When Nelson Gonzalez handed over his passport to an immigration officer at the Atlanta international airport, the man asked him why, if he were coming for a week-long tryout with Real Salt Lake, did he have a three-month tourist visa?

The nervous 20-year-old Argentine, who spoke no English, was delayed by officials but eventually allowed to enter the United States, only to find he had missed his connection to Salt Lake City. The check-in attendant laughed at Gonzalez when he showed his ticket. For several hours that July 31, 2009, evening, Gonzalez walked around the Atlanta airport in tears. Each time he returned to the check-in, the attendant laughed in his face.

“I felt impotent,” Gonzalez says in Spanish. “I had no phone, no computer. I started to cry. I needed my mother.” A man loaned Gonzalez his phone to call his Miami-based agent, who in turn spoke to the phone’s owner and asked him to get a Spanish-speaker to help Gonzalez change his ticket.

Gonzalez arrived in Salt Lake City that same night, where he stayed in a hotel room, alone, without money and only three pieces of clothing for four nights. His misery ended only when fellow Argentine and Real Salt Lake midfielder Javier Morales moved the desperately homesick Gonzalez into his Sandy-based townhouse for two weeks. “He loaned his family to me,” Gonzalez says. “The debt I owe him is impossible to repay.” Morales’ gesture eased Gonzalez’s ache for his family’s home in a poor Buenos Aires neighborhood.

- BY ERIK DAENITZ

- NELSON GONZALEZ

Gonzalez and Morales were part of a lengthy wave of mostly Latino players imported by coach Jason Kreis to help fill a roster of 28 players that he had gutted by two-thirds. “[North] American players fight to win,” Real general manager Garth Lagerwey says. Argentine and Colombian players share a similar understanding of “esprit de corps, of a warrior mentality, a willingness to fight together. MLS can be a brutal league, and those guys are technically good enough to rise above that brutishness.”

Real players such as Argentines Gonzalez, Morales and Fabian Espindola and Colombia-born and ex-Deportivo Cali player Jamison Olave each journeyed from economically troubled backgrounds to eventual athletic prominence and financial reward in the United States. Olave grew up in La Iguana, a shantytown outside Medellin beset by killings from drug “combos,” or gangs. Olave got out, along with his family, despite the regular appearance in the streets of bodies at dawn and the death of a friend who ended up a drug addict. After three years playing for Real, Olave recently became a naturalized American citizen, bringing his son from Colombia to Utah to enjoy what striker Espindola calls “a paradise.”

Soccer opens up a fault line in the invective-stained landscape of immigration in Utah. On one hand, Real Salt Lake is replete with stories of legally imported Latinos from hard-scrabble backgrounds fulfilling the American dream. On the other hand, the Salt Lake Valley also teems with the struggles of thousands of predominantly Hispanic children and adults who, coaches say, yearn to play for Real but, because of their or their parents’ immigration statuses, are barred from their dreams. Whether as an escape from poverty in South America or simply from Utah’s anti-immigrant headlines and political initiatives, soccer for many in the Hispanic community is ultimately a refuge. No more so than at Real’s Rio Tinto Stadium, where the sport offers, says Sen. Luz Robles, positive images of successful Latino immigrants for Latino children and a “safe environment” for Utahns to cheer on Hispanics, “where nobody cares about a broken, 40-year-old immigration policy.”

WINNING LATINO HEARTS

Real’s Latino players have not only found a second home in Utah, many have become fan favorites. After Chivas USA’s Marcos Mondaini tackled Javier Morales during a game in Sandy and snapped his ankle, sidelining Real’s most talented player for five months, fans responded with large signs the following game proclaiming, “Get well soon, Javi, we love you.”

But for local Latinos, Anglo adulation of imported Latino players offers irony and also frustration. “Pepe” [a pseudonym] coaches young Hispanic children of mostly undocumented parents for free at a West Valley City soccer academy founded by his father, “Pelon.” Both are undocumented. Pepe says a strong perception among Latinos is that imported Latino players, “born with the ball stuck on their foot,” he says, are necessary for American teams whose Anglo players can be “robotic. They need a few Latinos to provide breakaway speed and use them to make their team.”

