the urging of an acquaintance in Ogden. She worked in a Mexican restaurant, seven days a week, from 9 a.m. to closing, and was paid less than minimum wage. She sent nearly all the money she earned to her children’s father for their food and to pay bills.

In August 2003, Canenguez moved in with Mexican national Eusebio Granda. After a year without work because of a blood disorder and the birth of Luisito, her son with Granda, in late 2005, Canenguez asked her oldest boy, Jose, then 18, to come and join her. She wanted him to work so she could send more money to his brothers in El Salvador. Her husband looking after their four children in El Salvador “asked for more money than I had. He thought you come here, and there’s money in the street.”

Granda found work on local farms near Tremonton, a small town in northern Utah. Their two American-born children, Luisito and Katy, attended preschool for two years in Honeyville at the Centro de la Familia, a federally funded Utah agency that helps the families of migrant workers.

But when the lives of her four children who remained in El Salvador were threatened, she knew she had to do more than send money and hope for a better future. She paid for two children to be smuggled over the Mexican-U.S. border in May 2010, then went herself in 2011 to Mexico to rescue her last two remaining children when her attempt to smuggle them from El Salvador to the United States resulted in them being picked up by Mexican federal officers.

But when she tried to cross the border into the United States with the two children to bring them back, illegally, to Utah, they were arrested. Now, she and four of her sons wait while their two deportation cases are appealed to the Board of Immigration Appeals and the 10th circuit court.

This is the heart of the immigration debate, argues Randy Neal, an immigration attorney who, for 18 months, was an attorney within Immigration & Customs Enforcement (ICE) prosecuting cases before Salt Lake City’s immigration judges. “A vast majority of immigrants cannot understand that you have to have permission to make this country your home. Somebody who is born in El Salvador, who wants a better life for their family, doesn’t understand why wanting that isn’t enough. The real question is, do people have a right to relocate for a better life? The legal answer is no.”

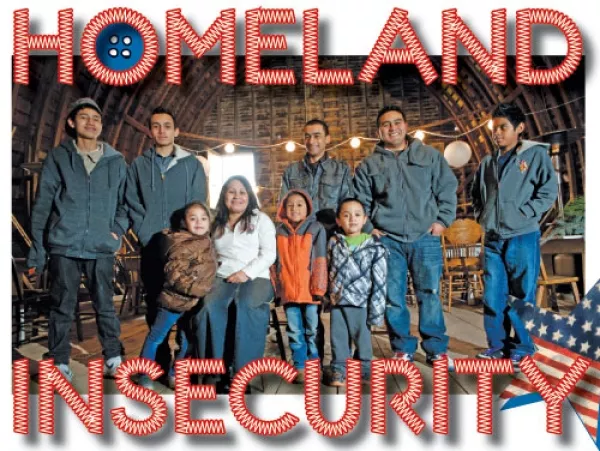

In the few years that Canenguez has had all seven of her living children under one roof, she and they have been committed to education, to the point where her second-oldest son, Job, has won accolades at school and she was named Utah Head Start’s Parent of the Year, just days after she was ordered deported. When it comes to the Canenguez household, it seems the federal government seeks both to help her youngest children, through their preschool and migrant-worker program, and at the same time tear away the person who is so important to their nurturing and future education.

By mid-December, all Canenguez could do was hold out for a miracle, as her attorneys prepared appeals and a request for prosecutorial discretion sat on the desk of an official in Salt Lake City’s ICE office. If prosecutorial discretion were granted, it essentially meant that ICE agreed that she and her children are not significant enough a concern to warrant their limited resources, and they would shelve their cases.

Her attorney, Sharon Preston, argues it’s hard to think of someone who deserves prosecutorial discretion more than Canenguez. “When you’re praising people who want to be members of this society, who really wanted it, it’s her.”