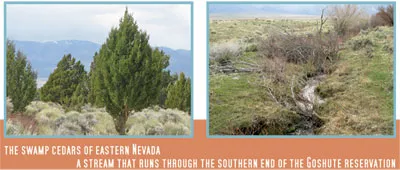

In Spring Valley in eastern Nevada, the swamp cedar trees stand in somber silence. No more than a mile or so long, they are a narrow strip of sentries marking the place where, the Goshutes say, men, women and children belonging to the Goshute and Shoshone tribes were massacred in 1863 and again in 1897. In this hushed grove, the Goshute, along with the Duckwater and Ely Shoshone tribes, come to mourn and conduct spiritual ceremonies.

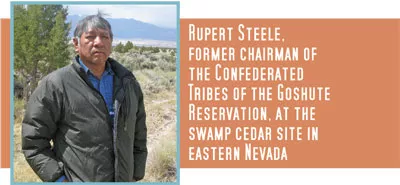

Rupert Steele picks off a piece of cedar bark and rubs it up and down an eagle feather. The former chairman of the council of the Confederated Tribes of the Goshute Reservation then throws tobacco in different directions at the entrance to the swamp cedar grove and sings a sacred song in Goshute. He explains he’s acknowledging the spirits of those killed by the U.S. military and giving them thanks “for letting us come here and visit with you at your house.”

Steele and the elders of his tiny tribe—out of 539 enrolled tribal members, approximately 200 live on the Goshute reservation in Deep Creek Valley, Utah—believe that where each murdered soul fell, the nutrients of their remains fed both physically and spiritually the swamp-cedar trees. “Otherwise you’d never see swamp cedar grow this tall and strong,” he says.

As Steele sings, he “feathers up,” fluttering the eagle feather up and down his body so that the spirits he has brought with him stay outside the swamp cedar site. Then he blows through an eagle wing bone, summoning the spirits of his ancestors. “I want spiritual help, I want them to be with us.”

That help is needed because the Southern Nevada Water Authority (SNWA) wants to run a multi-billion-dollar, 300-mile pipeline up to Spring Valley and four other valleys on the Nevada-Utah border—one of which, Snake Valley, is in Utah—to pump billions of gallons of groundwater to parched Las Vegas.

SNWA’s spokesman, J.C. Davis, says the project is about finding an additional water supply for an area that is 90 percent dependent on the Colorado River, a rapidly diminishing source. The project includes not only the buried pipeline, but also overhead power lines, numerous electric substations, pumping stations and a storage reservoir. SNWA’s position is clear, Davis says: “All we can do, all we have done, is ask permission to use resources that the state dictated was available.”

If the SNWA does eventually begin pumping, Steele and the tribe worry it will kill the swamp cedar and drain aquifers that extend into Utah and lie under their 113,000-acre reservation—a two-hour drive from the swamp cedar—turning their harshly beautiful land into a dust bowl. That’s a fear Davis calls “patently false,” arguing that the Nevada State Engineer, which oversees water rights, focuses on “making sure whatever pumping occurs is sustainable.”

The homes and ranches in Ibapah rely solely on reservation springs and streams to survive. Much-needed income is also derived from hunters attracted to the reservation by prolific herds of elk. But beyond all that, the Goshute say their very religion and their right to pursue their beliefs and culture both on and off the reservation are at stake.

“Every plant, trees, grasses, weeps with our blood which was spilled on this land,” Steele writes in an e-mail. The tribe’s “spiritual strivings, our mysticism, our relationship to nature, and our quickening desire for justice and peace” stem from a love of the soil of “our fathers and mothers, the metaphysical meeting of their personalities, temperaments, and bodies with this land.”

Water is fundamental to the Goshutes’ beliefs, and they fear losing to Las Vegas’ thirst the sacred waters, around which their ceremonies revolve, that tumble down 11 streams from the Deep Creek mountain range. In the Goshute language, Steele says, water is referred to as a human being, a living entity. It is in the water that the spirits of their ancestors reside. If the water goes to Las Vegas’ fountains and man-made Venetian canals, the spirits will go there, too.

SNWA’s Davis characterizes fears that his agency’s plans could wipe out the tribe as “hyperbole that doesn’t advance their cause.” Nevertheless, he acknowledges that the lack of pumping in rural Nevada means “we don’t have a lot of historical pumping to base projections on” as to how aquifers will respond.