Whether those Latinos will one day include talented local youngsters such as 10-year-old Henry P. is an issue as much weighed down by the convolutions of local and federal immigration polices as the difficulties of professional sports. In Utah alone, thousands of talented high school athletes will never see the pros. For undocumented children, or the children of parents without papers, the chances are far dimmer.

Henry plays defender for Pepe’s club and won its best-player trophy in 2010. His father, Miguel, struggles to find work week-to-week to feed his family. “Being illegal means having to find your own destiny,” Miguel says. “My dream is that Henry plays professionally for Real Salt Lake.” But Miguel’s undocumented status means that the road to his son’s promising future is littered with obstacles, not the least of which is finding the money to pay for inscription into the weekend league. [Though Henry and other youths who play in the West Valley City soccer are citizens, their last names have been withheld to protect their parents, many of whom are undocumented.]

- BY ERIK DAENITZ

- HENRY P.

With no federal immigration solution in sight, West Valley City soccer academy founder Pelon believes the only answer for undocumented parents and the children he teaches is to put aside their fears and concerns over their future and focus on developing their children’s sports and education. Pepe’s club runs on the goodwill of its players’ parents and the passion of its volunteer coaches. Pelon says his club desperately needs financial support from someone “who cares about the futures of our children.” But when Miguel asked a former employer to purchase uniforms for some of the children, he says the man replied, “I don’t give money to children of drug addicts.”

Naturalized American and local soccer coach Gerardo Bellazatin has lived in Utah for 30 years. It grates on him, as it does several other Latino coaches City Weekly spoke with, that some of the very Anglo fans who cheer on Morales and Olave are, Bellazatin says, the same individuals “who vote to pass all these measures making it easier for [Hispanics] to be deported.” Indeed, Real’s stands, it appears, are not immune to the racism that arguably permeates recent political initiatives to force immigrants out. When Mexican team Monterrey scored against Real in April, Bellazatin jumped up and cheered. More than a dozen neighboring spectators, he says, shouted at him, “You fucking Mexican. Go back to your country.”

Like other coaches, Pelon says he’s hopeful that Real’s presence in Utah offers both opportunities and influence for some of the children he trains. “I don’t lose hope that all the kids in our club will somehow one day be part of Real,” he says.

- BY ERIK DAENITZ

- HECTOR, 16, TRAINS WITH PELON AND PEPE'S WEST VALLEY SOCCER CLUB

A third-generation Dutch immigrant, Real’s general manager, Garth Lagerwey says, “There’s a lot of darn good players in the Southwest and many of them are slipping through the net. It’s our job to show Hispanic players there’s a future in Real.” Part of that job was to open the Real Salt Lake academy down in Casa Grande, Ariz., close to the Mexican border. Real “planted the flag there,” Lagerwey says, to show disenchanted Mexican-Americans “that they could have a future playing soccer in the U.S.” Twenty-four children, ages 14 to 18, from Utah and Arizona “live, eat and breathe soccer,” he enthuses. Real and an investor put into the athletic development in total $500,000 each year.

While amateur coaches hint at below-the-radar scenarios used by professional clubs to get papers for talented undocumented players, others, such as Bellazatin, who owns Futsal Academy, and undocumented coaches Pelon and Pepe pursue sorely underfunded academies to train Latino children in soccer. If one day, a Utah Latino in a Real shirt steps onto Rio Tinto’s pitch, that may well have a significant impact on both Real’s financial and Utah’s political outlook. Bellazatin arguably speaks for many of the Hispanics Real seeks to woo in Utah when he says, “Until you bring onboard homegrown talent, then my heart will not be theirs.”

Lagerwey acknowledges he is “likely to stumble upon undocumented kids who would make us a better team. We as Americans need to have a debate. These kids came here through no fault of their own, and they have natural talent. Should such kids be denied a path to American citizenship?”

THE GOOD LIFE

When Real coach Kreis in late 2007 looked into Fabian Espindola’s eyes, he saw what he was looking for. Kreis sought more than just talent; he wanted drive. “When Fabian talked, he had a real hunger in his eyes. It was almost spooky. There was a killer mentality about him.” Espindola knew that Real was playing a friendly match with Boca Juniors, his former team. “I want to kill them,” Espindola told him.

“That was what I wanted to hear,” Kreis says.

Espindola attributes that appetite to his nationality. “You are born watching futbol,” the 26-year-old says. “You fall in love with the game.”

He comes from Merlo, a small rural town dotted with humble houses with terracotta roofs and dusty streets, 12 hours by bus from Argentina’s capital, Buenos Aires. Spotted by a scout for the legendary Buenos Aires team Boca Juniors, then-10-year-old Espindola worked after school roofing and cutting grass to pay for a pair of cleats and a bus ticket to Buenos Aires for his tryout.

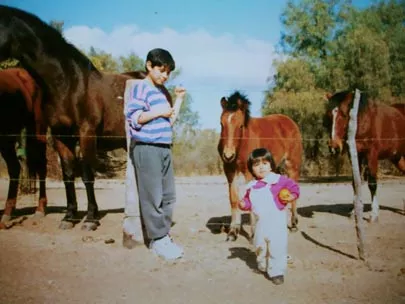

- COURTESY FABIAN ESPINDOLA

- FABIAN ESPINDOLA & HIS SISTER GROWING UP IN MERLO, ARGENTINA

His father raffled off a piglet as a prize to help pay for the trip. When Espindola arrived at Boca, he saw 300 other children waiting to try out. “I thought I didn’t stand a chance.”

For the next eight years, Espindola lived in a pension [boarding house] near Boca’s stadium, La Bombonera, with other children from across Argentina. He was given food and a bed, went to school and, for the rest of his adolescence, other than 15 days off in the summer and 15 days off in the winter, belonged to Boca. “It was very, very demanding. If you don’t give everything you have, next year, someone else who wants it more will take your place,” he recalls.

Javier Morales comes from a middle-class background. His parents owned and ran a small street-corner market in Temperley, on the outskirts of Buenos Aires. As a child, Morales would sell cold cuts, cheese and biscuits from square tins that lined the shelves. “It was a good business, the good life,” Morales says. But rampant inflation in the early 1990s forced Morales’ parents into bankruptcy. His father became a taxi driver, his mother a janitor for a local school.

Club Atletico Lanus signed Morales to an exclusive “formation” contract from when he was 13 to 18. When Morales was 20, the day he received a letter offering him a professional contract with Lanus, another letter arrived for his parents announcing their home’s auction for unpaid debts. Much of Morales’ Lanus salary went to paying off the debts, saving his parents’ home. “It was one of the biggest satisfactions of my life,” he says.

Espindola and Morales both found heartbreak with their soccer careers in Argentina. Despite his all-consuming love for Boca Juniors, Espindola left the club after five games with the first team because he knew with so much established talent on Boca’s bench, his chances to shine were, at best, limited.

Morales, after four successful years at club Arsenal de Sarandi, was abruptly let go in favor of another player of similar skill. “Futbol es ingrato,” Morales says. Soccer is ungrateful. “It isn’t like life, where your parents are always there to come home to.” One coach told him, “Soccer is today. Yesterday never happened.”

HITTING A WALL

Espindola and Morales came to Utah courtesy of visas sponsored by Real. “Chuky” was 10 years old when he crossed the Mexican border illegally. The now-24-year-old West Valley City resident recalls hiding behind a boulder with his mother and sisters as the arcing beams of border patrol officers’ flashlights stabbed into the darkness nearby.

Chuky was a gifted soccer player, according to several friends and family, always practicing with a ball in the streets of Midvale. His teacher wanted him to apply for soccer scholarships, but Chuky didn’t see the point. “I didn’t have papers and I didn’t have money. Ya pasé mi historia.” That’s my story.

He and his wife rent a small, neat home in West Valley City, their living room shelves lined with ceramic angels, adult soccer cleats piled up by the sofa. Chuky’s dream of playing professionally has long since faded, he says sadly. Though he’ll never be paid to play the game he loves, he and friends play in late night six-a-side soccer teams that gather post-work in rented halls in Salt Lake City’s back streets or in one of the Sunday all-day Mexican ligas on soccer fields across the valley.