In 2011 hearings before the Nevada State Engineer, an SNWA attorney questioned whether the Goshute beliefs are akin to a child’s belief in the bogeyman. Goshute attorney Paul Echohawk found such comments “shocking and offensive” and one tribal member “left the room in tears.” The attorney later wrote a letter of apology to the tribe, but it did not placate Ed Naranjo, tribal council member and tribal administrator. “It’s like we believe in fairy tales,” he says. “That we’re nothing.”

EVERYTHING’S CONNECTED

Deep Creek is a land swept by winds from both the north and the south. “This is where they meet and fight,” Steele’s father would tell him. This community is so small that everyone knows everybody else’s business. While the council and tribal members have fallen prey in the past to personal agendas and factionalism, before Las Vegas’ threat they have found a new unity.

In March 2012, the Nevada State Engineer ruled that despite the protests of the Goshute tribe—along with those of other tribes, ranchers, the LDS Church and other local landowners—Spring Valley could be pumped in monitored stages by the SNWA. Only litigation, including an April 2012 appeal of the engineer’s decision by the Goshute and two Nevada tribes, and a shortly expected environmental-impact report by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) stand in the way of a giant Las Vegas straw suctioning water from aquifers in rural Nevada near the Utah border. And no one knows for sure what the impact will be.

According to hydrologist Tom Myers, who testified at the Nevada state engineer pipeline hearing in 2011, while pumping Spring Valley groundwater may not impact the reservation for 200 years, pumping Utah’s Snake Valley could have a much quicker impact, even if only a few feet. But in Ibapah, which has suffered increasing drought in the past decade, even a few feet could be devastating, say tribal members and nearby ranchers.

The aquifers beneath Spring Valley, neighboring Tippett Valley and the reservation are all connected, Steele says, in the same way that his thumb is connected to his big toe. SNWA’s Davis rather compares the valleys’ aquifers to “a series of adjacent bathtubs, many of them sharing walls, some with cracks in them. Water does move from one basin to another, but it doesn’t move freely, by any stretch of the imagination.”

While deputy Utah State Engineer Boyd Clayton says that all the scientific information his office has seen suggests that SNWA’s pumping will not affect Deep Creek, he says that “there’s never been pumping of this magnitude before. If you withdraw that much water, there will be change, there’s no avoiding that.”

Dan McCool teaches political science at the University of Utah and is an expert on water resources as well as American Indian voting and water rights. He describes the pipeline as part of the “hell-with-you” water policy that has long defined the American West’s attitude to owning natural resources rather than sharing them. “There is absolutely no legal, ethical or moral cognition of what impact this has on other people,” he says.

Though a passel of organizations and communities—including Salt Lake County—originally protested the plan, no one in government, it seems, is currently stepping up to protect the Goshutes. The Goshute are a sovereign nation, with their own tribal government, but Steele says when it comes to negotiations, whether with federal or local government, “they always put the Indians on the back burner.” Steele says part of the U.S. government’s treaty with the tribe involved the feds providing “welfare and safety for perpetuity.” Yet the federal entities charged with doing this, most notably the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) and the BLM signed a stipulated agreement in 2006 with SNWA withdrawing protests to the project, without consulting the tribe. According to the Las Vegas Sun, a BIA director said that the timing of negotiations between the federal agencies and the SNWA did not allow for consultation with the tribe, a claim tribal leaders dispute. The BIA did not respond to e-mailed questions for this story.

“We relied too heavily on the BIA,” Naranjo says. “We have to do things for ourselves.”

Utah Gov. Gary Herbert has yet to decide whether to sign an already-drafted 2009 agreement with Nevada over Snake Valley, or fight Utah’s neighbor in court. If Herbert signs the agreement, Steele says “it will be a big slap in the face.” Three times, he says, Herbert promised to help the tribe with water-related issues, and each time nothing materialized. “That’s a ‘no’ in my book.”

Ally Isom, Herbert’s deputy chief of staff, says Herbert has made no decision regarding the agreement, but has been “consistently supportive of the Goshutes and hopes for their success as a people and as citizens of Utah.”

Steele argues that having put their trust in government, now tribal members trust no one, including their own leaders. “Some people have given up,” he says. “The spirituality gets away from them. Some refuse to leave their homes, they’re afraid of the outside.”