Adolfo Ovalle has known many Chukys in Utah. He sits in the Layton office of Utah youth soccer club La Roca [The Rock], over his shoulder a photograph of the Chilean championship team Universidad Catolica, where he played defender. After a 10-year career as a professional soccer player in South America, Ovalle signed with Utah Blitzz in 2000, a third-division team with players from Argentina, Northern Ireland and Colombia. Five years later in 2005, Ovalle set up nonprofit La Roca, to “develop kids to send to college [to play soccer] at 18.”

A common complaint from Hispanics about clubs like La Roca is that they cost $1,000 to $1,500 a year to join. That’s not true, Ovalle says. In La Roca’s case, there’s a $160 club fee and then a nine-month to one-year cost of $360 to $720, depending on age. In 2010, Ovalle says, his club spent $30,000 on scholarships for players, mostly Latinos who couldn’t participate without the club’s help. While critics argue that money goes only to talented prospects, Ovalle says it’s a lack of resources, not talent, that determines who gets help.

When Latino children play at La Roca, Ovalle sees “happy kids kicking a ball. They don’t have a clue [what faces them]. But when they get to 16 or 17, what I see is it’s almost like they hit this wall, they understand their reality. Some of them lose a tremendous amount of interest. Some of them realize to get scholarships they have to be American. It’s a huge slap in their face. It makes me sad.”

At regional trials and matches, Ovalle asks coaches what can be done for talented, undocumented players, only to be told nothing. But while NCAA scholarship programs aren’t available to undocumented youths, he suspects some junior colleges are more accessible. Other possible routes for undocumented youths to pursue include adoption into American families or returning to their birth countries and coming back to the United States with a contract offer from an interested team.

CHAMPAGNE GLORY

In November 2009, Kreis’ team-building efforts brought forth bold fruit. His team reached the Major League Soccer cup final. Fifteen minutes into the game, L.A. Galaxy’s star David Beckham tackled Morales hard. Morales tried to continue, but his knee was injured too badly. “I asked God to take the pain away, but I couldn’t walk.” Real stalwart Andy Williams told him it was OK. “They were going to win for me.”

Morales’ departure galvanized his blue-collar, underdog team to a hard-won victory over the multimillion-dollar Galaxy roster. “There was madness in the locker room,” Olave recalls. “We were shouting, singing in Spanish and in English, [drinking] Champagne.” His voice chokes, the memory still emotional two years on.

Real’s reward for their victory, along with national recognition and grudging respect from Utah Hispanics for defeating the Galaxy, was to meet President Obama.

In the White House, Kreis looked around at his Hispanic players and wondered, “Do they know the big deal this is?”

Some did more than others. Olave recalled going with former Argentine teammate Matias Cordoba to photograph the White House the previous summer while Real was in Washington for a game. Morales ridiculed them for photographing the wrong building. A year later, Olave marveled, he was shaking Obama’s hand.

In Merlo, San Luis, Argentina, the local paper and radio broadcast Espindola’s encounter with Obama. “I never thought to imagine the things that football gives you,” Espindola says.

A LIGHT OF HOPE

In a small West Valley City park on a late Thursday afternoon, an intense 43-year-old carpet installer looks on proudly as 5-year-old girls and boys take turns chipping a ball around a lineup of small boys. “Champions are made on this field,” club founder Pelon says. He gathers around him 30 children and urges them to train hard. “Somos una familia deportiva,” he tells them. We are a sports family. “Futbol is for this. To unite.”

The club is a 2-year-old initiative run by undocumented father Pelon and 23-year-old son Pepe to provide free soccer training for Latino children. “Futbol is a light of hope for our children,” Pelon says. That hope extends to Pepe, who through training children with his father found not only his own journey to redemption but also a career path to, he hopes, professional coaching.

- BY ERIK DAENITZ

- YOUNG PLAYERS AT THE SOCCER CLUB

At the end of the training, Pepe addresses the two teams he has been working with. “What we do here may not look like much, but it has results,” he says. “These little Mexican teams have beaten American [youth] teams.”