“WHEN IS ENOUGH?”

Professor McCool spies a deeply unsettling factor in the “horrendously unjust” future the Goshutes face at the hands of Nevada’s water policy. In the American West today, he says, “there’s still a huge amount of animosity, of racism against the Indians.”

The Goshute lands once stretched from the Great Salt Lake to Nevada. In an 1863 treaty, the U.S. government assigned the Goshute to a fraction of that space. Ultimately, two reservations were created for the two Goshute tribes: Steele’s tribe, the Confederated Tribes of the Goshute Reservation [CTGR], which live on the Nevada-Utah border; and the Skull Valley Band of Goshute Indians of Utah, which live near Dugway Proving Grounds.

Federal agencies attempted to force the Goshute into farming and agriculture, a lifestyle many in the tribe rejected, leading to poverty, high unemployment and strife with local and national authorities. “They put us out there, thought we’d die anyway,” Steele says. “And guess what? We never died off.”

Genevieve Fields is the tribe’s enrollment officer. She can’t imagine living anywhere else. “Here I go up to the creek, I cut willows to make baskets. I pick berries, dig wild onions, wild potatoes. I find dye and add colors to my baskets. I can live without that,” she says, pointing to a light bulb, “but I gotta have water.”

If the water is taken from their land, “What’s going to happen to our little kids who live here, to the old people? We’ll have no place to go.” She compares the reservation’s residents to those who fell in the swamp cedar massacres—the haunting history of which, unlike the Mountain Meadows massacre in southern Utah, has gone mostly undocumented. As back then, she says, “they want to just completely see us gone.”

Council member Madeline Greymountain detects a historical pattern. “Every time native people come to harmony, peace with the land, somebody comes along who wants more and more. Nobody’s satisfied.” That’s a fate many tribes have suffered, she says. “What more do they want? When is enough?”

BACK POCKET SONGS

Ibapah lies an hour south of Wendover, through a west desert landscape that in the early morning sees craggy mountain faces and valleys of yellow grass covered in a milky mist.

A rickety sign announces Ibapah, which means cloudy, churned water. After a few outlying farms, you pass the elementary school, a ward house of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and then the tribal offices, the valley’s only employer.

Nearly all the tribe’s members were raised LDS, but many now belong to the Native American Church. Steele says the U.S. government enlisted the Mormon church in its fight to eradicate native religious beliefs and cultural ways. Steele recalls being baptized into the Mormon church as a child. It was either that, he says, or his family would lose access to state benefits.

His father taught him about “the sacredness of the land and his mother “the circle of life and how to use our water in ceremonies.” When Steele was 12, he was sent to an Indian boarding school in Nevada, where he could not speak Goshute. “They wanted to get us away from Indian thinking, Indian living.” So he put his father’s songs about the water, the sun and the moon, “in my back pocket.” His plan was to get an education, to learn the ways of the outside world, then go back and help a reservation racked with unemployment, alcoholism and drug abuse. He’s lost six of his eight siblings to alcohol-related deaths.

Greymountain was also born on the reservation, her father a full-blooded Navajo, her mother half Goshute, half Western Shoshone. As a child, she drank out of the stream by her cabin. “The water was very, very cold—kind of crisp, sweet.”

Greymountain was only 14 when her mother died in an alcohol-related car accident. Later, Greymountain successfully overcame alcoholism, unlike her father, who drank himself to death. “When you fight for your life back, you truly don’t take it for granted.” That personal battle she contrasts with her tribe’s fight over water now. “This one is all of us, it ties all of us together, it’s bigger than our personal struggles.”

Along with the struggle to deal with entrenched social and addiction issues, the tribe has faced a long, unsuccessful battle to bring jobs to the isolated valley. There’s so little money on the reservation, “whatever you have, you spend,” Steele says. “A lot of them live on fixed income. It’s real important to get economic development to put these guys to work.” While the tribe has the labor, it lacks managerial or administrative skills, he continues. The tribe opened a welding business in 1969 but it only lasted a few years, strangled by Ibapah’s isolation and the imposed transport costs of shipping steel work out. “We got really left behind,” Steele says.

DESERT REALITIES

Steele’s one regret as tribal council chairman, he says, is that he put all his eggs in one watery basket. In 2007, the tribe applied to Utah to appropriate 50,000 acre-feet of water to build a reservoir on the tribe’s land that could then be used to generate power. Their water application to the Utah State Engineer made local ranchers nervous.

It “was a scary deal,” says Bart Parker, whose ranch is located next to the reservation. “The amount of water they filed for was astronomical. Way more than the state engineer said was here.” He and other ranchers feared if the tribe got the extension, the resultant pumping would dry the springs out on some of the farms.

In 2009, the Utah State Engineer denied the application, in part because “it would impair the water rights of others.” The tribe, however, successfully requested the department reconsider its application, and are invited to submit a less ambitious water request.

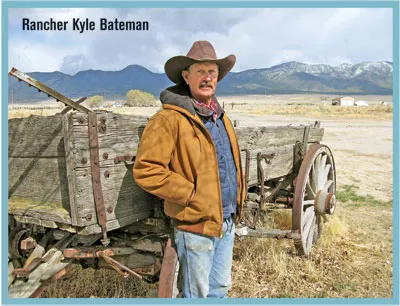

Despite such disagreements, the ranchers view the tribe as the best bet they have to keep Nevada at bay. “They have a lot more influence than we will ever have,” says rancher Kyle Bateman.

Justin Parker, Bart’s brother, opened a general store a mile down the road from Bart’s ranch last fall. Sitting in a rocking chair in his store, he says, “We’re already starving for water, it’s a pretty precious commodity. But if you’re going to live in the desert, you can’t bitch about it. But you don’t want to see less of it.”

Even a little pumping could be disastrous, Bateman says. “Our annual rainfall is 8 to 11 inches. [Nevada] said it would only draw down x amount of feet. That doesn’t mean anything to me. Inches would really have a negative effect on our economy. It would dry us up.”

Bart Parker looks out the window at the snow-capped Deep Creek Mountains, as the wind trembles plants on his porch. “It’s special to me as an individual. There’s nothing like home, especially when it encompasses thousands of acres, the whole valley and the next valley where I grew up. I consider this whole area to be home. And it’s certainly worth fighting for.”

GROWING PAINS

On March 22, 2010—World Water Day—150 people trudged up through mud for half an hour from the southern end of the reservation to Nelms pond, Marilyn Linares recalls, to bless the water. As the sun came up, they gathered around Naranjo and a tribal elder, who performed a ceremony, said a prayer, and then they drank the water. “It got real quiet,” Linares says. “I felt moved.”

Two years later to the day, Nevada State Engineer Jason King made his ruling on the pumping of the rural Nevada valleys. The state granted the water authority permission to pump up to 84,000 acre-feet of groundwater each year from four rural valleys. King ordered that Spring Valley be pumped in stages rather than full bore, to assess the potential environmental impact.

Rancher Bart Parker expresses disdain for the idea that SNWA would stop pumping if it proved damaging. “They’re not going to shut the pump off because the Parkers are experiencing abnormally dry conditions,” he says.

SNWA’s Davis says, though, that the fear that “once we begin pumping no force on heaven or earth can make us stop, that’s just not true.” The water rights granted by the Nevada State Engineer “are not a blind check.”

Just within the 30-day filing period, the Goshutes, the Ely Shoshone Tribe and Duckwater Shoshone Tribe lodged an appeal in Nevada’s 7th Judicial District Court.

Greymountain says SNWA “still answers ‘I don’t know’ to certain questions,” such as how long do they plan to pump. “They tell us we’ll not be affected. I know they’re wrong. I see they’re wrong. In my mind we have to keep fighting it, there really is no room for negotiation.” SNWA, she feels, is focused only on Las Vegas’ immediate need for water.

One wildcard is the BLM, which is expected to announce a decision later this year, after seven years of study, on whether or not it will permit the pipeline project across public land. But council members have little faith that the BLM will stand up for them.

Naranjo’s frustration and anguish is evident in his words and gaze. “We’ve got to send a message, to be sincere. If we have to stand up physically and stop something, like lay in front a bulldozer, then we’ve got to. They’ll continue to run us over if we don’t.”