Pepe came to the United States when he was 1, on a tourist visa. He was banned from high school trips because he could not provide a driver’s license or a Social Security number. “Teachers told me I could grow up to be a doctor,” but he knew that was not true. “I was trapped with nowhere to go in a place that didn’t want me.”

While Espindola and Morales spent their teenage years locked into training, Pepe also skipped his adolescence, but in favor of joining a gang. “I was picking fights, robbing people. I knew the consequences. I didn’t care. I lacked empathy.” Unemployed in Orange County, Calif., he called his father, who had settled in Utah in search of work and direction. “I want to change,” he told him. “I want to be a better person.”

Pepe took a Greyhound bus to Salt Lake City on May 29, 2010, and the day he arrived, he laid carpet with his father, then went with him to the club. “Give him the respect you give me,” his father told the children.

What frustrates Pepe, as it does other coaches of financially challenged clubs, is that larger academies lure away the cream of talented players from under-resourced clubs. One club scout, Pepe says, approached the parents of three of his players with offers of paid travel expenses and scholarships. Because the parents are committed to Pelon and Pepe’s vision of a grass-roots soccer academy, they elected to stay with the club. Larger clubs, amateur or professional, Pepe says, can be “like vultures going after the best talent. We don’t have money, and they use it to their advantage.”

This is a bittersweet dilemma for coaches like Pelon and Pepe and La Roca’s Ovalle. “You’re losing the best player on your team, but he has that opportunity, which is probably what every player wants most,” Ovalle says.

FOR THE LOVE

OF FUTBOL

For some professional Latino imports, just making it to the United States is not enough. Nelson Gonzalez is uncertain whether he will stay. He “feels bad” sitting on the bench game after game. In mid-June, a week before he had decided, without consulting Real, to fly back to Argentina, coach Kreis, learning of his plans, called him and advised him, Gonzalez says, “Don’t go crazy.”

Gonzalez doesn’t want to “go home with my arms empty,” he says, having come to the United States and not played. That’s a dilemma Real’s Lagerwey says that North American players face when deciding whether to go abroad to play in foreign leagues to pursue their careers. “You have to decide whether you want more playing time or more money,” Lagerwey says. With Gonzalez’s loan contract to Real up in December, whether Real and the young Argentine will continue their association remains unclear. “Quiero jugar. Otra cosa no hay,” Gonzalez says. I want to play. There’s nothing else.

Espindola agrees. After he failed to capitalize on a chance to score against Mexican team Monterrey that would have taken his team to the world finals, he shut down. For three days he locked himself inside his apartment with his wife, Barbara, not speaking to her that first day, watching the game over and over, asking himself, “Why didn’t I do it?”

Barbara is used to his dark moods. “I don’t ask questions.” Soccer, she says, is “everything. It’s what gives us food.”

- BY ERIK DAENITZ

- FABIAN ESPINDOLA

%uFFFD

Since then, though, Espindola has notched six goals this season for his team. “That’s what they have me for,” he says.

Kreis has a special place in his heart for Javier Morales. “El idolo,” Espindola says, not unkindly. In Morales’ demeanor, Kreis finds defined the sense of “quiet self-belief” he says has taken his team so far.

Whether intended or not, out under the floodlights of Rio Tinto stadium, Real Salt Lake’s Latino stars and the regard they are held in by their fans implicitly asks for tolerance and inclusion on an issue where many see only rejection. In the face of such intolerance, 10-year-old Henry P.’s calm gaze seems unwavering. “Talent-wise, the sky’s the limit for Henry,” his coach Pepe says. But American citizen Henry faces complicated decisions, since his undocumented parents will be unable to support him as he tries to take a path that is already fraught with difficulties. “It usually comes down to heart and how much you want it,” Pepe says.

If children like Henry are to one day find a future in Utah, whether in soccer or in a professional career as a doctor or an educator, perhaps it might be found in the sentiment Kreis offers to his players, when the coach notes that every player on his team, “has been discarded somewhere. They were somebody’s outcasts, now you’re ours and we love you.”

Click here to read about Real Salt Lake midfielder

Jean Alexandre's journey from Haiti to Utah.

- BY ERIK DAENITZ

- JEAN ALEXANDRE