THE SONG OF THE WATER

Steele puts his box of feathers into his truck and drives to the southern end of the reservation—“the upper rez” as residents call it. He parks by a stream whose waters churn with ice melt. Here are the willow trees from which tribal women cut shoots to make a baby’s cradle. “They use their teeth to pull off layers of bark,” Steele says. The cradle-makers choose the red branches in particular, as they are the strongest ones, “so the baby can absorb the strength.”

Under a tree he unexpectedly finds the remains of a hawk’s tail, feathers he had long been searching for. “My heart grew real big inside of me” at what he calls “a gift from the Creator. It made me feel strong.” He plans to make the feathers “beautiful, then pass them down in ceremonies to my grandkids.”

He sings a ceremonial song to the water. The song includes words in English for those who attend ceremonies who don’t speak Goshute. “Let’s go to the creek and get some water,” he sings in Goshute. Then in English, “I pray for you, I sing for you, happy birthday to you.”

Through the water, he says, he connects with the spirits, using their power to reach the people he is trying to protect. The thought that Las Vegas may take this water fills him with sadness.

“It would take away an important part of my wholeness,” he says. “The rocks, the trees, the grass will be sad, we will be sad. It will be a sad ending to the Goshute tribe, a sad legacy for all these decision makers, without much thought of the environmental racism and destruction that will happen. It paints a very bleak picture going into the future.”

With the BLM expected to release its environmental-impact study later this year, the SNWA anticipates ongoing litigation from opponents of the project. So it will “continue to trudge through the permitting process,” Davis says, until it can reach “shovel-ready status.” But it will be the Colorado River and Lake Mead’s dropping elevations that will trigger the start of pipeline construction, he says.

Steele drives up into the Deep Creek range, stopping to watch a herd of elk climb the mountainside as an eagle circles overhead. Steele continues up to the source of several springs. It’s a crag of rock from which warm water, home to rare Bonneville cutthroat trout, comes up from aquifers miles below. This is the water he uses for his sacred ceremonies. “Good water, 99.9 percent pure,” he says. It’s also the water that will be the first to go when the pumps get switched on, he fears.

CLIFF EDGE

This primal spring erupting from ancient rock has been the site of so many sacred songs by other tribal members, other tribes over the centuries, Steele says as snow begins to fall. They drink this water, they sing to it and it carries their songs and the spirits down the stream, down the valley.

He squats down by the moss-lined stream, the stream echoing past him. He is somber and still, as if in prayer.

What troubles him, he says, is how to tell the youth, and particularly the schoolchildren at Ibapah’s elementary school, about what the pipeline means 75 years from when the pumping starts. That’s when the reservation will see an impact, he fears, when the water disappears.

“I don’t feel the light bulb has turned on for them,” he says. “How do I approach them to tell this bleak story? It’s like sending them out into the dark without a flashlight. You tell them there’s a cliff out there somewhere, but they still fall to their deaths.”

Long after he has gone, he says, and joined the spirits of his ancestors in their sacred water, the children and their children will inherit the consequences of the SNWA’s initiative, of the failure of federal agencies, and finally the tribe itself, to protect their most precious natural resource. “There’s no way around it,” he says. “They can’t run and hide.”

| LANGUAGE RIGHTS The future of water isn’t the only issue that perplexes the Goshute. Their language is also at a crossroads, particularly in terms of passing it on to the elementary school’s 20 students. For the past few years, Ruby Ridesatthedoor has taught Goshute to the children. She first starting speaking Goshute to children at picnics, but none of them understood her. “Hardly anybody speaks Indian,” she says. The children prepared a book of their sayings about the water in English, which the elders translated into Goshute, albeit with some difficulty, as some English words lack equivalents in Goshute.

Linares had the children draw and cut out a 92-inch diameter circle, similar to the size of the pipes that will pump water to Las Vegas. Her students lay in the 7.6-foot outline and drew around their bodies before sticking the paper up on the wall. “They were all quite flabbergasted” at the size of it, Linares says. While Marty Pete fears, “Las Vegas will take all our water, instead of leaving some,” Tatyana adds that people are angry at Las Vegas, “because all of us are supposed to have our own water. They have their own. We have ours. Our language is with the water.” But Ridesatthedoor is shortly moving to another state. “No one else has stepped forward to take up the program,” Linares says. Much like losing the water, the loss of their language seems a dire prospect for the tribe. “Then we can’t talk to our ancestors,” Steele says. |